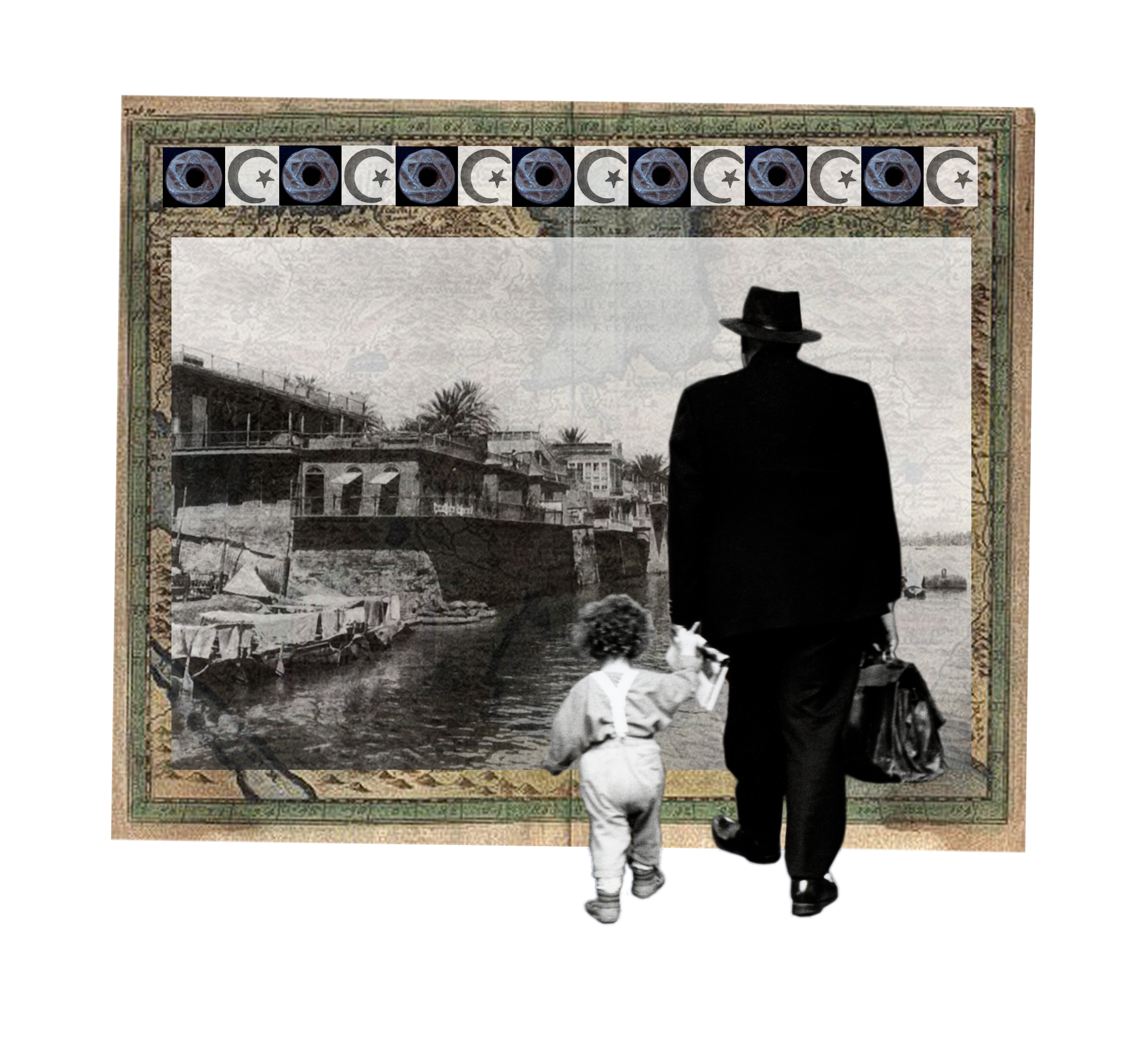

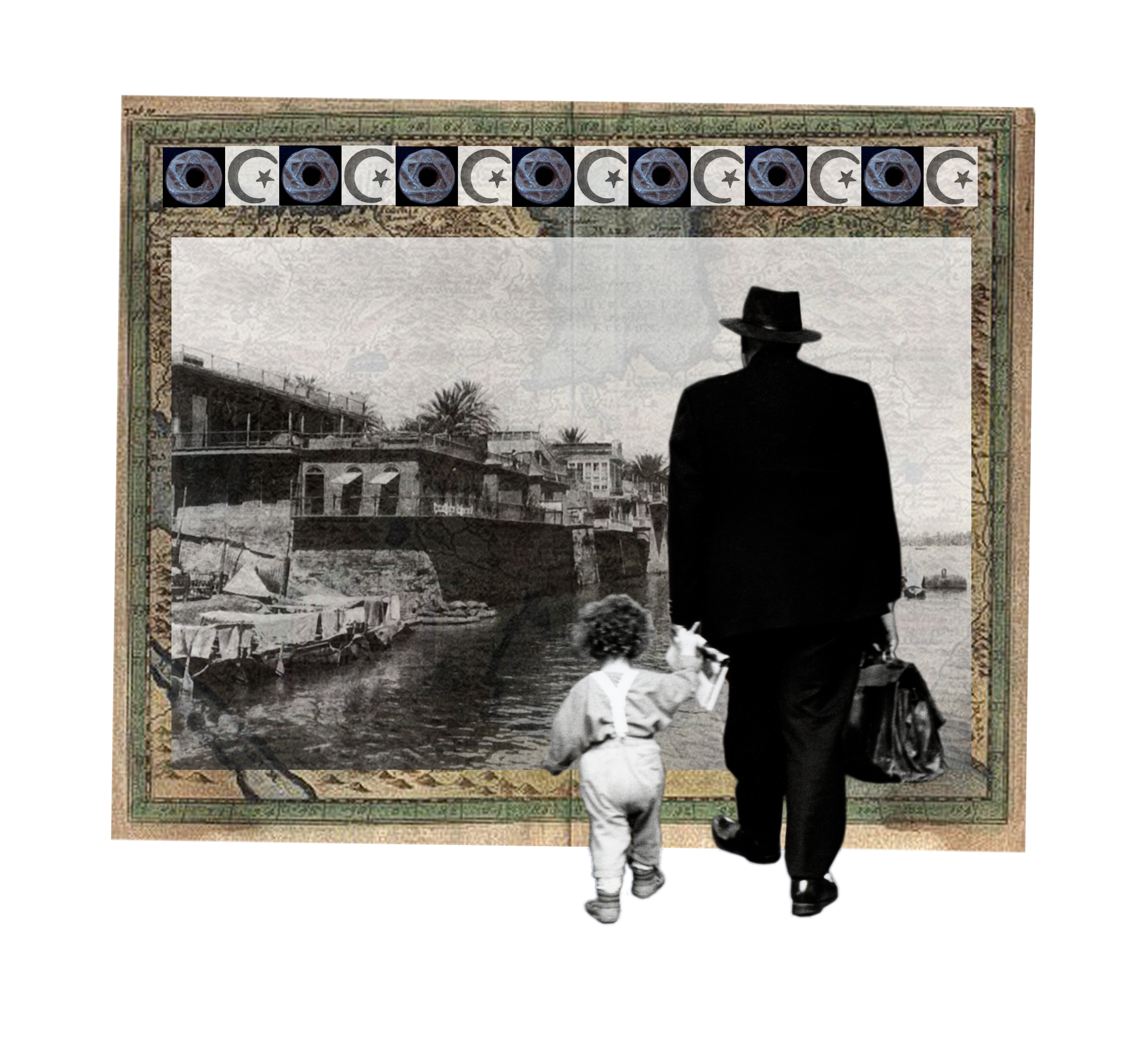

Here are excerpts of Iraq's Last Jews in Arabic (here is the the cover of book as photographed in an Iraqi bookstore ), here in German: Iraks letzte Juden. and in Hebrew.

Some 2,500 years after the first Jews established roots in Babylon, the once-vibrant and prosperous Jewish community of Iraq has disappeared. A community that numbered close to 140,000 in the late 1940 and comprised fully one-third of Baghdad s population consisted of a mere 20 when U.S. tanks rolled into the Iraqi capital in 2003.

Yet as late as the 1920s and 1930s, Iraqi Jews felt the heady potential of full equality in a secular society for the first time in their long history of subordination to Muslim rulers. From music to politics to commerce, Jews played a major role in Iraqi society and culture. For centuries after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, Babylon was the world s epicenter of Jewish life and religion the place where the Babylonian Talmud was written and where rabbis from across the region and Europe came to learn from the most scholarly sages. But the community dissolved in the middle of the 20th century when pro-Nazi forces, Arab nationalism, and the formation of Israel led to violence against and a general sense of insecurity among Iraqi Jews, causing them to flee, mostly over the course of about a year and a half.

This book tells the story of that last generation, people who in many cases grew up with strong patriotic feelings but were always prepared for a future beyond Iraq's borders just in case. The storytellers of these first-person accounts vary as widely as any group of Jews does, reflecting the breadth and texture of the community: wealthy businessmen and Communists, popular musicians and reformist writers, Iraqi patriots and early Zionists. Many had close friends among the Muslims and Christians of Iraq of whom they speak warmly. They tell the tales of a people with a love for their birth country that persisted even as they were forced to leave their homes.

The story of the final decades of the Jewish community in Iraq divides into three periods. First is the period before 1939 when the Jews in Iraq saw themselves as part of the Iraqi national fiber in government, commerce, and the arts. That ended verbally with the rise of Nazi influences andviolently with the Farhoud, a pogrom against the Jews, in 1941. Second is the period between then and 1953 when increasing Nazi agitation and Arab hostility toward the new state of Israel turned most Jews into Zionists and the vast majority of the community left. The final period records an Iraq that drifted towards increasingly autocratic leadership, culminating in the sadistic dictatorship of Saddam Hussein, with the Jews often playing the role of scapegoat. Finally, the book closes with several moving retrospectives of the community from a diverse group that includes two poets, a novelist, and an Iraqi Shiite.

These stories are sometimes funny, often tragic, touching, and insightful. Readers will find that the editors, in addition to recording descriptions of daily life, have also uncovered acts of heroism, adventure, and intrigue: from the undercover Israeli agents who helped orchestrate the mass emigration of Iraqi Jews to the young Jewish state at mid-century, to those who argued for the lives of their loved ones in the brutal prisons of Saddam Hussein. What has been compiled here, ultimately, is a book about quiet bravery in times of distress and a celebration of the possibility of peace.

Finalist, National Jewish Book Award 2008, Sephardic Culture

Interview January 19, 2008 on the BBC. Please note that it may take 30 seconds to load depending on your connection speed.

Interview on WKGO. Look at the 5 AM slot.

A review in Choice .

A review in the New York Post can be found here and is reproduced below.

A review in the Jewish Journal of Boston can be found in the 1800s and 1900s.

A review by the deputy director-general of the Israeli Foreign Ministry is reproduced below.

A review in the Jewish Book World is here

The cover of the magazine Masaaraat in which the introduction to our book (written by Dr. Shmuel Moreh) is translated to Arabic.

There are several reviews of the German translation further down on this web page.

By MICHAEL SOUSSAN November 23, 2008

"I felt I was leaving behind the Garden of Eden," writes Oded Halahmy of his expulsion from Iraq. His is just one of the fascinating testimonials in "Iraq's Last Jews," a compilation of first hand accounts by Jews who fled their Iraqi homeland. These stories provide more than just the details of Iraq's former Jewish community; we learn so much about that country's larger history and culture.

At the time of the British occupation of Iraq in 1917, one third of Baghdad's population was Jewish. An incredible statistic, given that there are only about a dozen Iraqi Jews left there today. Of the 137,000 Jews who resided in Iraq in the early 1940s, 124,000 had fled the country by 1952.

The book is filled with amazing characters like Baghdad-born Halahmy, who moved to Israel in 1951, and is now a famous sculptor and art gallery owner in New York. At his Pomegranate Gallery in SoHo, Halahmy now helps young Iraqi artists (of all faiths) promote their work internationally.

In contrast to his positive memory of Iraq, Linda Masri Hakim, who left in 1972, after the Ba'athist regime had taken power and steadily increased its persecution the Jewish community, still has nightmares about being stuck in that country today. "When I wake up, I touch my pillow and say, 'thank God I am not in Iraq.'" Linda says she would like to "close the book" on the Jews' history in that country and "forget about perpetuating the memory. This is my attitude because we can't go back in the same way that European Jews could go back to Europe after the Holocaust."

From the mix of idyllic and traumatic memories we get a sense of the enormous loss Iraq itself suffered from the persecution and flight of its Jewish community. Shiite Muslim Dhiaa Kasim Kashi writes that, from a cultural standpoint, Iraq "suffered a big shock when the Jews left," because "all of Iraq's famous musicians and composers were Jewish," as were a large portion of its other artists. In addition, "Jews were so central to commercial life in Iraq that business across the country used to shut down on Saturdays because it was the Jewish Shabbat. They were the most prominent members of every elite profession - bankers, doctors, lawyers, professors, engineers, etc." In Kashi's view, had the Jews stayed, they would have helped "manage the country far better" and served as a "moderating influence of society," a bulwark against the "extreme brand of Arab Nationalism" embodied by Saddam Hussein, which ultimately led the country into three devastating wars and complete economic collapse.

If many of the individuals who fled Iraq rose to prominence thereafter, it may be due to the exceptional richness of their heritage. They were thoroughly integrated into the larger community and used Arabic as their main language, they were literate and Jewish community leaders played an important role in shaping Iraq's political destiny for centuries. Sir Sassoon Hezkel, for example, participated in the negotiations with Winston Churchill that led the formation of the modern Iraqi state. Knighted by the British crown, he was also an early supporter of King Faisal I, the first Hashemite leader of Iraq. (He later served as Faisal's minister of finance, which goes to show the level of trust that used to exist between Iraq's Muslim and Jewish communities).

Yet "Iraq's Last Jews" is almost a misleading title. The story of Iraq's prominent Christian communities is also told here. At a time when many Iraqi Christians are suffering from renewed persecution, their proud history is both timely and relevant for diplomats and journalists involved in that country's transition. It is not a coincidence, for example, that the northern city of Mosul remains the last bastion of Sunni extremism. There is a very real fear among some of the town's Sunni population, many of whom now live in the homes formerly occupied by expelled Jews, Kurds and Christians, that they may be dispossessed of the ill-gotten gains they acquired under Saddam's rule.

What is it about this ancient land that had the world's major powers involved in its destiny throughout recorded history? That is the larger question this book addresses. The testimonies of "Iraq's Last Jews" serve as the narrative threads that help to unveil layer upon layer of false assumptions and misguided perceptions, most of which stem from news coverage devoid of historical perspective. Even the normally well-informed New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman thought it wise to joke, in 2003, that the US had invaded "the Flintstones." Though Friedman was obviously trying to convey the extreme poverty he witnessed while traveling through Iraq, of all the countries the US has ever invaded, Iraq may be the least befitting of such a simplistic analogy. Iraq is a naturally rich country, both in resources and culture, and the extreme poverty its civilians were reduced to under Saddam Hussein is a historical anomaly.

"Iraq's Last Jews" does describe heart wrenching tragedies, but the collection also reminds us that "mutual respect and even friendship" between Arabs and Jews and Christians was "once the norm" in Iraq.

Having traveled extensively throughout Iraq, both before the war (as a humanitarian worker) and after the 2003 invasion (as a journalist), I learned more flipping through these 200 hundred pages than I imagined possible. "Iraq's Last Jews" is without a doubt the most surprising and informative book about that country's culture and history to date.

Michael Soussan teaches international relations at New York university's Center for Global Affairs and is the author of the book Backstabbing for Beginners: My crash course in international diplomacy.

Book Sheds Light on Iraq's Once-Thriving Jewish Population Eric Shoag Special to the Journal Wed, January 28, 2009

Iraq's Last Jews: Stories of Daily Life, Upheaval, and Escape from Modern Babylon Tamar Morad, Dennos Shasha and Robert Shasha Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

When one thinks of Iraq, images of war, destruction and chaos come to mind. One certainly does not imagine it being home to a flourishing, vibrant and vital Jewish community.

Yet in the not- too-distant past, that is precisely what existed there, and the largely untold story of that community and its demise is the subject of the book "Iraq's Last Jews: Stories of Daily Life, Upheaval, and Escape from Modern Babylon". The book is part of Palgrave Macmillan's "Studies in Oral History" series. The story is by no means a pleasant one, but it is essential to our understanding of not only the past and present of Iraq, but also of Israel, and of the epic Jewish odyssey of the tumultuous twentieth century.

At just over two hundred pages, this unassuming volume is packed with the detailed reminiscences of ex-patriots from many different social and economic strata. Editors Tamar Morad, Dennos Shasha and Robert Shasha have trimmed the narratives skillfully to present a composite picture of a once-thriving community systematically decimated over the years by the whims of unstable governments, and the fanned flames of racism and Arab nationalism.

Many of the interviews begin with affectionate recollections of a beloved homeland lost forever: the sights, sounds, and smells of routines, relatives, friends and neighborhoods now dispersed and dismantled. Jews were an integral part of Iraqi society from the centuries it existed as part of the Ottoman Empire, through the British-Arab alliance following World War I that resulted in its creation as an independent state. King Faisal's benevolent rule over this new state fostered an atmosphere of tolerance and equality which ended abruptly with his death in 1933, after which rising anti-Jewish and Pan-Arabic sentiment led to restrictions on all phases of Jewish life, culminating in the establishment of a pro-Nazi government and a notorious deadly pogrom against the Jews known as the Farhoud in 1941.

Anti-Jewish feelings exploded to new heights in the aftermath of Israel's independence in 1948, and its subsequent victory over the Arab armies that challenged its very right to exist. This led directly to the massive emigration of Jews from Iraq to Israel in the 1950s in what came to be called Operation Ezra and Nehemiah. It is here that a book of this kind, a history told in the form of a string of first-person tales, is particularly affecting. The notion that history is made up of ordinary people's decisions is brought home in full force, particularly in the story of Shlomo Hillel, an agent of the Mossad (Israeli Secret Service) who helped organize illegal airlifts of Jews. Hillel tells of the moment of panic he experienced when he found himself in a cockpit for the first time, feeling completely in over his head, fearing imminent discovery and failure. The individual leaps of faith by people like Hillel added up to a heroic movement whereby most of Iraq's 140,000 Jews found new homes in Israel and elsewhere.

Things turn surreal and horrific in the testimonies of those who stayed in Iraq through the 1960s, when the cycle of tolerance supplanted by increasingly repressive regimes continued, leading to the domination of the sadistic Saddam Hussein, who appears in these pages in some truly foreboding and ominous encounters. Random arrests and torture became commonplace, especially after Israel's decisive victory in the Six-Day War of 1967, when Jews suddenly found themselves without jobs, their assets frozen, and even their phone service cut off.

A brutal touchstone moment came in January 1969, when a group of 15 prisoners (nine Jews) was hanged in the public square of Baghdad. This event, like the Farhoud of 1941, we see through many pairs of eyes, including those of Zuhair Sassoon, grandson of the last Chief Rabbi of Iraq, whose father was imprisoned with those who were hanged. Sassoon speaks of his shock upon seeing the bodies and identifying his father's distinctive shoes on one of them. After what "felt like an eternity," he looked up to the face, which was that of a stranger. His father (released the following year) had loaned the shoes to another, less fortunate, prisoner.

Sadly, Jews themselves are not spared criticism from some interviewees, who tell of Israeli prejudices against Arab Jews, or Mizrachim, once they arrived in the Jewish State. The difficulties Mizrachim faced both in Iraq and at the hands of a largely Eastern European, or Ashkenazi, power structure in Israel is perhaps understandably avoided considering the unflattering light it shines on traditional Zionist narratives, but it should not be ignored. The once-voluminous Jewish population of Iraq has dwindled incredibly to the single digits, but thanks to this book, its story has not disappeared and the small but significant acts of kindness and heroism that punctuate this tragic tale lend it an air of humanity and hope, as well as the fact that by its mere existence, there is the opportunity to learn from the mistakes of the past and forge a brighter future both for the Jews and for the world at large.

Eric Shoag writes from Boston

Here is how it appeared originally in the Jerusalem Post: first page and second page

May 27, 2009 12:18 | Updated May 28, 2009 12:41

Babylonian heritage

By ZVI GABAY

Iraq's Last Jews - Stories of Daily Life,

Upheaval and Escape from Modern Babylon

Edited by Tamar Morad, Dennis Shasha and Robert Shasha

Introduction by Prof. Shmuel Moreh

Palgrave-Macmillan

211 pp., $75.99 (hardcover)

Although the Jewish community of Iraq was forced to flee, its story is rarely told, leaving the Palestinians as the only victims of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

How does one explain the reason why a prosperous community of 140,000 people, with a history and heritage of 2,600 years, uproots itself en masse, and leaves Iraq, the country which it helped modernize in all areas - government and politics, economy, medicine, education, literature, poetry and music? An explanation for this extraordinary historical phenomenon is found in Iraq's Last Jews.

This book includes testimonies of 19 Jews (men and women) as well as of an Iraqi Shi'ite, who personally experienced the events that occurred in Iraq during the last century.

The main reasons that brought about the escape of the Jews from Iraq may be summarized as follows:

the xenophobia of the nationalistic Sunni leadership, which did not tolerate minorities, including Shi'ites, Christians and Kurds, especially if they had substantial financial means and social standing;

anti-Semitism, which existed in newly independent Iraq (and in other Arab countries), which was sponsored by Nazi Germany and led by the German ambassador, Dr. Fritz Grobba, who was supported by fanatical religious leaders, such as Haj Amin el-Husseni (who escaped from Palestine under British Mandate and continued his anti-Jewish activities in Iraq).

The climax of the anti-Jewish activities in Iraq, was the Farhud - the uprising against the Jews on Shavuot of 1941 - during which 135 men, women and children were murdered, hundreds were injured and much property was looted. This uprising ultimately brought about the escape and the mass emigration of the Jews from Iraq. The longing for Zion among Iraqi Jews directed many of them to Mandate Palestine and later on to Israel, while a minority opted to immigrate to other countries such as the United States, Canada, England and Australia. Today, the number of Iraqi Jews residing in Israel is 244,000, while 40,000 are distributed elsewhere in the world.

The catastrophe of the Jews of Iraq occurred for no obvious reason. The anti-Jewish policy of its governments left them with one option - to escape and leave behind all their personal and communal property. Unlike the Palestinians, the Jews of Iraq did not wage a war against Iraq nor did the Jews in other Arab countries. They were the scapegoats of political conflict in their own countries. Israeli governments throughout the years, for reasons which are not clear, did not include this catastrophe of the Jews of Arab countries as part of their political agenda nor was it included in the educational program, as in the case of the Nakba of the Palestinians. This enabled Arab propagandists to portray the Palestinians as the only victims of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

The testimonies are personal and include a broad description of Jewish life in Iraq spanning the comfortable day-to-day life, mainly during British rule, the sufferings and persecutions once Iraq became independent and finally the escape to Eretz Yisrael, through the assistance of the Zionist underground movement, which was established after the Farhud.

They are also authentic and can be the basis for writing the history of the Jews of Iraq in the last century. The introduction, written by Prof. Shmuel Moreh, provides historical background and explains how the Jewish community survived for 2,600 years, in Babylon and later in Iraq.

The extraordinary history of Dhiaa Kassem Kashi, the young Shi'ite, who suffered from oppression in Iraq and was forced to escape in the 1980s, is a vivid example of the sufferings of the non-Sunni communities in the country. He longs for the good relations that existed between his family and his Jewish neighbors. Needless to say, there were Muslims who did not agree with the policy of hatred toward the Jews; however, their voices at the time were not heard. The Jews in Iraq suffered from the struggles between the Sunnis and Shi'ites, as today Israel is at the center of the conflict between Shi'ite Iran and Sunni Arab countries.

The timing of the publication of this book is critical, since firsthand testimonies of Jews who lived in Iraq are dwindling (two of the Jews included in the book were not fortunate enough to see its publication). In this respect, special acknowledgment should be given to the Jewish Babylonian Heritage Center in Or Yehuda, for its important work in collecting and documenting personal testimonies of Iraqi Jews.

Since the book is in English, it provides for the first time a good glimpse of the history and the plight of the Iraqi Jewish community to a broad range of readers. Many of the descendents of the Jews of Iraq in Israel and other countries reached prominent positions in a range of fields - government, economy, science and the arts - due in part to their great heritage. The book is highly recommended for readers interested in exploring this unfortunately neglected part of Jewish history.

The writer is a former ambassador and deputy director-general of the Foreign Ministry.

Deutschlandradio Kultur Erinnerungen an die einst bluehende juedische Kultur im Irak August 23, 2012

Audio review of Dr. Catherine Newmark was recorded using garageband and can be found here.

Die fuer dieses Buch zusammengetragenen Zeitzeugeninterviews geben einen wunderbaren Einblick in die Geschichte der irakischen Juden im 20. Jahrhundert. Den Gespraechstexten sind hilfreiche kurze historische Einleitungen vorangestellt. Seit dem babylonischen Exil vor rund 2.500 Jahren leben Juden im Irak, Ueber Jahrhunderte war die dortige Gemeinde eine der wichtigsten. Um 1940 zaehlte sie mehr als 130.000 Menschen und machte ein Drittel der Bevoelkerung Bagdads aus, Juden waren wichtige Stuetzen der irakischen Gesellschaft.

Mit den Unabhaengigkeitskaempfen des Irak von der Mandatsmacht Grossbritannien, dem arabischen Nationalismus und dem Einfluss des Nationalsozialismus verstaerkte sich ab den 1930ern der Antisemitismus; 1941 kam es zum sogenannten "Farhoud", einem zweitaegigen Pogrom, bei dem 170 Juden getoetet und viele verletzt wurden. In der Folge dieser Ereignisse sowie auch des Zionismus und des nach der Staatsgruendung Israels 1948 verschaerften juedisch-arabischen Konflikts begannen Juden, aus dem Irak zu fliehen. Von 1950 bis 1951 verliessen in einem Massenexodus mehr als 120.000 Juden das Land in Richtung Israel. Heute leben nur noch weniger als ein Dutzend Juden im Irak.

Die Geschichte der orientalischen Juden ist im Okzident wenig bekannt, und auch in Israel waren die Misrachim, die Juden aus den arabischen Laendern, lange eine kulturelle Minderheit, die von der aschkenasischen Mehrheitsgesellschaft wenig Beachtung und manchmal auch Verachtung erfuhr. Im juedisch-arabischen Konflikt, in dem sie aufgrund ihrer "arabischen" Herkunft auch haetten vermitteln koennen, gerieten sie oft zwischen alle Fronten.

Das Buch "Iraks letzte Juden" gibt nun einen wunderbaren Einblick in die Geschichte der irakischen Juden im 20. Jahrhundert. Es besteht aus Interviews mit bedeutenden Zeitzeugen, die durch hilfreiche kurze historische Einleitungen eingefuehrt werden. Den Anfang machen Erinnerungen an die Zeit vor dem Exil, an die widerspruechliche Existenz als Minderheit in einem arabischen Land zwischen Eingebundenheit und Diskriminierung, und die Bedeutung, die die juedische Gemeinde fuer das Land hatte.

So erfaehrt man, dass fast die gesamte irakische Musikszene in juedischer Hand war (das 1936 gegruendet "Iraqi Broadcasting Authority Orchestra" war bis auf einen einzigen Musiker ausschliesslich juedisch besetzt) und dass auch heute noch fast alle traditionelle irakische Musik von juedischen Komponisten stammt.

Ein weiteres Kapitel ist der Flucht und Vertreibung gewidmet, wichtige Figuren wie Shlomo Hillel und Mordechai Ben Porat, welche federfuehrend die Luftbruecke organisierten, mit der in tausend Fluegen die Juden Anfang der 1950er Jahre den Irak verliessen, kommen zu Wort, sie erzaehlen von den dramatischen und hoechst improvisierten Verhandlungen und Geheimdienstaktivitaeten, mit denen dies ermoeglicht wurde.

Auch die Schwierigkeiten der Fluechtlingsmassen, in Israel ganz neu zu beginnen, werden geschildert, und zuletzt erfaehrt man auch vom Leben der wenigen im Irak verbliebenen Juden, die nach dem Sechstagekrieg 1967 schwersten Verfolgungen ausgesetzt waren und ab 1979, wie andere Minderheiten auch, ganz besonders unter der Schreckensherrschaft von Saddam Hussein litten.

Mit ihrer Fuelle von faszinierenden Details (so liest man, wie die Ehefrau eines verhafteten Juden mehrfach bis zu Saddam Hussein persoenlich vordringt, der sie im Hausrock empfaengt) bilden die vielen persoenlichen Erinnerungen in ihrer Gesamtheit eine unglaublich dichte und spannende Geschichte des Irak im 20. Jahrhundert, aus der Sicht einer seiner Minderheiten. Eine Minderheit, die auch mehr als ein halbes Jahrhundert nach ihrem Exil noch Sehnsucht nach ihrer alten Heimat empfindet - auch dies ein anruehrender Aspekt, der aus vielen Erzaehlungen deutlich wird.

Besprochen von Catherine Newmark

Tamar Morad, Dennis und Robert Shasha (Hg.): Iraks letzte Juden - Erinnerungen an Alltag, Wandel und Flucht Aus dem Englischen von Anke Irmscher Wallstein Verlag, Goettingen 2012 320 Seite, 24,90 Euro

... Die Herausgeber lassen gefuehlvoll, eindruecklich und sehr persoenlich irakischstaemmige Juden, von Bankern, ueber Schriftsteller bis hin zu Kuenstlern,... Das Buch ist Plaedoyer fuer den frienden, denn die im Irak lebenden Juden waren es die erfahren waren... Sie lassen den Leser teilhaben an traditionellen Festen, ihrer Liebe zur irakischen folklore und Musik, ihrer Sehnsucht dorthin und auch an ihrem erfahrenen Schmerz.

Ein Gespraechs- und Interviewband laedt ein, die kaum bekannte Geschichte des Judentums im Irak zu entdecken. Von Alexander Kluy

Das Buch Iraks letzte Juden ist ein wichtiges, ein bewegendes Memorial. Und ein eminentes Zeugnis. Es ist eine archaeologische Erinnerung an eine Zeit, als jeder dritte Einwohner Bagdads Jude war (1917: 202.000 Einwohner -- davon knapp 80.000 Juden); und es ist Erinnerung an eine der am laengsten existierenden Gemeinden.

Ungefaehr 2.500 Jahre lang gab es eine juedische Gemeinschaft in Babylon, in Mesopotamien, im Irak. Lange waren sie, worauf Shmuueel Moreh in seiner klugen, konzisen Einleitung verweist, politisch, wirtschaftlich und gesellschaftlich gut integriert. Bis zum abrupten Exodus im Jahr 1950, als buchstaeblich ueber Nacht im Zuge der Operation Esra und Nehemia rund 124.000 der 137.000 irakischen Juden nach Israel uebersiedelten.

...

Das nicht zuletzt gut uebersetzte und sorgfaeltig edierte Buch inklusive Zeittafel und weiterfaehrender Literatur ist ein bewegendes, Augen oeffnendes und nicht hoch genug zu lobendes Memorial. Aehnliches wuenscht man sich ueber viele andere Diasporagemeinden.

December 8, 2012

http://www.welt.de/print/die_welt/literatur/article111892900/Iraks-letzte-Juden.html

Iraks letzte Juden Bagdad war eines der wichtigsten sephardischen Zentren. Heute sind die Ueberlebenden traurige Zeugen einer vergangenen Epoche Von Najem Wali

Mehr als 2500 Jahre lang haben Juden im Irak gelebt. Trotz Unterdrueckung, politischer Unruhen, Krieg und Plagen, war die juedische Gemeinde in der Lage, ihre Identitaet, Kultur und Tradition zu bewahren. Gleichwohl waren sie politisch, sozial und oekonomisch gut im Lande integriert, und durch ihre Sprache, ihre gesellschaftlichen Traditionen und ihrer Lebensweise im Wesentlichen kaum von ihren arabischen Landsleuten zu unterscheiden. Es war eine pulsierende und bluehende Gemeinde, deren Mitgliederzahl sich in den 1940er-Jahren noch auf etwa 150.000 Seelen belief (einer alten britischen Statistik zufolge sah die Verteilung folgendermassen aus: fuenf Prozent von ihnen waren reich, dreissig Prozent gehoerten der Mittelschicht an, sechzig Prozent waren arm, und fuenf Prozent waren Bettler). Allein in der irakischen Hauptstadt Bagdad zaehlte die juedische Gemeinde 130.000 Mitglieder und stellte damit ein Drittel der gesamten Bevoelkerung der Stadt. Als 2003 die amerikanischen Panzer in Bagdad einrollten, bestand die juedische Gemeinde gerade noch aus 20 Personen!

Bis zu ihrem Massenexodus im Jahre 1951 betrachteten die Juden sich selbst als Teil des Iraks und seiner Geschichte. Sie waren stolz darauf, die Erben einer grossartigen, in kultureller und geistiger Hinsicht einzigartigen Vergangenheit zu sein. Der babylonische Talmud oder auf Hebraeisch das "Zeitalter der Dscha'unim" oder "Zeitalter der Genies", bezeichnet diese vergangene Epoche, als die, in der die grossen Rabbiner und Denker aus ihren Reihen hervorgingen.

Es ist also nicht verwunderlich, wenn die irakischen Juden sich automatisch als an dem "modernen", im Jahr 1921 gegruendeten irakischen Staat interessierte Mitbuerger betrachteten. Zum ersten Mal in ihrer langen Geschichte unter muslimischer Herrschaft machten die Juden die Erfahrung, gleichberechtigt in einer saekularen Gesellschaft zu leben. Ab jetzt spielten sie eine herausragende Rolle in der irakischen Gesellschaft -- in der Musik, der Politik, bei Technik und im Handel. Auch der erste Finanzminister in der Regierung von Koenig Faisal, Sassoon Eskell, war Jude.

Leider war diese Euphorie, diese goldene Aera nicht von langer Dauer. Die aelteste Gemeinde im Irak musste erleben, wie Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts nazifreundliche Stroemungen, arabischer Nationalismus und die Gruendung des Staates Israels zu Gewalttaetigkeiten gegenueber irakischen Juden und zu einem allgemeinen Gefuehl der Unsicherheit unter ihnen fuehrten. Am 6. Mai 1941 fand der Farhud (irakisches Pogrom) statt, zwei gesetzlose Tage nach der Niederschlagung eines Militaerputsches unter der Fuehrung von Kolonel Raschid Ali al-Gailani, einem Freund von Hitler, der spaeter nach seiner Flucht in Berlin vom "Fuehrer" persoenlich empfangen wurde. Ab diesem Tag flohen immer mehr Juden aus dem Land -- die meisten im Verlauf von nur anderthalb Jahren.

Es ist erstaunlich, mit welcher Praezision alle interviewten aus dem Irak stammenden Juden in dem kuerzlich im Wallstein Verlag erschienenen Buch "Iraks letzten Juden", die Chronik vom Verschwinden der ältesten Gemeinde im Irak, von ihren tragischen, aber auch gluecklichen Momenten erzaehlen. Wir lesen von Menschen, "die nicht selten starke patriotische Gefuehle für ihr Land hegten, die sich aber immer für eine Zukunft ausserhalb der Landesgrenzen bereithielten, fuer alle Faelle." Da die Ich-Erzaehler, "die im Buch zu Wort kommen, so wenig homogen sind, wie jede andere Gruppe von Juden auch", sind deren Geschichten in drei Kategorien eingeteilt: Unter dem Titel, "Der Irak, unser Land", erzaehlen Menschen von ihrer Überzeugung, dass sie (oder ihre Eltern) dachten, im Irak in "ihrem" Land zu leben. Unter dem Titel "Das Wagnis" berichten andere von ihren Leistungen als Pioniere der Zionistischen Bewegung in Bagdad oder auch als Agenten fuer den israelischen Geheimdienst, dem die Organisation des damaligen Massenexodus der irakischen Juden (1946-1951) zugeschrieben wird. Im Kapitel "Nicht laenger unser Land" versammeln sich jene Erzaehler, die von ihrem Beharren auf das Bleiben im Irak berichten, trotz Schikanen und Verfolgungen. Die letzten von ihnen verliessen den Irak erst 1982. All diese Lebenserzaehlungen offenbaren die Vielschichtigkeit der juedischen Gemeinde -- Geschaeftsleute und Kommunisten, bekannte Musiker und Schriftsteller, irakische Patrioten und fruehe Zionisten. Wir erfahren von Menschen, die im Irak oder spaeter in Israel, in den USA und Grossbritannien Geschichte geschrieben haben: Die Gebrueder Kuwaity, Salah und Daoud, zum Beispiel, die vielleicht beruehmtesten Musiker des Irak, die ihre Bluetezeit zwischen 1920 und 1940 hatten, und deren Lieder sich bis heute grousser Popularitaet in Irak und Kuwait erfreuen. Die Soehne von Khedouri Abdoudi Zilkha, der das erste Department-Bankensystem in der arabischen Welt gruendete, die Bank Zilkha, die 1951 in New York in Zilkha & Sohns unbenannt wurde. Shlomo Hillel, der fuenf Jahre lange -- ab 1946 -- Mossad-Agent war und die Organisation des Massenexodus der irakischen Juden geleitet hat. Richard Obadiah, der Sohn von Abdulla Obadiah, dem letzten Direktor der Frank-Iny-Schule, der letzten juedische Schule in Irak. Abdullah war bis die 1980er-Jahre einer der bekanntesten irakischen Mathematikprofessoren.

Unter seinen Studenten waren hohe Beamte mehrerer irakischer Regierungen, wie etwa der Saddams, oder der Leiter der nationalen Sicherheit in der Baath Partei, Nazim Kazzar. Von Letzterem, dem die Menschen spaeter den Spitznamen Jazzar, der Schlaechter, gaben, bekam Richard seinen Reisepass ausgehaendigt. Wir erfahren auch von den Kommunisten Salim Fatal und Sami Michael. Fatal wurde 1930 in Bagdad im armen juedischen Viertel Tatran geboren. Seiner Meinung nach sind Armut und Kommunismus die beiden verschwiegenen Kapitel der Geschichte der Juden. Sami Michael (1926 in Bagdad geboren), heute einer der populaersten israelischen Autoren, uebt sogar Kritik an den meisten Israelis, die ueber das Leben der Juden im Irak schreiben. Sie stellen die Realitaet so dar, schreibt Sami Michael, dass sie dem zionistischen Narrativ entspricht, in dem sie sagen, "dass die zionistische Deutung ihrer Auswanderung die einzig wahre sei". Fuer ihn ist das purer Mythos, denn "die irakischen Juden hatten eine aehnliche Einstellung zu Palaestina wie die Juden in Amerika heute: Das Wohlergehen der Juden in Palaestina war uns wichtig, aber wir lebten gerne in unserem Land und wollten es nicht verlassen".

Leider bedauern nur wenige Autoren im Buch wie Dhia Kachi, der 1952 in Bagdad geboren wurde, dass im Irak keine juedische Gemeinde mehr existiert: Aus zionistischer Sicht sollten ohnehin alle Juden in Israel leben; arabische Nationalisten sind auf Antisemitismus indoktriniert und viele Nachfahren der irakischen Juden wissen die der Gesellschaft, in die sie immigrierten, zu schaetzen. Trotzdem: "Die Geschichte der irakischen Juden ist mehr als die Flucht von Verfolgten vor dem Zugriff ihrer Verfolger".

The book is published by Palgrave Macmillan. So, if you are interested, you can either buy the book on an online website or contact the editors shasha@cs.nyu.edu, TMORAD@PARTNERS.ORG, or rshasha@cotswoldgroupinc.com.