Start Lecture #1

I start with chapter -1 so that when we get to chapter 1, the numbering will agree with the text.

There is a web site for the course. You can find it from my home page, which is http://cs.nyu.edu/~gottlieb

Start Lecture #1marker above can be thought of as

End Lecture #0.

The course text is Tanenbaum, "Modern Operating Systems", Forth

Edition (4e).

We will cover nearly all of the first six chapters, plus some

material from later chapters.

I once used a book by Finkel, which is now out of print, but is available on the web.

Replyto contribute to the current thread, but NOT to start another topic.

Grades are based on the labs and exams; the weighting will be

approximately

25%*LabAverage + 30%*MidtermExam + 45%*FinalExam

(but see homeworks below).

I use the upper left board for lab/homework assignments and announcements. I should never erase that board. Viewed as a file it is group readable (the group is those in the room), appendable by just me, and (re-)writable by no one. If you see me start to erase an announcement, let me know.

I try very hard to remember to write all announcements on the upper left board and I am normally successful. If, during class, you see that I have forgotten to record something, please let me know. HOWEVER, if I forgot and no one reminds me, the assignment has still been given.

I make a distinction between homeworks and labs.

Labs are

Homeworks are

Homeworks are numbered by the class in which they are assigned. So any homework given today is homework #1. Even if I do not give homework today, the homework assigned next class will be homework #2. Unless I explicitly state otherwise, all homeworks assignments can be found in the class notes. So the homework present in the notes for lecture #n is homework #n (even if I inadvertently forgot to write it to the upper left board).

You may develop (i.e., write and test) lab assignments on any system you wish, e.g., your laptop. However, ...

NYU Classes.

I feel it is important for CS majors to be familiar with basic

client-server computing (related to

cloud computing

) in which one develops on a client machine

(for us, most likely one's personal laptop), but runs on a remote

server (for us, i5.nyu.edu).

This requires three steps.

I have supposedly given you each an account on i5.nyu.edu, which takes care of step 1. Accessing i5 is different for different client (laptop) operating systems.

Good methods for obtaining help include

The department wishes to reinforce the knowledge of C learned in 201. As a result, lab #2 must be written in C. The other labs may be written in C or Java. C++ is permitted (and counts as C for lab2). However, C++ is a complicated language and I advise against using it unless you are already quite comfortable with the language.

Incomplete

The rules for incompletes and grade changes are set by the school and not the department or individual faculty member.

The rules set by CAS can be found in here. They state:

The grade of I (Incomplete) is a temporary grade that indicates that the student has, for good reason, not completed all of the course work but that there is the possibility that the student will eventually pass the course when all of the requirements have been completed. A student must ask the instructor for a grade of I, present documented evidence of illness or the equivalent, and clarify the remaining course requirements with the instructor.

The incomplete grade is not awarded automatically. It is not used when there is no possibility that the student will eventually pass the course. If the course work is not completed after the statutory time for making up incompletes has elapsed, the temporary grade of I shall become an F and will be computed in the student's grade point average.

All work missed in the fall term must be made up by the end of the following spring term. All work missed in the spring term or in a summer session must be made up by the end of the following fall term. Students who are out of attendance in the semester following the one in which the course was taken have one year to complete the work. Students should contact the College Advising Center for an Extension of Incomplete Form, which must be approved by the instructor. Extensions of these time limits are rarely granted.

Once a final (i.e., non-incomplete) grade has been submitted by the instructor and recorded on the transcript, the final grade cannot be changed by turning in additional course work.

This email from the assistant director, describes the departmental policy.

Dear faculty, The vast majority of our students comply with the department's academic integrity policies; see www.cs.nyu.edu/web/Academic/Undergrad/academic_integrity.html www.cs.nyu.edu/web/Academic/Graduate/academic_integrity.html Unfortunately, every semester we discover incidents in which students copy programming assignments from those of other students, making minor modifications so that the submitted programs are extremely similar but not identical. To help in identifying inappropriate similarities, we suggest that you and your TAs consider using Moss, a system that automatically determines similarities between programs in several languages, including C, C++, and Java. For more information about Moss, see: http://theory.stanford.edu/~aiken/moss/ Feel free to tell your students in advance that you will be using this software or any other system. And please emphasize, preferably in class, the importance of academic integrity. Rosemary Amico Assistant Director, Computer Science Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences

The university-wide policy is described here

Originally called a linkage editor by IBM.

A linker is an example of a utility program included with an operating system distribution. Like a compiler, the linker is not part of the operating system per se, i.e. it does not run in supervisor mode. Unlike a compiler it is OS dependent (what object/load file format is used) and is not (normally) language dependent.

Link, of course.

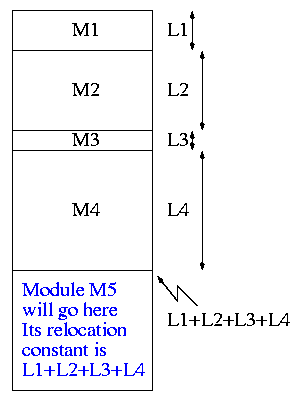

When the compiler and assembler have finished processing a module, they produce an object module that is almost runnable. There are two remaining tasks to be accomplished before object modules can be run. Both are involved with linking (that word, again) together multiple object modules. The tasks are relocating relative addresses and resolving external references.

The output of a linker is called a load module because, with relative addresses relocated and the external addresses resolved, the module is ready to be loaded and run.

The compiler and assembler (mistakenly) treat each module as if it will be loaded at location zero.

To convert this relative address to an absolute address, the linker adds the base address of the module to the relative address. The base address is the address at which this module will be loaded.

How does the linker know that Module A is to be loaded starting at location 2300?

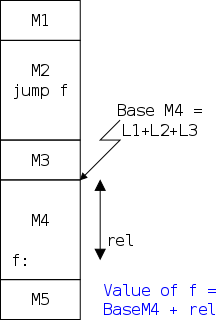

If a C (or Java, or Pascal, or Ada, etc) program contains a

function call

f(x)

to a function f() that is compiled separately, the

resulting object module must contain some kind of jump to the

beginning of

f.

To see how a linker works lets consider the following example, which is the first dataset from lab #1. The description in lab1 is more detailed.

The target machine is word addressable and each word consists of 4 decimal digits. The first (leftmost) digit is the opcode and the remaining three digits form an address.

Each object module contains three parts, a definition list, a use list, and the program text itself. Each definition is a pair (sym, loc) signifying that this symbol is defined at this location.

Each use is a symbol that will be pointed to by the program text.

The program text consists of a count N followed by N pairs (type, word), where word is a 4-digit instruction described above and type is a single character indicating if the address in the word is Immediate, Absolute, Relative, or External.

The actions taken by the linker depend on the type of the instruction, as we now illustrate. Consider the first input set from the lab.

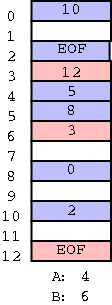

Input set #1 1 xy 2 2 z xy 5 R 1004 I 5678 E 2000 R 8002 E 7001 0 1 z 6 R 8001 E 1000 E 1000 E 3000 R 1002 A 1010 0 1 z 2 R 5001 E 4000 1 z 2 2 xy z 3 A 8000 E 1001 E 2000

The first pass simply finds the base address of each module and produces the symbol table giving the values for xy and z (2 and 15 respectively). The second pass does the real work using the symbol table and base addresses produced in pass one.

The resulting output (shown below) is more detailed than I expect you to produce. The detail is there to help me explain what the linker is doing. All I would expect from you is the symbol table and the rightmost column of the memory map.

Symbol Table xy=2 z=15 Memory Map +0 0: R 1004 1004+0 = 1004 1: I 5678 5678 2: xy: E 2000 ->z 2015 3: R 8002 8002+0 = 8002 4: E 7001 ->xy 7002 +5 0 R 8001 8001+5 = 8006 1 E 1000 ->z 1015 2 E 1000 ->z 1015 3 E 3000 ->z 3015 4 R 1002 1002+5 = 1007 5 A 1010 1010 +11 0 R 5001 5001+11= 5012 1 E 4000 ->z 4015 +13 0 A 8000 8000 1 E 1001 ->z 1015 2 z: E 2000 ->xy 2002

The honor's section must process each module separately, i.e. except for the symbol table and memory map your space requirements should be proportional to the largest module not to the sum of the modules. This does NOT make the lab harder, just better. In addition the honors class must produce a cross reference listing rather than just a symbol table as above.

Note: It is faster (less I/O)

to do a one pass approach, but is harder since you need

fix-up code

whenever a use occurs in a module that precedes

the module with the definition.

For extra credit students in either section may implement a one-pass

linker (instead of the two-pass version described above).

The linker on unix was mistakenly called ld (for loader), which is unfortunate since it links but does not load.

.TH LD 1

.SH NAME

ld \- loader

.SH SYNOPSIS

.B ld

[ option ] file ...

.SH DESCRIPTION

.I Ld

combines several

object programs into one, resolves external

references, and searches libraries.

By the mid 80s the Berkeley version (4.3BSD) man

page referred to ld as link editor

and this more accurate

name is now standard in unix/linux distributions.

During the 2004-05 fall semester a student wrote to me:

BTW - I have meant to tell you that I know the lady who wrote ld. She told me that they called it loader, because they just really didn't have a good idea of what it was going to be at the time.

Lab #1: Implement a two-pass linker. The specific assignment is detailed on the class home page.

Start Lecture #2

Homework: Read Chapter 1 (Introduction)

Software is often implemented in layers (so is hardware, but that is not the subject of this course). The higher layers use the facilities provided by lower layers.

Alternatively said, the upper layers are written using a more powerful and more abstract virtual machine than the lower layers.

In yet other words, each layer is written as though it runs on the virtual machine supplied by the lower layers and in turn provides a more abstract (pleasant) virtual machine for the higher layers to run on.

Using a broad brush, the layers are.

An important distinction is that the kernel runs in privileged/kernel/supervisor mode; whereas your programs, as well as compilers, editors, shell, linkers, browsers, etc. run in user mode. This means that the OS can access all the hardware and execute all possible instructions.

In contrast user programs cannot directly modify the hardware; for example I/O instructions are normally privileged. So the programs you and I write cannot perform I/O; but they can ask the OS to perform the I/O for them.

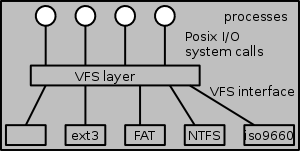

The kernel is itself normally layered, e.g.

The machine independent I/O layer is written assuming

virtual (i.e. idealized) hardware

.

For example, the machine independent I/O portion can access a

certain byte in a given file.

In reality, I/O devices, e.g., disks, have no support or knowledge

of files; these devices support only blocks.

Lower levels of the software implement files in terms of blocks.

Often the machine independent part is itself more than one layer.

The term Operating System is not well defined. Is it just the kernel, i.e., the portion run in supervisor mode? How about the libraries? The utilities? All these are certainly system software but it is not clear how much is part of the OS.

As mentioned above, the OS raises the abstraction level by providing a higher level virtual machine. A second related key objective for the OS is to manage the resources provided by this virtual machine.

The kernel itself raises the level of abstraction and hides details. For example a user (of the kernel) can write() to a file (a concept not present in hardware) and without knowing whether the file resides on a solid-state-disk (SSD), an internal scsi disk, a local USB disk, or a disk on a remote machine. The user can also ignore issues such as whether the file is stored contiguously or is broken into blocks.

Well designed abstractions are a key to managing complexity.

The kernel must manage the resources to resolve conflicts between users. Note that when we say users, we are not referring directly to humans, but instead to processes (typically) running on behalf of humans.

Often the resource is shared or multiplexed between the users. This can take the form of time-multiplexing, where the users take turns (e.g., the processor resource) or space-multiplexing, where each user gets a part of the resource (e.g., a disk drive).

With sharing comes various issues such as protection, privacy, fairness, etc.

Answer: Concurrency! Per Brinch Hansen in Operating Systems Principles (Prentice Hall, 1973) writes.

The main difficulty of multiprogramming is that concurrent activities can interact in a time-dependent manner, which makes it practically impossibly to locate programming errors by systematic testing. Perhaps, more than anything else, this explains the difficulty of making operating systems reliable.

Homework: 1. (unless otherwise stated, problems numbers are from the end of the current chapter in Tanenbaum.)

The subsection heading describe the hardware as well as the OS; we are naturally more interested in the latter. These two development paths are related as the improving hardware enabled the more advanced OS features.

One user (program; perhaps several humans) at a time. Any operating-system-like-functionality that was needed was part of the user's program.

Although this time frame predates my own usage, computers without serious operating systems existed during the second generation and were now available to a wider (but still very select) audience.

I have fond memories of the Bendix G-15 (paper tape) and the IBM 1620 (cards; typewriter; decimal). During the short time you had the machine, it was truly a personal computer.

Many jobs were batched together, but the systems were still uniprogrammed, a job once started was run to completion without interruption and then flushed from the system.

A change from the previous generation is that the OS was not reloaded for each job and hence needed to be protected from the user's execution. As mentioned above, in the first generation, the beginning of a job contained the trivial OS-like support features used.

The batches of user jobs were prepared offline (cards to magnetic tape) using a separate computer (an IBM 1401 with a 1402 card reader/punch). The tape was brought to the main computer (an IBM 7090/7094) where the output to be printed was written on another tape. This tape went back to the service machine (1401) and was printed (on a 1403).

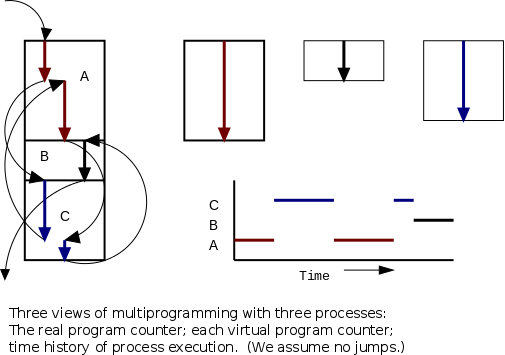

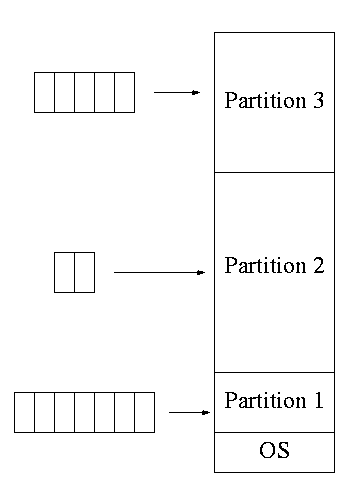

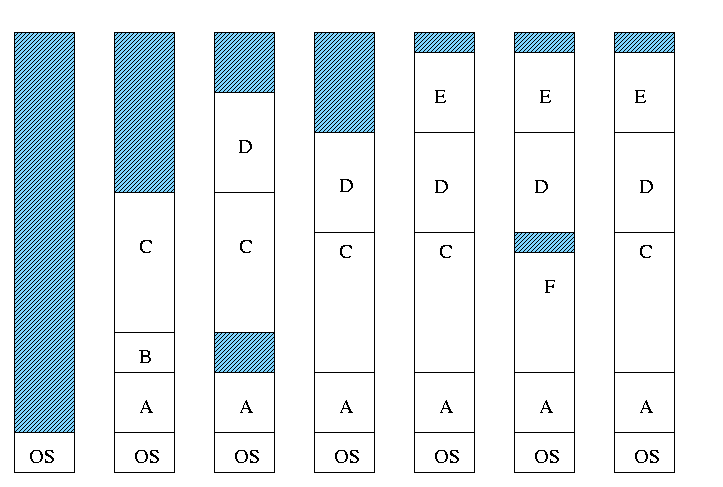

In my opinion Multiprogramming is the biggest change from the OS point of view. It is with multiprogramming (many processes executing concurrently) that we have the operating system fielding requests whose arrival order is non-deterministic. At this point operating systems become notoriously hard to get right due to the inability to test a significant percentage of the possible interactions and the inability to reproduce bugs on request.

The purpose of multiprogramming is to overlap CPU and I/O activity and thus greatly improve CPU utilization. Recall that these computers, in particular the processors, were very expensive.

efficientuser of resources, but is more difficult to implement.

holes, and fragmentation arise.

With multiprogramming, one job could be loading (from say cards),

another job could be printing, and a third computing.

So when a card deck was submitted by the user it could be read

directly into an on-disk queue.

Then when the system is ready to run another job, it is already

there.

Similarly, jobs would print

to disk and later another task

would really print these disk files onto paper.

This is multiprogramming with rapid switching between jobs

(processes) so that, to the user it appears that their job is always

running (but at a slower rate).

Also individual users spool

their own jobs on a remote

terminal.

Deciding when to switch and which process to switch to is

called scheduling.

We will study scheduling when we do processor management in a few weeks from now.

MIT and Dartmouth were pioneers in timesharing. Since I went to MIT, I naturally believe MIT was first. In particular, during my second semester (jan-may 1964), I took a course that by luck was chosen to the first one on the MIT timesharing system CTSS. I do believe that I was in the first group of undergraduates (about 15 or 20 students I guess) to use timesharing.

Serious PC Operating systems such as Unix/Linux, Windows NT/2000/XP/Vista/7/8 and (the newer versions of) MacOS are multiprogrammed.

GUIs have become important. What is not clear is whether the GUI should be part of the kernel.

Early PC operating systems were uniprogrammed and their direct descendants lasted for quite some time (e.g., Windows ME), but now all (non-embedded) OS are multiprogrammed.

Note: I very much recommend reading all of 1.2, not for this course especially, but for general interest. Tanenbaum writes well and is my age so lived through much of the history himself.

Homework:

Primarily hardware changes.

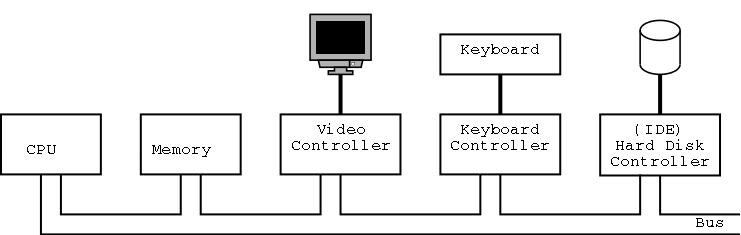

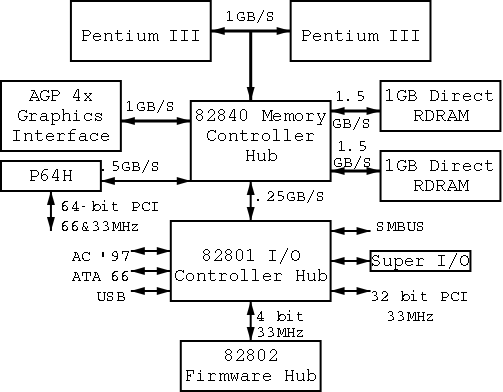

The picture above is very simplified. (For one thing, today separate buses are used to Memory and Video.)

A bus is a set of wires that connect two or more

devices.

Only one message can be on the bus at a time.

All the devices receive

the message: There are no switches in

between to steer the message to the desired destination, but often

some of the wires form an address that indicates which devices

should actually process the message.

Only at a few points will we get into sufficient detail to need to understand the various processor registers such as program counter (a.k.a, instruction pointer), stack pointers, and Program Status Words (PSWs). We will ignore computer design issues such as pipelining and superscalar.

Many of these issues are covered in 201 and nearly all of them are covered in computer architecture elective.

We do, however, need the notion of a trap, that is an instruction that atomically switches the processor into privileged mode and jumps to a pre-defined physical address. This is the key for system calls in which a user program enters the operating system. We will have much more to say about traps at the end of this chapter.

Many of the OS issues introduced by multi-processors of any flavor are also found in a uni-processor, multi-programmed system. In particular, successfully handling the concurrency offered by the second class of systems, goes a long way toward preparing for the first class. The remaining multi-processor issues are not covered in this course.

We will ignore caches (which are covered in 201 and architecture; you can see my class notes, if you are interested), but will later discuss demand paging, which is very similar. Despite their similarity, demand paging and caches use largely disjoint terminology. In both cases, the goal is to combine large, slow memory with small, fast memory to achieve the effect of large, fast memory.

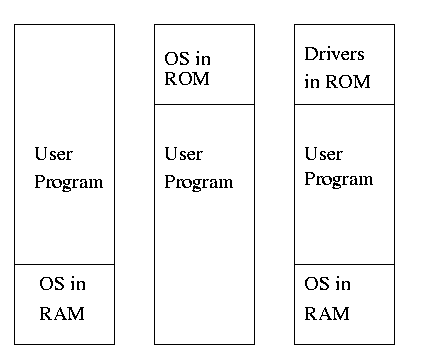

The central memory in a system is called RAM (Random Access Memory). A key point is that it is volatile, i.e. the memory loses its data if power is turned off.

ROM (Read Only Memory) is used for (low-level control) software that often comes with devices on general purpose computers, and for the entire software system on non-user-programmable devices such as microwaves and wristwatches. It is also used for non-changing data. A modern, familiar ROM is CD-ROM (or the denser DVD, or the even denser Blu-ray). ROM is non-volatile.

But often this unchangable data needs to be changed (e.g., to fix bugs). This gives rise first to PROM (Programmable ROM), which, like a CD-R, can be written once (as opposed to being mass produced already written like a CD-ROM), and then to EPROM (Erasable PROM), which is like a CD-RW. Early EPROMs needed UV light for erasure; EEPROM, Electrically EPROM or Flash RAM) can be erased by normal circuitry, which is much more convenient.

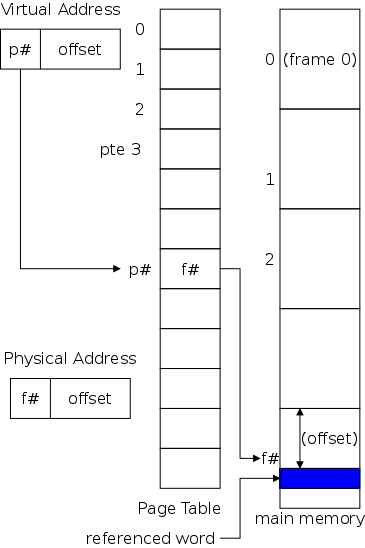

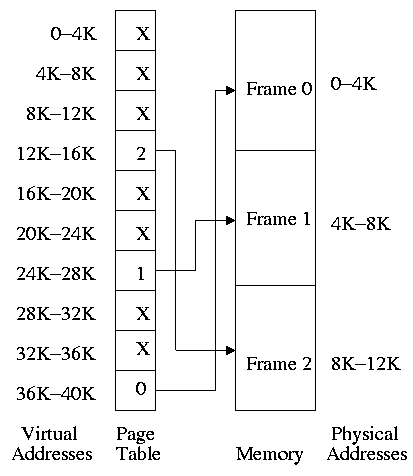

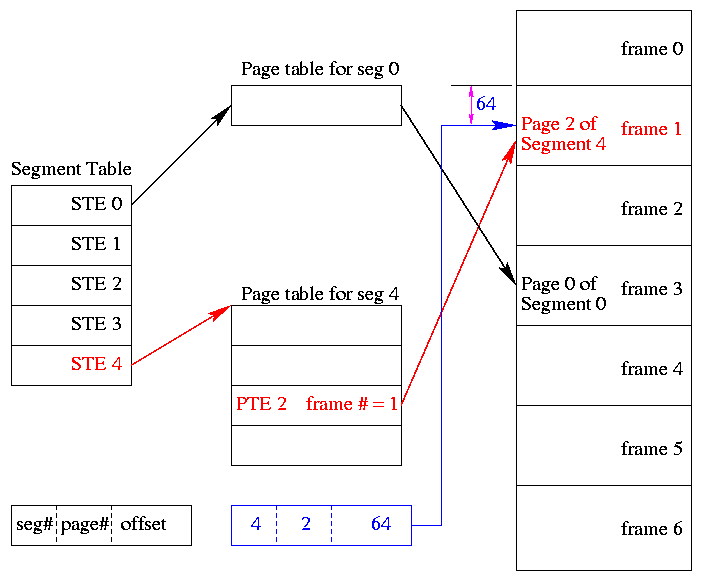

As mentioned above when discussing OS/MFT and OS/MVT, multiprogramming requires that we protect one process from another. That is we need to translate the virtual addresses (a virtual address is the address in the program itself) into physical addresses (a physical address is the actual memory address in the computer itself) such that, at any point in time, the physical address of each process are disjoint. The hardware that performs this translation is called the MMU or Memory Management Unit. (There are occasions when two processes wish to share memory.)

Note the similarity between (1) translating virtual to physical addresses by the OS and (2) relocating relative addresses (into absolute addresses) in your lab 1 linker.

When context switching from one process to another, the translation must change, which can be an expensive operation.

When we do I/O for real, I will show a real disk opened up and illustrate the components

Devices are often quite difficult to manage and a separate computer, called a controller, is used to translate OS commands into what the device requires.

This is flash RAM organized in sector-like blocks as is a disk.

Unlike RAM, SSD is non volatile; unlike a disk it has no moving

parts (and so is faster).

The blocks can be written a large number

of times.

However, the large number

is not large enough to be

completely ignored.

The bottom of the memory hierarchy, tapes have large capacities, tiny cost per byte, and very long access times. Tapes are becoming less important since their technology improvement has not kept up with the improvement in disks. We will not study tapes in this course.

In addition to the disks and tapes just mentioned, I/O devices include monitors (and graphics controllers), NICs (Network Interface Controllers), Modems, Keyboards, Mice, etc.

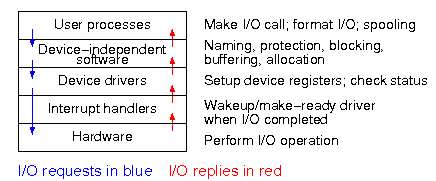

The OS communicates with the device controller, not with the device itself. For each different controller, a corresponding device driver is included in the OS. Note that, for example, many graphics controllers are capable of controlling a standard monitor, and hence the OS needs many graphics device drivers.

In theory any SCSI (Small Computer System Interconnect) controller can control any SCSI disk. In practice this is not true as SCSI gets inproved to wide scsi, ultra scsi, etc. The newer controllers can still control the older disks and often the newer disks can run in degraded mode with an older controller.

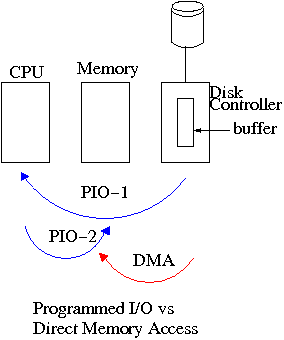

Three methods are employed.

We discuss these alternatives more in chapter 5. In particular, we explain the last point about halving bus accesses.

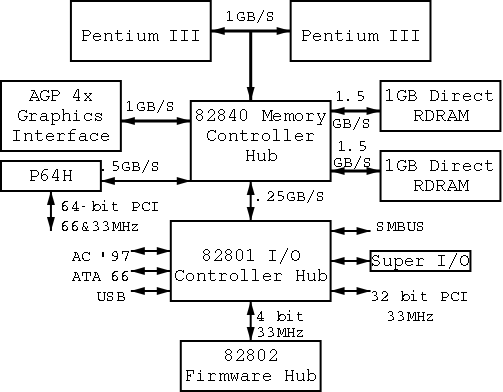

On the right is a figure showing the specifications for an Intel chip set introduced in 2000. The terminology used is not standardized, e.g., hubs are often called bridges. Most likely due to their location on the diagram to the right, the Memory Controller Hub is often called the Northbridge and the I/O Controller Hub the Southbridge.

As shown on the right this chip set has two different width PCI buses. This particular chip set supplies USB. An alternative is to have a PCI USB controller.

When the power button is pressed, control starts at the BIOS a PROM

(typically flash) in the system.

Control is then passed to (the tiny program stored in) the MBR

(Master Boot Record), which is the first 512-byte block on the

primary

disk.

Control then proceeds to the first block in the active

partition and from there the OS is finally invoked (normally via an

OS loader).

The above assumes that the boot medium selected by the bios was the hard disk. Other possibilities include a CD-ROM or the network.

There is not much difference between mainframe, server, multiprocessor, and PC OS's. Indeed the 3e considerably softened the differences given in the 2e and this continues in the 4e. For example Unix/Linux and Windows runs on all of them.

This course covers all four of those classes, which perhaps should be considered just one class .

Used in data centers, these systems ofter tremendous I/O capabilities and extensive fault tolerance.

Perhaps the most important servers today are web servers. Again I/O (and network) performance are critical.

A multiprocessor (as opposed to a multi-computer or multiple computers or computer network or grid) means multiple processors sharing memory and controlled by a single instance of the OS, which typically can run on any of the processors. Often it can run on several simultaneously.

These existed almost from the beginning of the computer age, but now are not exotic. Indeed even my laptop is a multiprocessor.

The operating system(s) controlling a system of multiple computers often are classified as either a Network OS, which is basically a collection of ordinary PCs on a LAN that use the network facilities available on PC operating systems. Some extra utilities are often present to ease running jobs on other processors.

A more sophisticated Distributed OS is a

more seamless

version of the above where the boundaries

between the processors are made nearly invisible to users (except

for performance).

This subject is not part of our course (but often is covered G22.2251).

In the recent past some OS systems (e.g., ME) were claimed to be tailored to client operation. Others felt that they were restricted to client operation. This seems to be gone now; a modern PC OS is fully functional. I guess for marketing reasons some of the functionality can be disabled.

This includes PDAs and phones, which are rapidly merging.

The only real difference between this class and the above is the

restriction to very modest memory.

However, very modest

keeps getting bigger and some phones now

include a stripped-down linux.

The OS is part of

the device, e.g., microwave ovens,

and cardiac monitors.

The OS is on a ROM so is not changed.

Since no user code is run, protection is not as important. In that respect the OS is similar to the very earliest computers. Embedded OS are very important commercially, but not covered much in this course.

Embedded systems that also contain sensors and communication devices so that the systems in an area can cooperate.

As the name suggests, time (more accurately timeliness) is an important consideration. There are two classes: Soft vs hard real time. In the latter missing a deadline is a fatal error—sometimes literally. Very important commercially, but not covered much in this course.

Very limited in power (both meanings of the word).

Start Lecture #3

This will be very brief.

Much of the rest of the course will consist of

filling in the details

.

A process is program in execution. If you run the same program twice, you have created two processes. For example if you have two editors running in two windows, each instance of the editor is a separate process.

Often one distinguishes the state or context of a process—its

address space (roughly its memory image), open files,

etc.—from the thread of control.

If one has many threads running in the same task,

the result is a multithreaded processes

.

The OS keeps information about all processes in the process table. Indeed, the OS views the process as the entry. This is an example of an active entity being viewed as a data structure (cf. discrete event simulations), an observation I first encountered in the (out of print) OS textbook by Finkel I mentioned previously.

The data contained in a process table entry enables a processes that is currently blocked or suspended to resume execution in the future.

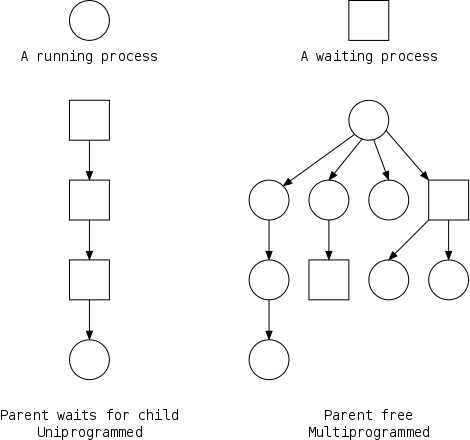

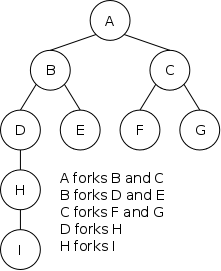

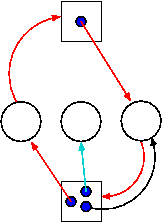

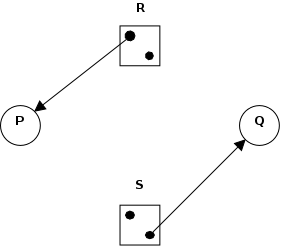

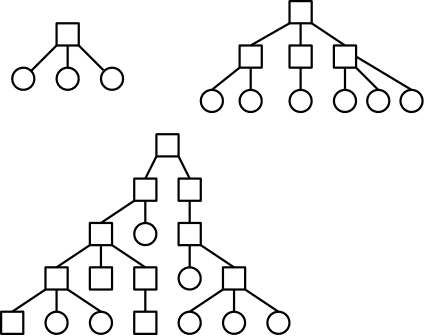

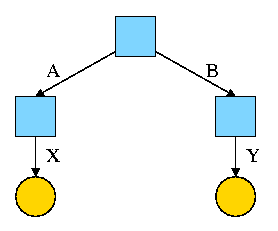

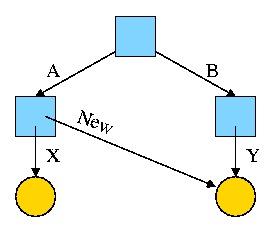

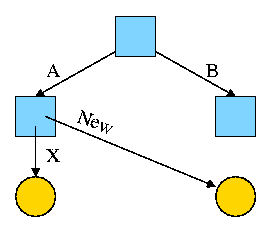

The set of processes forms a tree via the fork system call.

The forker is the parent of the forkee, which is

called a child.

If the system always blocks the parent until the child finishes, the

tree

is quite simple, just a line.

However, in modern OSes, the parent is free to continue executing and in particular is free to fork again, thereby producing another child. This produces a process tree as shown on the far right.

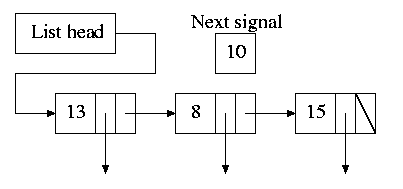

A process can send a signal to another process to

cause the latter to execute a predefined function (the signal

handler).

It can be tricky to write a program with a signal handler since the

programmer does not know when in the mainline

program the

signal handler will be invoked.

Each user is assigned a User IDentification (UID) and all processes created by that user have this UID. A child has the same UID as its parent. It is sometimes possible to change the UID of a running process. A group of users can be formed and given a Group IDentification, GID. One UID is special (the superuser or administrator) and has extra privileges.

Access to files and devices can be limited to a given UID or GID.

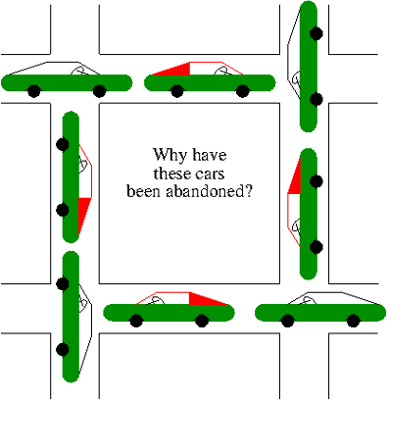

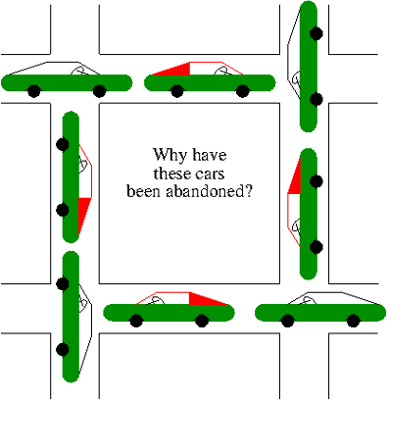

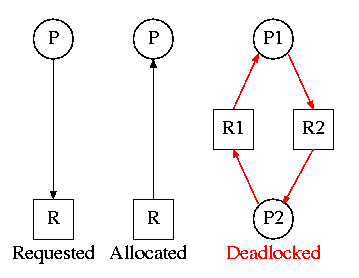

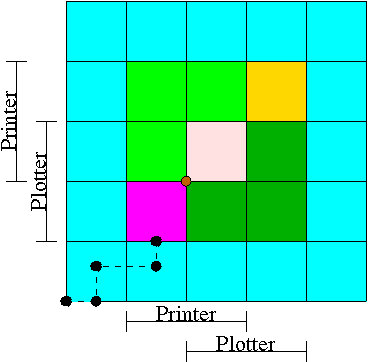

A set of processes is deadlocked if each of the processes is blocked by a process in the set. The automotive equivalent, shown below, is called gridlock. (The photograph below was sent to me by Laurent Laor, a former 2250 student.)

Clearly, each process requires memory, but there are other issues as well. For example, your linkers (will) produce a load module that assumes the process is loaded at location 0. The result is that every load module has the same (virtual) address space. The operating system must ensure that the virtual addresses of concurrently executing processes are assigned disjoint physical memory.

For another example note that current operating systems permit each process to be given more (virtual) memory than the total amount of (real) memory on the machine.

Modern systems have a hierarchy of files. A file system tree.

looks likethe parent of a:\ and c:\, but that is a feature of the UI not the file systems.

You can name a file via an absolute path starting

at the root directory (or in Windows a root directory) or via

a relative path starting at the

current working directory.

One consequence is that the OS must know the current working

directory for each process.

In addition to regular files and directories, Unix also uses the

file system namespace for devices (called

special files), which are typically found in

the /dev directory.

That is, in some ways you can treat the device as a file.

In particular some utilities that are normally applied to (ordinary)

files can be applied as well to some special files.

For example, when you are accessing a unix system using a mouse,

type the following command

cat /dev/mouse

and then move the mouse.

On my more modern system the command is

cat /dev/input/mice

You kill the cat (sorry) by typing cntl-C.

I tried this on my linux box (using a text console) and no damage occurred.

Your mileage may vary.

Before a file can be accessed, it is normally opened and a file descriptor obtained. Subsequent I/O system calls (e.g., read and write) use the file descriptor rather that the file name. This is an optimization that enables the OS to find the file once and save the information in a file table accessed by the file descriptor.

Many systems have standard files that are automatically made available to a process upon startup. These (initial) file descriptors are fixed.

A convenience offered by some command interpreters is a pipe or pipeline. For example the following command, which pipes the output of dir into a character/word/line counter, will give the number of files in the directory (plus other info).

dir | wc

There are a wide variety of I/O devices that the OS must manage. Some of these require special treatment; for example, if two processes are printing at the same time, the OS must not interleave the output.

The OS contains device specific code (drivers) for each device (really each controller) as well as device-independent I/O code.

Files and directories have associated permissions.

attributesas well. For example the linux ext2 and ext3 file systems support a

dattribute that is a hint to the dump program not to backup this file.

Memory assigned to a process, i.e., an address space, must also be protected so that unrelated processes do not read and write each others' memory.

Security has of course sadly become a very serious concern. The topic is quite deep and I do not feel that the necessarily superficial coverage that time would permit is useful so we are not covering the topic at all.

The shell presents the command line interface to the operating system and offers several convenient features.

dir | wc).

Instead of a shell, one can have a more graphical interface.

Some concepts become obsolete and then reemerge due in both cases to technology changes. Several examples follow. Perhaps the cycle will repeat with smart card OS.

The use of assembly languages greatly decreases when memories get larger. When minicomputers and microcomputers (early PCs) were first introduced, they each had small memories and for a while assembly language again became popular.

Multiprogramming requires protection hardware. Once the hardware becomes available monoprogramming becomes obsolete. Again when minicomputers and microcomputers were introduced, they had no such hardware so monoprogramming revived.

When disks are small, they hold few files and a flat (single directory) file system is adequate. Once disks get large a hierarchical file system is necessary. When mini and microcomputer were introduced, they had tiny disks and the corresponding file systems were flat.

Virtual memory, among other advantages, permits dynamically linked libraries so as VM hardware appears so does dynamic linking.

Homework: 12.

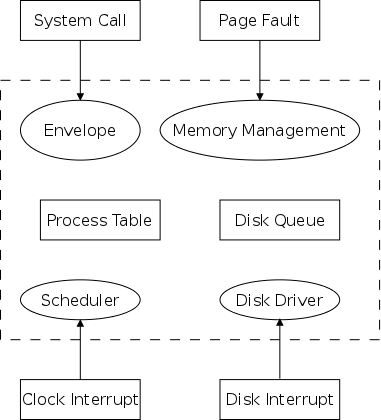

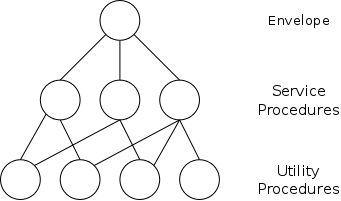

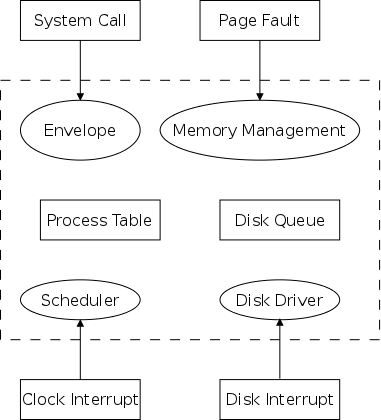

A System call is the mechanism by which a user (i.e., a process running in user mode) directly interfaces with the OS. Some textbooks use the term envelope for the component of the OS responsible for fielding system calls and dispatching them to the appropriate component of the OS. On the right is a picture showing some of the OS components and the external events for which they are the interface.

Note that the OS serves two masters. The hardware (at the bottom) asynchronously sends interrupts and the user (at the top) synchronously invokes system calls and generates page faults.

There is an important difference between these two cases.

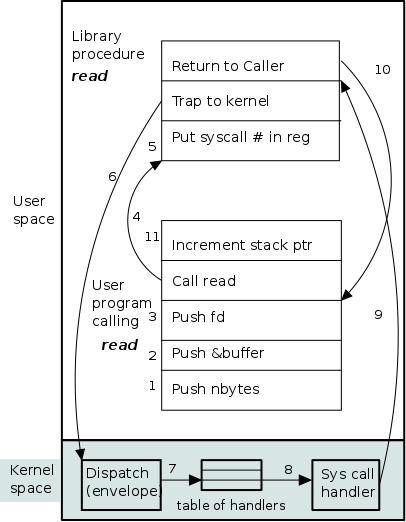

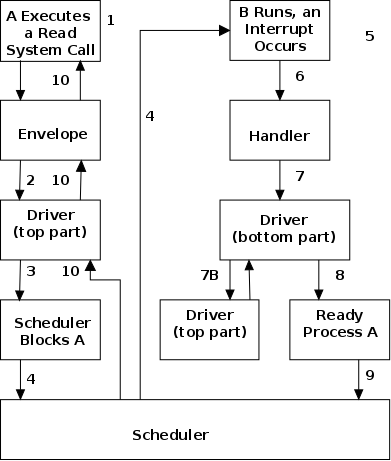

What happens when a user executes a system call such as read()? We show a detailed picture below, but at a high level, the following actions occur.

Start Lecture #4

A typical invocation of the (Unix) read system call is:

count = read(fd,buffer,nbytes)

This invocation reads up to nbytes from the file specified by the file descriptor fd into the character array buffer. The actual number of bytes read is returned (it might be less than nbytes if, for example, an end-of-file was encountered). In more detail, the steps performed are as follows.

A major complication is that the system call handler may block. Indeed, the read system call handler is likely to block. In that case a the operating system will probably switch to another process. Such process switching is far from trivial and is discussed later in the course.

| Posix | Win32 | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Process Management | ||

| Fork | CreateProcess | Clone current process |

| exec(ve) | Replace current process | |

| wait(pid) | WaitForSingleObject | Wait for a child to terminate. |

| exit | ExitProcess | Terminate process & return status |

| File Management | ||

| open | CreateFile | Open a file & return descriptor |

| close | CloseHandle | Close an open file |

| read | ReadFile | Read from file to buffer |

| write | WriteFile | Write from buffer to file |

| lseek | SetFilePointer | Move file pointer |

| stat | GetFileAttributesEx | Get status info |

| Directory and File System Management | ||

| mkdir | CreateDirectory | Create new directory |

| rmdir | RemoveDirectory | Remove empty directory |

| link | (none) | Create a directory entry |

| unlink | DeleteFile | Remove a directory entry |

| mount | (none) | Mount a file system |

| umount | (none) | Unmount a file system |

| Miscellaneous | ||

| chdir | SetCurrentDirectory | Change the current working directory |

| chmod | (none) | Change permissions on a file |

| kill | (none) | Send a signal to a process |

| time | GetLocalTime | Elapsed time since 1 jan 1970 |

We describe very briefly some of the unix (Posix) system calls. A short description of the Windows interface is in the book.

To show how the four process management calls enable much of process management, consider the following highly simplified shell.

while (true)

display_prompt()

read_command(command)

if (fork() != 0)

waitpid(...)

else

execve(command)

endif

endwhile

The fork() system call duplicates the process. That is we now have a second process, which is a child of the process that actually executed the fork(). The parent and child are very, very nearly identical. For example they have the same instructions, they have the same data, and they are both currently executing the fork() system call.

But there is a difference!

The fork() system call returns a zero in the child process and returns a positive integer in the parent. In fact the value returned to the parent is the PID (process ID) of the child.

Thus, the parent and child execute different branches of the if-then-else in the code above.

Note that simply removing the waitpid(...) gives background jobs.

Most files are accessed sequentially from beginning to end.

In this case the operations performed are

open() -- possibly creating the file

multiple read()s and write()s

close()

For non-sequential access, lseek is used to move

the File Pointer

, which is the location in the file where the

next read or write will take place.

Directories are created and destroyed by mkdir and rmdir. Directories are changed by the creation, modification, and deletion of files. As mentioned, open can create files. Files can have several names link gives another name to an existing file and unlink removes a name. When the last name is gone (and the file is no longer open by any process), the file data is destroyed. This description is approximate, we give the details later in the course.

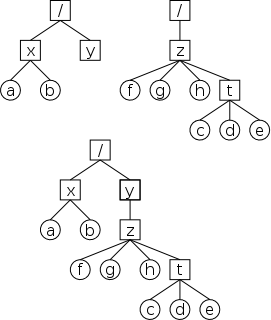

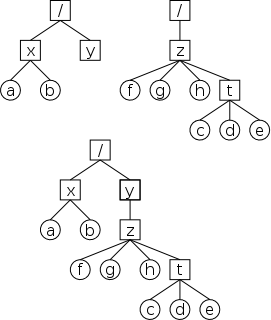

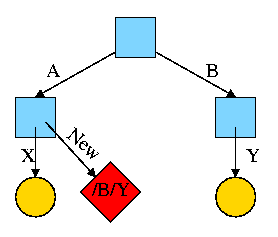

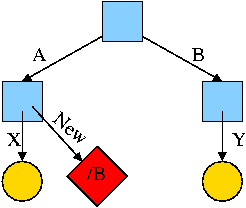

In Unix, one file system can be mounted on (attached to) another. When this is done, access to an existing directory on the second filesystem is temporarily replaced by the entire first file system. Most often the directory chosen is empty before the mount so no files become (temporarily) invisible.

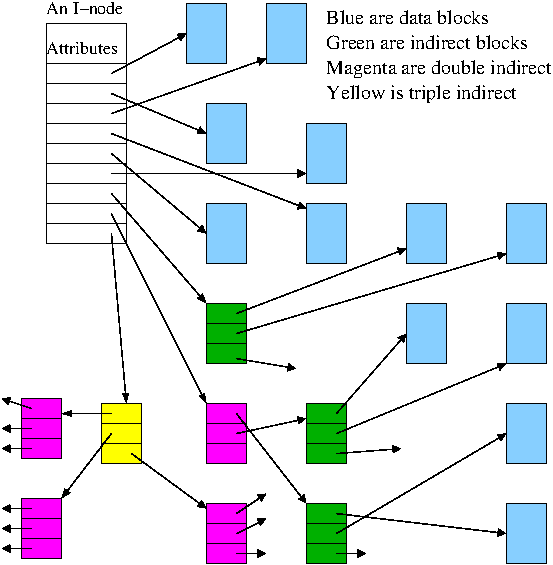

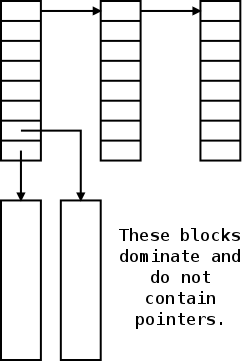

The top picture shows two file systems; the second row shows the result when the right hand file system is mounted on /y. In both cases squares represent directories and circles represent regular files.

This is how, on a Unix system all files, even those on different physical disks and using different filesystems, can still all be descendants of a single root

Skipped

Skipped

Homework: For each of the following system calls, give a condition that causes it to fail: fork, exec, and unlink.

The transfer of control between user processes and the operating system kernel can be quite complicated, especially in the case of blocking system calls, hardware interrupts, and page faults. Before tackling these issues later, we begin with the familiar example of a procedure call within a user-mode process.

An important OS objective is that, even in the more complicated cases of page faults and blocking system calls requiring device interrupts, simple procedure call semantics are observed from a user process viewpoint. The complexity is hidden inside the kernel itself, yet another example of the operating system providing a more abstract, i.e., simpler, virtual machine to the user processes.

More details will be added when we study memory management (and know officially about page faults) and more again when we study I/O (and know officially about device interrupts).

A number of the points below are far from standardized.

Such items as where to place parameters, which routine saves the

registers, exact semantics of trap, etc, vary as one changes

language/compiler/OS.

Indeed some of these are referred to as calling conventions

,

i.e. their implementation is a matter of convention rather than

logical requirement.

The presentation below is, we hope, reasonable, but must be viewed

as a generic description of what could happen, rather than a real

description of what does happen with, say, C compiled by the

Microsoft compiler running on Windows 7.

Procedure f calls g(a,b,c) in process P. An example is above where a user program calls read(fd,buffer,nbytes). Note that both f() and g() are in the same process P and no action goes outside P. Thus we will not mention the process again in this description.

stack-like) structure of control transfer: we can be sure that control will return to f() when the call to g() exits. The above statement holds even if g() calls h() and then h() calls d(). In fact it even holds if, via recursion, g() calls f(). (We are ignoring language features such as

throwingand

catchingexceptions, and the use of unstructured assembly coding. In the latter cases all bets are off.)

We mean one procedure running in kernel mode calling another procedure, which will also be run in kernel mode Later, we will discuss switching from user mode to kernel mode and back.

There is not much difference between the actions taken during a kernel-mode procedure call and during a user-mode procedure call. The procedures executing in kernel-mode are permitted to issue privileged instructions, but the instructions used for transferring control are all unprivileged so there is no change in that respect.

One difference is that often a different stack is used in kernel mode, but that simply means that the stack pointer must be set to the kernel stack when switching from user to kernel mode. But we are not switching modes in this section; the stack pointer already points to the kernel stack. Often there are two stack pointers one for kernel mode and one for user mode.

The trap instruction, like a procedure call, is a synchronous transfer of control: We can see where, and hence when, it is executed. In this respect, there are no surprises. Although not surprising, the trap instruction does have an unusual effect: processor execution is switched from user-mode to kernel-mode. That is, the trap instruction normally itself is executed in user-mode (it is naturally an UNprivileged instruction), but the next instruction executed (which is NOT the instruction written after the trap) is executed in kernel-mode.

Process P, running in unprivileged (user) mode, executes a trap.

The code being executed is written in assembler since there are no

high level languages that generate a trap instruction.

There is no need to name the function that is executing.

Compare the following example to the explanation of f calls g

given above.

nameof the code-sequence to which the processor will jump rather than as an argument to trap.

interruptappears because an RTI is also used when the kernel is returning from an interrupt as well as the present case when it is returning from an trap.

Remark: A good way to use the material in the addendum is to compare the first case (user-mode f calls user-mode g) to the TRAP/RTI case line by line so that you can see the similarities and differences.

I must note that Tanenbaum is a big advocate of the so called microkernel approach in which as much as possible is moved out of the (supervisor mode) kernel into separate processes. The (hopefully small) portion left in supervisor mode is called a microkernel.

In the early 90s this was popular.

Digital Unix (subsequently called True64) and Windows

NT/2000/XP/Vista/7/8 are examples.

Digital Unix was based on Mach, a research OS from Carnegie Mellon

university.

Lately, the growing popularity of Linux has called into question the

belief that

all new operating systems will be microkernel based

.

The previous picture: one big program.

The system switches from user mode to kernel mode during the poof and

then back when the OS does a return

(an RTI or return

from interrupt).

While in supervisor mode, the OS naturally includes procedure calls and returns.

Modern monolithic systems, such as Windows and Linux, are not completely monolithic in that during execution, they can load code modules as needed. This load on demand capability is mainly used for device drivers.

We can structure the system better the above might suggest, which brings us to ...

Some systems have more layers and are more strictly structured.

An early layered system was THE

operating system by

Dijkstra and his students at Technische Hogeschool Eindhoven.

This was a simple batch system so the operator

was the user.

The actual layers were

The layering was done by convention, i.e. there was no enforcement by hardware and the entire OS is linked together as one program. This is true of many modern OS systems as well (e.g., linux).

The MULTICS system was layered in a more formal manner. The hardware provided several protection layers and the OS used them. That is, arbitrary code could not jump into or access data in a more protected layer.

The idea is to have the kernel, i.e. the portion running in supervisor mode, as small as possible and to have most of the operating system functionality provided by separate processes. The microkernel provides just enough to implement processes.

This does have advantages. For example an error in the file server cannot corrupt memory in the process server since they have separate address spaces (they are after all separate process). Confining the effect of errors makes them easier to track down. Also an error in the ethernet driver can corrupt or stop network communication, but it cannot crash the system as a whole.

But the microkernel approach does mean that when a (real) user process makes a system call there are more processes switches. These are not free.

Related to microkernels is the idea of putting the mechanism in the kernel, but not the policy. For example, the kernel would know how to select the highest priority process and run it, but some user-mode process would assign the priorities. One could envision changing the priority scheme being a relatively minor event compared to the situation in monolithic systems where the entire kernel must be relinked and rebooted.

Dennis Ritchie, the inventor of the C programming language and co-inventor, with Ken Thompson, of Unix was interviewed in February 2003. The following is from that interview.

What's your opinion on microkernels vs. monolithic?

They're not all that different when you actually use them.Microkernels tend to be pretty large these days,monolithickernels with loadable device drivers are taking up more of the advantages claimed for microkernels.

I should note, however, that Tanenbaum's Minix microkernel (excluding the processes) is quite small, about 13,000 lines.

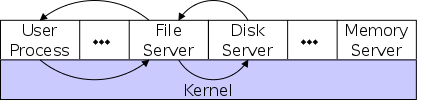

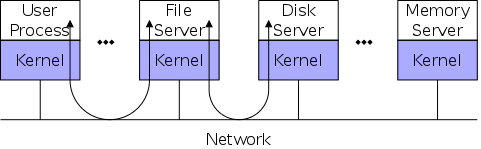

When implemented on one computer, a client-server OS often uses the microkernel approach in which the microkernel just handles communication between clients and servers, and the main OS functions are provided by a number of separate processes.

A distributed system can be thought of as an extension of the client server concept where the servers are remote.

The figure on the right would describe a distributed system of yesteryear, where memory was scarce and it would be considered lavish to have full systems on each machine.

Today with plentiful memory, each machine would have all the different servers. So the only reason am OS-internal message would go to another computer is if the originating process wished to communicate with a specific process on that computer (for example wanted to access a remote disk).

Distributed systems are becoming increasingly important for application programs. Perhaps the program needs data found only on certain machine (no one machine has all the data). For example, think of (legal, of course) file sharing programs.

Homework: The client-server model is popular in distributed systems. Can it also be used in single-computer system?

Use a hypervisor

(i.e., beyond supervisor, i.e. beyond a

normal OS) to switch between multiple

Operating Systems.

A more modern name for a hypervisor is a

Virtual Machine Monitor (VMM)

.

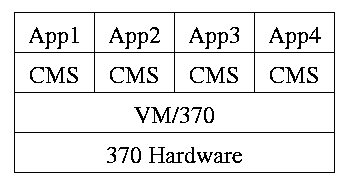

The hypervisor idea was made popular by IBM's CP/CMS (now VM/370). CMS stood for Cambridge Monitor System since it was developed at IBM's Cambridge (MA) Science Center. It was renamed, with the same acronym (an IBM specialty, cf. RAID) to Conversational Monitor System.

Recently, virtual machine technology has moved to machines (notably

x86) that are not fully virtualizable.

Recall that when CMS executed a privileged instruction, the hardware

trapped to the real operating system.

On x86, privileged instructions are ignored when executed

in user mode, so running the guest OS in user mode won't work.

Bye bye (traditional) hypervisor.

But a new style emerged where the hypervisor runs, not on the

hardware, but on the host operating system.

See the text for a sketch of how this (and another idea

paravirtualization

) works.

An important research advance was Disco from Stanford University

that led to the successful commercial product VMware.

Both AMD and Intel have extended the x86 architecture to better support virtualization. The newest processors produced today (2008) by both companies now support an additional (higher) privilege mode for the VMM. The guest OS now runs in the old privileged mode (for which it was designed) and the hypervisor/VMM runs in the new higher privileged mode from which it is able to monitor the usage of hardware resources by the guest operating system(s).

The idea is that a new (rather simple) computer architecture called the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) was invented but not built (in hardware). Instead, interpreters for this architecture are implemented in software on many different hardware platforms. Each interpreter is also called a JVM. The java compiler transforms java into instructions for this new architecture, which then can be interpreted on any machine for which a JVM exists.

This has portability as well as security advantages, but at a cost in performance.

Of course java can also be compiled to native code for a particular hardware architecture and other languages can be compiled into instructions for a software-implemented virtual machine (e.g., pascal with its p-code).

Similar to VM/CMS but the virtual machines have disjoint resources (e.g., distinct disk blocks) so less remapping is needed.

Assumed knowledge.

Assumed knowledge.

Mostly assumed knowledge. Linker's are very briefly discussed. Our earlier discussion was much more detailed.

Extremely brief treatment with only a few points made about the running of the operating itself.

Skipped

Skipped

Assumed knowledge. Note that what is covered is just the prefixes, i.e. the names and abbreviations for various powers of 10.

Skipped, but you should read and be sure you understand it (about 2/3 of a page).

Tanenbaum's chapter title is Processes and Threads

.

I prefer to add the word management.

The subject matter is processes, threads, scheduling, interrupt

handling, and IPC (Inter-Process Communication—and

Coordination).

Definition: A process is a program in execution.

Even though in actuality there are many processes running at once, the OS gives each process the illusion that it is running alone.

Virtual time is the time used by just this processes.

Virtual time progresses at a rate independent of other processes.

(Actually, this is false, the virtual time is typically

incremented a little during the systems calls used for process

switching; so if there are other processes, overhead

virtual time occurs.)

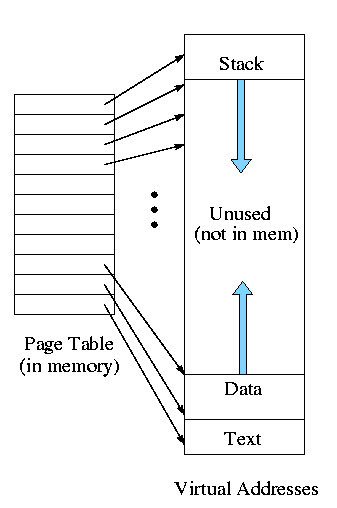

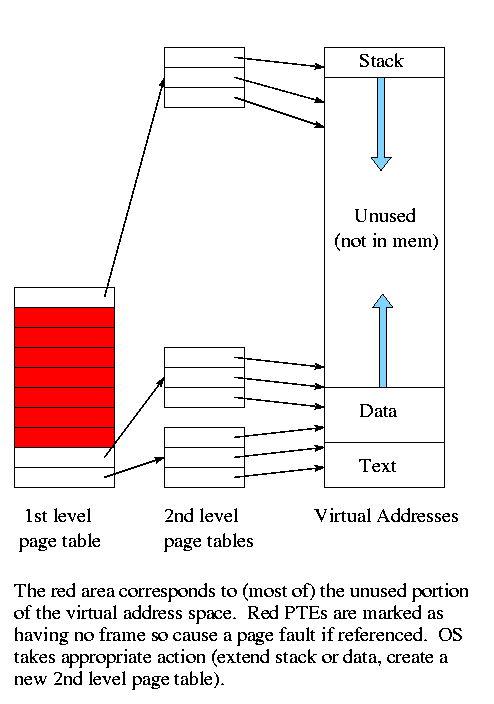

Virtual memory is the memory as viewed by the process.

Each process typically believes it has a contiguous chunk of memory

starting at location zero.

Of course this can't be true of all processes (or they would be

using the same memory) and in modern systems it is actually true of

no processes (the memory assigned to a single process is not

contiguous and does not include location zero).

Think of the individual modules that are input to the linker.

Each numbers its addresses from zero; the linker eventually

translates these relative addresses into absolute addresses.

That is the linker provides to the assembler a virtual memory in

which addresses start at zero.

Virtual time and virtual memory are examples of abstractions provided by the operating system to the user processes so that the latter experiences a more pleasant virtual machine than actually exists.

Start Lecture #5

From the users' or external viewpoint there are several mechanisms for creating a process.

But looked at internally, from the system's viewpoint, the second

method dominates.

Indeed, in early versions of Unix only one process

(called init) is created at system initialization; all the

others are created by the fork() system call.

Question: Why have init?

That is why not have all processes created via method 2?

Answer: Because without init there would be no

running process to create any others.

Many systems have daemon

process lurking around to perform

tasks when they are needed.

I was pretty sure the terminology was related to mythology, but

didn't have a reference until a student found

The {Searchable} Jargon Lexicon

at http://developer.syndetic.org/query_jargon.pl?term=demon

daemon: /day'mn/ or /dee'mn/ n. [from the mythological meaning, later rationalized as the acronym `Disk And Execution MONitor'] A program that is not invoked explicitly, but lies dormant waiting for some condition(s) to occur. The idea is that the perpetrator of the condition need not be aware that a daemon is lurking (though often a program will commit an action only because it knows that it will implicitly invoke a daemon). For example, under ITS (a very early OS), writing a file on the LPT spooler's directory would invoke the spooling daemon, which would then print the file. The advantage is that programs wanting (in this example) files printed need neither compete for access to nor understand any idiosyncrasies of the LPT. They simply enter their implicit requests and let the daemon decide what to do with them. Daemons are usually spawned automatically by the system, and may either live forever or be regenerated at intervals. Daemon and demon are often used interchangeably, but seem to have distinct connotations. The term `daemon' was introduced to computing by CTSS people (who pronounced it /dee'mon/) and used it to refer to what ITS called a dragon; the prototype was a program called DAEMON that automatically made tape backups of the file system. Although the meaning and the pronunciation have drifted, we think this glossary reflects current (2000) usage.

As is often the case, wikipedia.org proved useful. Here is the first paragraph of a more thorough entry. The wikipedia also has entries for other uses of daemon.

In Unix and other computer multitasking operating systems, a daemon is a computer program that runs in the background, rather than under the direct control of a user; they are usually instantiated as processes. Typically daemons have names that end with the letter "d"; for example, syslogd is the daemon which handles the system log.

Again from the outside there appear to be several termination mechanism.

And again, internally the situation is simpler.

In Unix

terminology, there are two system calls kill and

exit that are used.

kill (poorly named in my view) sends a signal to another

process.

For many signals, if the signal is not caught (via

the signal system call) the process is terminated.

There is also an uncatchable

signal.

The exit system call is used for self termination and can

indicate success or failure.

Modern general purpose operating systems permit a user to create and destroy processes.

Old or primitive operating system like MS-DOS are not fully multiprogrammed, so when one process starts another, the first process is automatically blocked and waits until the second is finished. This implies that the process tree degenerates into a line.

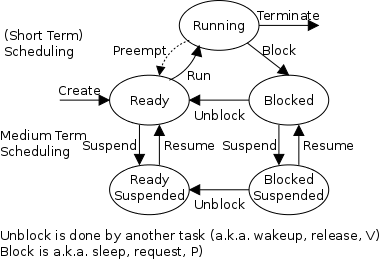

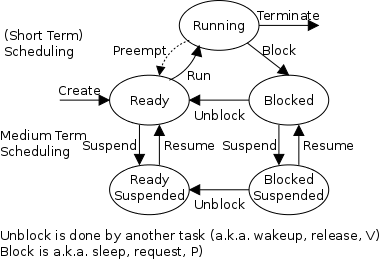

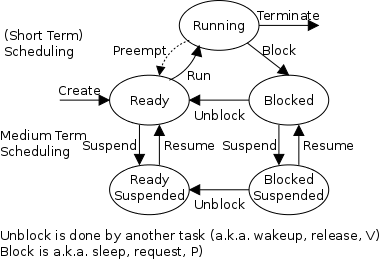

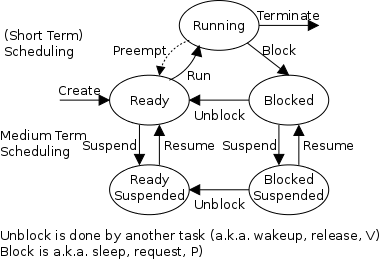

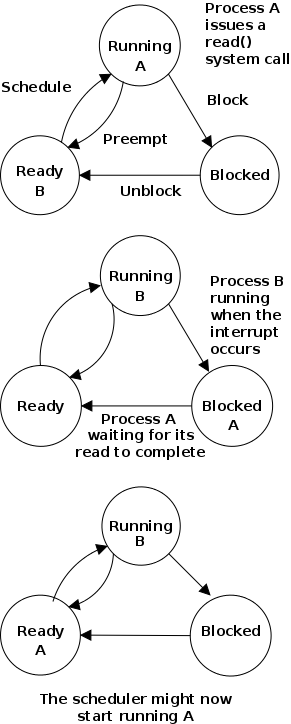

The diagram on the right contains much information. I often include it on exams.

Consider a running process P that issues an I/O request.

A preemptive scheduler has the dotted line preempt;

A non-preemptive scheduler doesn't.

The number of processes changes only for two arcs: create and terminate.

Suspend and resume are medium term scheduling.

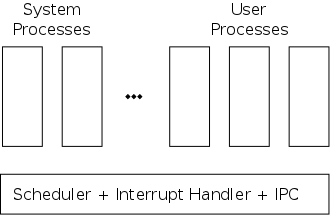

One can organize an OS around the scheduler.

kernel(a micro-kernel) consisting of the scheduler, interrupt handlers, and IPC (interprocess communication).

Minixoperating system works this way.

The OS organizes the data about each process in a table naturally called the process table. Each entry in this table is called a process table entry or process control block (PCB).

Characteristics of the process table.

an active entity becomes a data structure when looked at from a lower level.

This should be compared with the addenda on transfer of control and trap.

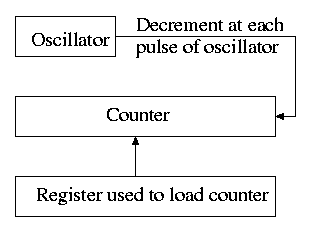

In a well defined location in memory (specified by the hardware) the OS stores an interrupt vector, which contains the address of the interrupt handler.

Assume a process P is running and a disk interrupt occurs for the completion of a disk read previously issued by process Q, which is currently blocked. Note that disk interrupts are unlikely to be for the currently running process (because the process that initiated the disk access is likely blocked).

this instruction caused the interrupt.

this instruction immediately preceeded the interrup.

program, namely the OS, and hence might well be using the same variables. We will soon see how this can cause great problems even in what appear to be trivial cases.

Asa User Process

In traditional Unix and Linux, if an interrupt occurs while a user process with PID=P is running, the system switches to kernel mode and OS code is executed, but the PID is still P. The owner of process P is charged for this execution. Try running the time program on one of the Unix systems and noting the output.

Consider a job that is unable to compute (i.e., it is waiting for I/O) a fraction p of the time.

There are at least two causes of inaccuracy in the above modeling procedure.

Nonetheless, it is correct that increasing MPL does increase CPU utilization up to a point.

An important limitation is memory. That is, we assumed that we have many jobs loaded at once, which means we must have enough memory for them. There are other memory-related issues as well and we will discuss them later in the course.

Homework:

Start Lecture #6

Remark: ITS says everyone added to the class should have an account on i5.nyu.edu. Let me know if you do not.

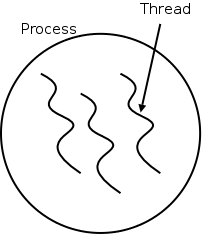

The idea behind threads to have separate threads of control (hence the name) running in the address space of a single process as shown in the diagram to the right. An address space is a memory management concept. For now think of an address space as the memory in which a process runs. (In reality it also includes the mapping from virtual addresses, i.e., addresses in the program, to physical addresses, i.e., addresses in the machine.

Each thread is somewhat like a process (e.g., it shares the processor with other threads) but a thread contains less state than a process (e.g., the address space belongs to the process in which the thread runs.)

Often, when a process P executing an application is blocked (say for I/O), there is still computation that can be done for the application. Another process can't do this computation since it doesn't have access to P's memory. But two threads in the same process do share memory so that problem doesn't occur.

The downside of this memory sharing among threads is that each

thread is not protected from the others in its process.

We will see in section 2.3 that having multiple threads concurrently

accessing the same memory can cause subtle bugs is programs that

look too simple

to be wrong.

So it is a performance/simplicity trade-off.

loop Read 10KB from disk1 to inBuffer Compute from inBuffer to outBuffer Write outBuffer to disk2 end loop // process 1 loop Read data from disk1 to inBuffer end loop // process 2 loop Compute from inBuffer to outBuffer end loop // process 3 loop Write outBuffer to disk2 end loop

Consider the first frame of code on the right. Assume for simplicity each line takes 10ms so the entire loop processes 10KB every 30ms. However, the CPU is busy only during the second line and, (if the I/O system is sophisticated), the first and third lines use separate hardware.

Hence in principle the three lines could all proceed at the same time. That is we could turn the three steps into a pipeline so that after the startup phase, the loop would process 10KB every 10ms, a 3X speed improvement.

The second frame show an attempt to speed up the application by splitting it into three processes: a reader, a computer, and a writer. However this can't work since the two inBuffers are not the same so processes 1 and 2 aren't communicating. Similarly for processes 2 and 3.

If instead the three loops were each a thread within the same process, then the two uses of inBuffer would refer to the same variable and similarly for outBuffer and hence our desired speedup would occur.

Another advantage of the threaded solution over the separate process non-solution, is that the system can switch between threads in the same process faster than it can switch between separate processes.

(Actually it is not this easy. Users of the same buffer must coordinate their actions, and you need at least two inBuffers and two outBuffers.)

An important modern example of threading is a multithreaded web

server.

Each thread is responding to a single WWW connection.

While one thread is blocked on I/O, another thread can be processing

another WWW connection.

Question: Why not use separate processes, i.e.,

what is the shared memory?

Answer: The cache of frequently referenced

pages.

A common organization for a multithreaded application is to have a dispatcher thread that fields requests and then passes each request on to an idle worker thread. Since the dispatcher and worker share memory, passing the request is very low overhead.

A final (related) example occurs when a main line task interfaces with the user and sometimes needs to perform a lengthy task that does not directly affect the user-interface.

Tanenbaum considers a word processor currently editing a large file (say a book the user is writing) and the user deletes a word early in the book. This can cause changes on all subsequent pages, which could cause a detectable delay in the user interface. With threads, a second thread can be assigned the reformatting task while the primary thread continues to interface with the user. It is only when the user wishes to examine a page near the end of the book that they must wait for the second thread to finish. Hopefully, the user has been doing other editing in the beginning of the book so that the second thread is finished prior to the user needing to access pages near the end. Even if the second thread is not finished, it will have accomplished some of the work while the user is still editing near the book's beginning.

In this same example, the word processor may wish to perform automatic backups. Again another thread to do this. In this way the thread that interfaces with the user is not blocked during the backup. However some coordination between threads may be needed so that the backup is of a consistent state.

| Per process items | Per thread items |

|---|---|

| Address space | Program counter |

| Global variables | Machine registers |

| Open files | Stack |

| Child processes | |

| Pending alarms | |

| Signals and signal handlers | |

| Accounting information |

A process contains a number of resources such as address space, open files, accounting information, etc. In addition to these resources, a process has a thread of control, e.g., program counter, register contents, stack. The idea of threads is to permit multiple threads of control to execute within one process. This is often called multithreading and threads are sometimes called lightweight processes. Because threads in the same process share so much state, switching between them is much less expensive than switching between separate processes. The table on the right shows which properties are common to all threads in a given process and which properties are thread specific.

Individual threads within the same process are not completely independent. For example there is no memory protection between them. This is typically not a security problem as the threads are cooperating and all are from the same user (indeed the same process). However, the shared resources do make debugging harder. For example one thread can easily overwrite data needed by another thread in the process and when the second thread fails, the cause may be hard to determine because the tendency is to assume that the failed thread caused the failure.

You may recall that a serious advantage

of microkernel

OS design was that the separate OS processes

could not, even if buggy, damage each others data structures.

A new thread in the same process is created by a routine named something like thread_create; similarly there is thread_exit. The analogue to waitpid is thread_join (the name comes presumably from the fork-join model of parallel execution).

The routine tread_yield, which relinquishes the processor, does not have a direct analogue for processes. The corresponding system call (if it existed) would move the process from running to ready. It would be as if the process preempted itself.

Homework: 15.

Assume a process has several threads. What should we do if one of these threads

POSIX threads (pthreads) is an IEEE standard specification that is supported by many Unix and Unix-like systems. Pthreads follows the classical thread model above and specifies routines such as pthread_create, pthread_yield, etc.

An alternative to the classical model are the so-called Linux threads, which are discussed in section 10.3 of the 4e).

Write a (threads) library that acts as a mini-scheduler and implements thread_create, thread_exit, thread_wait, thread_yield, etc. This library acts as a run-time system for the threads in this process. The central data structure maintained and used by this library is a thread table, the analogue of the process table in the operating system itself.

There is a thread table and an instance of the threads library in each multithreaded process.

Advantages of User-Mode Threads

:

Disadvantages

For a uniprocessor, which is all we are officially considering, there is little gain in splitting pure computation into pieces. If the CPU is to be active all the time for all the threads, it is simpler to just have one (unithreaded) process.

But this changes for multiprocessors/multicores. Now it is very useful to split computation into threads and have each executing on a separate processor/core. In this case, user-mode threads are wonderful, there are no system calls and the extremely low overhead is beneficial.

However, there are serious issues involved is programming applications for this environment.

One can move the thread operations into the operating system itself. This naturally requires that the operating system itself be (significantly) modified and is thus not a trivial undertaking.

One can write a (user-level) thread library even if the kernel also has threads. This is sometimes called the N:M model since N user-mode threads run on M kernel threads. In this scheme, the kernel threads cooperate to execute the user-level threads.

An offshoot of the N:M terminology is that kernel-level threading (without user-level threading) is sometimes referred to as the 1:1 model since one can think of each thread as being a user level thread executed by a dedicated kernel-level thread.

Homework: 16, 18.

Skipped

The idea is to automatically issue a thread-create system call upon message arrival. (The alternative is to have a thread or process blocked on a receive system call.) If implemented well, the latency between message arrival and thread execution can be very small since the new thread does not have state to restore.

Definitely NOT for the faint of heart.

Remark: We shall do section 2.4 before section 2.3 for two reasons.

Scheduling processes on the processor is often called

processor scheduling

or process scheduling

or

simply scheduling

.

As we shall see later in the course, a more descriptive name would

be short-term, processor scheduling

.

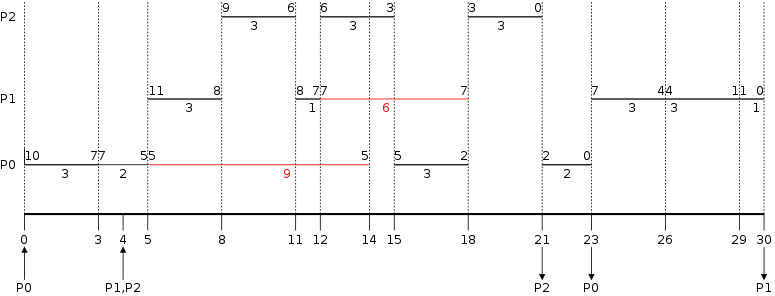

For now we are discussing the arcs connecting running↔ready in the diagram on the right showing the various states of a process. Medium term scheduling is discussed later as is disk-arm scheduling.

As you would expect, the part of the OS responsible for (short-term, processor) scheduling is called the (short-term, processor) scheduler and the algorithm used is called the (short-term, processor) scheduling algorithm.

Early computer systems were monoprogrammed and, as a result, scheduling was a non-issue.

For many current personal computers, which are definitely multiprogrammed, there is in fact very rarely more than one runnable process. As a result, scheduling is not critical.

For servers, scheduling is indeed important and these are the systems you should think of.

Processes alternate CPU bursts with I/O activity, as we shall see in lab2. The key distinguishing factor between compute-bound (aka CPU-bound) and I/O-bound jobs is the length of the CPU bursts.

The trend over the past decade or two has been for more and more jobs to become I/O-bound since the CPU speed has increased much faster than I/O speed. However, this trend is not expected to continue as aggressively.

An obvious point, which is often forgotten (I don't think 4e mentions it) is that the scheduler cannot run when the OS is not running. In particular, for the uniprocessor systems we are considering, no scheduling can occur when a user process is running. (In the mulitprocessor situation, no scheduling can occur when all processors are running user jobs).

Again we refer to the state transition diagram above.

It is important to distinguish preemptive from non-preemptive scheduling algorithms.

run until completion, or block (, or yield).

preemptarc in the diagram is present for preemptive scheduling algorithms.

We distinguish three categories of scheduling algorithms with regard to the importance of preemption.

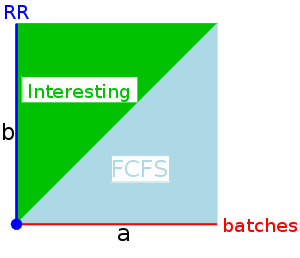

For multiprogramed batch systems (we don't consider uniprogrammed systems, which don't need schedulers) the primary concern is efficiency. Since no user is waiting at a terminal, preemption is not crucial and if it is used, each process is given a long time period before being preempted.

For interactive systems (and multiuser servers), preemption is crucial for fairness and rapid response time to short requests.

We don't study real time systems in this course, but can say that preemption is typically not important since all the processes are cooperating and are programmed to do their task in a prescribed time window.

There are numerous objectives, several of which conflict, that a scheduler tries to achieve. These include.

jobto its termination. This is important for batch jobs.

shortest job first.

wasted cyclesand limited logins for repeatability.

This is used for real time systems. The objective of the scheduler is to find a schedule for all the tasks (there are a fixed set of tasks) so that each meets its deadline. The run time of each task is known in advance.

Actually it is more complicated.

There is an amazing inconsistency in naming the different (short-term) scheduling algorithms. Over the years I have used primarily 4 books: In chronological order they are Finkel, Deitel, Silberschatz, and Tanenbaum. The table just below illustrates the name game for these four books. After the table we discuss several scheduling policy in some detail.

Finkel Deitel Silbershatz Tanenbaum ------------------------------------- FCFS FIFO FCFS FCFS RR RR RR RR PS ** PS PS SRR ** SRR not in tanenbaum SPN SJF SJF SJF/SPN PSPN SRT PSJF/SRTF SRTN HPRN HRN ** not in tanenbaum ** ** MLQ only in silbershatz FB MLFQ MLFQ MQ

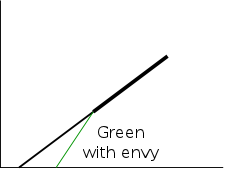

Remark: For an alternate organization of the scheduling algorithms (due to my former PhD student Eric Freudenthal and presented by him Fall 2002) click here.

If the OS doesn't

schedule, it still needs to store the list

of ready processes in some manner.

If it is a queue you get FCFS.

If it is a stack (strange), you get LCFS.

Perhaps you could get some sort of random policy as well.

Sort jobs by execution time needed and run the shortest first.

This is a Non-preemptive algorithm.

First consider a static (overly simple, non-realistic) situation

where all jobs are available in the beginning and we know how long

each one takes to run.

For simplicity lets consider run-to-completion

, also

called uniprogrammed

(i.e., we don't even switch to another

process on I/O).

In this situation, uniprogrammed SJF has the shortest average waiting time. Here's why.

Start Lecture #7

The above argument illustrates an advantage of favoring short jobs (e.g., RR with small quantum): The average waiting time is reduced.

In the more realistic case of true SJF where the scheduler switches to a new process when the currently running process blocks (say for I/O), we would call the policy shortest next-CPU-burst first. However, I have never heard anyone (except me) call it that.

The real difficulty is predicting the future (i.e., knowing in advance the time required for the job or the job's next-CPU-burst).

One way to estimate the duration of the next CPU burst is to calculate a weighted average of the duration of recent bursts. Tanenbaum calls this Shortest Process Next.

SJF (or SPN) can starve a process that requires a long burst.

Starvation can be prevented by the standard technique.

Question: What is that technique?

Answer: Priority aging (see below).

Preemptive version of above. Indeed some authors call it preemptive shortest job first.

Permit a process that enters the ready list to preempt the running process if the time for the new process (or for its next burst) is less than the remaining time for the running process (or for its current burst).

It will never happen that a process already in the ready list

will require less time than the remaining time for the currently

running process.

Why?

Answer: When the process joined the ready list

it would have started running if the current process had more

time remaining.

Since that didn't happen the currently running job had less time

remaining and now it has even less.

SRTN Can starve a process that requires a long burst.

Starvation can be prevented by the standard technique.

Question: What is that technique?

Answer: Priority aging (see below).

The following algorithms can also be used for batch systems, but in that case, the gain may not justify the extra complexity.

Round Robin (RR) is an important preemptive policy. It is essentially the preemptive version of FCFS. The idea is to approximate SJF without knowing in advance how long the job will require.