Operating Systems

Start Lecture #7

6.5: Deadlock Avoidance

Let's see if we can tiptoe through the tulips and avoid deadlock

states even though our system does permit all four of the necessary

conditions for deadlock.

An optimistic resource manager is one that grants every

request as soon as it can.

To avoid deadlocks with all four conditions present, the manager

must be smart not optimistic.

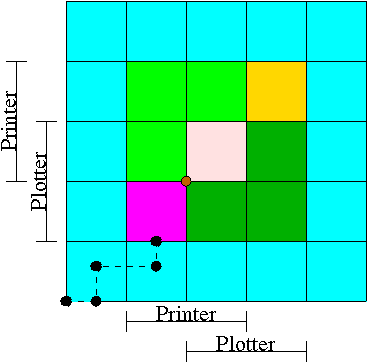

6.5.1 Resource Trajectories

We plot progress of each process along an axis.

In the example we show, there are two processes, hence two axes,

i.e., planar.

This procedure assumes that we know the entire request and release

pattern of the processes in advance so it is not a

practical solution.

I present it as it is some motivation for the practical solution

that follows, the Banker's Algorithm.

- We have two processes H (horizontal) and V.

- The origin represents them both starting.

- Their combined state is a point on the graph.

- The parts where the printer and plotter are needed by each process

are indicated.

- The dark green is where both processes have the plotter and hence

execution cannot reach this point.

- Light green represents both having the printer; also impossible.

- Pink is both having both printer and plotter; impossible.

- Gold is possible (H has plotter, V has printer), but the system

can't get there.

- The upper right corner is the goal; both processes have finished.

- The brown dot is ... (cymbals) deadlock.

We don't want to go there.

- The cyan is safe.

From anywhere in the cyan we have horizontal and vertical moves to

the finish point (the upper right corner) without hitting any

impossible area.

- The magenta interior is very interesting.

It is

- Possible: each processor has a different resource.

- Not deadlocked: each processor can move within the magenta.

- Deadly: deadlock is unavoidable.

You will hit a magenta-green boundary and then will no choice

but to turn and go to the brown dot.

- The cyan-magenta border is the danger zone.

- The dashed line represents a possible execution pattern.

- With a uniprocessor no diagonals are possible.

We either move to the right meaning H is executing or move up

indicating V is executing.

- The trajectory shown represents.

- H excuting a little.

- V excuting a little.

- H executes; requests the printer; gets it; executes some more.

- V executes; requests the plotter.

- The crisis is at hand!

- If the resource manager gives V the plotter, the magenta has been

entered and all is lost.

Abandon all hope ye who enter here

—Dante.

- The right thing to do is to deny the request, let H execute

move horizontally under the magenta and dark green.

At the end of the dark green, no danger remains, both processes

will complete successfully.

Victory!

- This procedure is not practical for a general purpose OS since

it requires knowing the programs in advance.

That is, the resource manager, knows in advance what requests each

process will make and in what order.

Homework:

All the trajectories in Figure 6-8 are horizontal or vertical.

Is is possible for a trajectory to be a diagonal.

Homework: 11, 12.

6.5.2 Safe States

Avoiding deadlocks given some extra knowledge.

-

Not surprisingly, the resource manager knows how many units of each

resource it had to begin with.

- Also it knows how many units of each resource it has given to

each process.

- It would be great to see all the programs in advance and thus know

all future requests, but that is asking for too much.

- Instead, when each process starts, it announces its maximum usage.

That is each process, before making any resource requests, tells

the resource manager the maximum number of units of each resource

the process can possible need.

This is called the claim of the process.

- If the claim is greater than the total number of units in the

system the resource manager kills the process when receiving

the claim (or returns an error code so that the process can

make a new claim).

- If during the run the process asks for more than its claim,

the process is aborted (or an error code is returned and no

resources are allocated).

- If a process claims more than it needs, the result is that the

resource manager will be more conservative than need be and there

will be more waiting.

Definition: A state is

safe if there is an ordering of the processes such

that: if the processes are run in this order, they will all

terminate (assuming none exceeds its claim and assuming each would

terminate if all its requests are granted).

Recall the comparison made above between detecting deadlocks (with

multi-unit resources) and the banker's algorithm (which stays in

safe states).

- The deadlock detection algorithm given makes the most

optimistic assumption

about a running process: it will return all its resources and

terminate normally.

If we still find processes that remain blocked, they are

deadlocked.

- The banker's algorithm makes the most pessimistic

assumption about a running process: it immediately asks for all

the resources it can (i.e., up to its initial claim).

If, even with such demanding processes, the resource manager can

assure that all process terminates, then we can ensure that

deadlock is avoided.

In the definition of a safe state no assumption is made about the

running processes.

That is, for a state to be safe, termination must occur no matter

what the processes do (providing each would terminate if run alone

and each never exceeds its claims).

Making no assumption on a process's behavior is the same as making

the most pessimistic assumption.

Remark: When I say pessimistic

I am

speaking from the point of view of the resource manager.

From the manager's viewpoint, the worst thing a process can do is

request resources.

Give an example of each of the following four possibilities.

A state that is

- Safe and deadlocked—not possible.

- Safe and not deadlocked—a trivial is example is a graph with

no arcs.

- Not safe and deadlocked—easy (any deadlocked state).

- Not safe and not deadlocked—interesting.

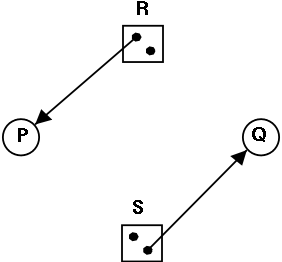

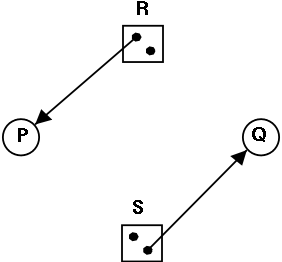

Is the figure on the right safe or not?

Is the figure on the right safe or not?

- You can NOT tell until I give you the initial

claims of the process.

- Please do not make the unfortunately common exam mistake to

give an example involving safe states without giving the

claims.

So if I ask you to draw a resource allocation graph that is

safe or if I ask you to draw one that is unsafe, you

MUST include the initial claims for each

process.

I often, but not always, ask such a question

and every time I have done so, several

students forgot to give the claims and hence lost points.

- For the figure on the right, if the initial claims are:

P: 1 unit of R and 2 units of S (written (1,2))

Q: 2 units of R and 1 units of S (written (2,1))

the state in the figure is NOT safe.

- But if the initial claims are instead:

P: 2 units of R and 1 units of S (written (2,1))

Q: 1 unit of R and 2 units of S (written (1,2))

the state in the figure IS safe.

- Explain why this is so.

A manager can determine if a state is safe.

- Since the manager know all the claims, it can determine the

maximum amount of additional resources each process can request.

- The manager knows how many units of each resource it has left.

The manager then follows the following procedure, which is part of

Banker's Algorithms discovered by Dijkstra, to

determine if the state is safe.

-

If there are no processes remaining, the state is

safe.

- Seek a process P whose maximum additional request for each

resource type is less than what remains for that resource type.

- If no such process can be found, then the state is

not safe.

- If such a P can be found, the banker (manager) knows that

if it refuses all requests except those from P, then it

will be able to satisfy all of P's requests.

Why?

Ans: Look at how P was chosen.

- The banker now pretends that P has terminated (since the

banker knows that it can guarantee this will happen).

Hence the banker pretends that all of P's currently held

resources are returned.

This makes the banker richer and hence perhaps a process that

was not eligible to be chosen as P previously, can now be

chosen.

- Repeat these steps.

Example 1

Consider the example shown in the table on the right.

A safe state with 22 units of one resource

| process | initial claim | current alloc | max add'l |

|---|

| X | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Y | 11 | 5 | 6 |

| Z | 19 | 10 | 9 |

| Total | 16 |

| Available | 6 |

- One resource type R with 22 unit.

- Three processes X, Y, and Z with initial claims 3, 11, and 19

respectively.

- Currently the processes have 1, 5, and 10 units respectively.

- Hence the manager currently has 6 units left.

- Also note that the max additional needs for the processes are 2,

6, and 9 respectively.

- So the manager cannot assure (with its current

remaining supply of 6 units) that Z can terminate.

But that is not the question.

-

This state is safe.

- Use 2 units to satisfy X; now the manager has 7 units.

- Use 6 units to satisfy Y; now the manager has 12 units.

- Use 9 units to satisfy Z; done!

Example 2

This example is a continuation of example 1 in which Z requested 2

units and the manager (foolishly?) granted the request.

An unsafe state with 22 units of one resource

| process | initial claim | current alloc | max add'l |

|---|

| X | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Y | 11 | 5 | 6 |

| Z | 19 | 12 | 7 |

| Total | 18 |

| Available | 4 |

- Currently the processes have 1, 5, and 12 units respectively.

- The manager has 4 units.

- The max additional needs are 2, 6, and 7.

- This state is unsafe

- X is the only process whose maximum additional request can

be satisfied at this point.

- So use 2 unit to satisfy X; now the manager has 5 units.

- Y needs 6 and Z needs 7 and we can't guarantee satisfying

either request.

- Note that we were able to find a process (X)

that can terminate, but then we were stuck.

So it is not enough to find one process.

We must find a sequence of all the processes.

Remark: An unsafe state is not necessarily

a deadlocked state.

Indeed, for many unsafe states, if the manager gets lucky all

processes will terminate successfully.

Processes that are not currently blocked can terminate (instead of

requesting more resources up to their initial claim, which is the

worst case and is the case the manager prepares for).

A safe state means that the manager can guarantee

that no deadlock will occur (even in the worst case in which

processes request as much as permitted by their initial claims.)

6.5.3 The Banker's Algorithm (Dijkstra) for a Single Resource

The algorithm is simple: Stay in safe states.

For now, we assume that, before execution begins, all processes

are present and all initial claims have been given.

We will relax these assumptions very soon.

In a little more detail the banker's algorithm is as follows.

- Before execution begins, ensure that the system is safe.

That is, check that no process claims more than the manager

has.

If not, then the offending process is trying to claim more of

some resource than exists in the system has and hence cannot be

guaranteed to complete even if run by itself.

You might say that it can become deadlocked all by

itself.

The only thing the manager can do is to refuse to acknowledge

the existence of the offending process.

- When the manager receives a request, it

pretends to grant it, and then checks if the

resulting state is safe.

If it is safe, the request is really granted; if it is not safe

the process is blocked (that is, the request is held

up).

- When a resource is returned, the manager (politely thanks the

process and then) checks to see if the first pending

requests can be granted (i.e., if the result would now be safe).

If so the pending request is granted.

Whether or not the request was granted, the manager checks to

see if the next pending request can be granted, etc.

Homework: 16.

6.5.4 The Banker's Algorithm for Multiple Resources

At a high level the algorithm is identical to the one for a single

resource type: Stay in safe states.

But what is a safe state in this new setting?

The same definition (if processes are run in a certain order they

will all terminate).

Checking for safety is the same idea as above.

The difference is that to tell if there are enough free resources

for a processes to terminate, the manager must check that

for all resource types, the number of free units is

at least equal to the max additional need of the process.

Homework: Consider a system containing a total of

12 units of resource R and 24 units of resource S managed by the

banker's algorithm.

There are three processes P1, P2, and P3.

P1's claim is 0 units of R and 12 units of S, written (0,12).

P2's claim is (8,15).

P3's claim is (8,20).

Currently P1 has 4 units of S, P2 has 8 units of R, P3 has 8 units

of S, and there are no outstanding requests.

- What is the largest number of units of S that P1 can request

at this point that the banker will grant?

- If P2 instead of P1 makes the request, what is the largest

number of units of S that the banker will grant?

- If P3 instead of P1 or P2 makes the request, what is the

largest number of units of S that the banker will grant?

Remark: Remind me to go over this one next

time.

Limitations of the Banker's Algorithm

- Often users don't know the maximum requests a process will make.

They can estimate conservatively (i.e., use big numbers for the claim)

but then the manager becomes very conservative.

- New processes arriving cause a problem (but not so bad as

Tanenbaum suggests).

- The process's claim must be less than the total number of

units of the resource in the system.

If not, the process is not accepted by the manager.

- Since the state without the new process is safe, so is the

state with the new process!

Just use the process order the banker had originally and put

the new process at the end.

- Insuring fairness (starvation freedom) needs a little more

work, but isn't too hard either (once an hour stop taking new

processes until all current processes finish).

- A resource can become unavailable (e.g., a CD-ROM drive might

break).

This can result in an unsafe state and deadlock.

Homework: 22, 25, and 30.

There is an interesting typo in 22.

A has claimed 3 units of resource 5, but there are only 2 units in

the entire system.

Change the problem by having B both claim and be allocated 1 unit of

resource 5.

6.7 Other Issues

6.7.1 Two-phase locking

This is covered (MUCH better) in a database text.

We will skip it.

6.7.2 Communication Deadlocks

We have mostly considered actually hardware resources such as

printers, but have also considered more abstract resources such as

semaphores.

There are other possibilities.

For example a server often waits for a client to make a request.

But if the request msg is lost the server is still waiting for the

client and the client is waiting for the server to respond to the

(lost) last request.

Each will wait for the other forever, a deadlock.

A solution

to this communication deadlock would be to use a

timeout so that the client eventually determines that the msg was

lost and sends another.

But it is not nearly that simple:

The msg might have been greatly delayed and now the server will get

two requests, which could be bad, and is likely to send two replies,

which also might be bad.

This gives rise to the serious subject of communication

protocols.

6.7.3 Livelock

Instead of blocking when a resource is not available, a process may

(wait and then) try again to obtain it.

Now assume process A has the printer, and B the CD-ROM, and each

process wants the other resource as well.

A will repeatedly request the CD-ROM and B will repeatedly request the

printer.

Neither can ever succeed since the other process holds the desired

resource.

Since no process is blocked, this is not technically deadlock, but a

related concept called livelock.

6.7.4 Starvation

As usual FCFS is a good cure.

Often this is done by priority aging and picking the highest

priority process to get the resource.

Also can periodically stop accepting new processes until all old

ones get their resources.

6.8 Research on Deadlocks

6.9 Summary

Read.

Remark: Lab 3 (banker) assigned; due 29 March 2011.

Chapter 3 Memory Management

Also called storage management or

space management.

The memory manager must deal with the

storage hierarchy present in modern machines.

- The hierarchy consists of registers (the highest level),

cache, central memory, disk, tape (backup).

- Various (hardware and software) memory managers moves data

from level to level of the hierarchy.

- We are concerned with the central memory ↔ disk boundary.

- The same questions are asked about the cache ↔ central

memory boundary when one studies computer architecture.

Surprisingly, the terminology is almost completely different!

- When should we move data up to a higher level?

- Fetch on demand (e.g. demand paging, which is dominant now

and which we shall study in detail).

- Prefetch

- Read-ahead for file I/O.

- Large cache lines and pages.

- Extreme example.

Entire job present whenever running.

- Unless the top level has sufficient memory for the entire

system, we must also decide when to move data down to a lower

level.

This is normally called evicting the data (from the higher

level).

- In OS classes we concentrate on the central-memory/disk layers

and transitions.

- In architecture we concentrate on the cache/central-memory

layers and transitions (and use different terminology).

We will see in the next few weeks that there are three independent

decision:

- Should we have segmentation.

- Should we have paging.

- Should we employ fetch on demand.

Memory management implements address translation.

- Convert virtual addresses to physical addresses

- Also called logical to real address translation.

- A virtual address is the address expressed in

the program.

- A physical address is the address understood

by the computer hardware.

- The translation from virtual to physical addresses is performed by

the Memory Management Unit or (MMU).

- Another example of address translation is the conversion of

relative addresses to absolute addresses

by the linker.

- The translation might be trivial (e.g., the identity) but not

in a modern general purpose OS.

- The translation might be difficult (i.e., slow).

- Often includes addition/shifts/mask—not too bad.

- Often includes memory references.

- VERY serious.

- Solution is to cache translations in a

Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB).

Sometimes called a translation buffer (TB).

Homework:

What is the difference between a physical address and a virtual address?

Is the figure on the right safe or not?

Is the figure on the right safe or not?