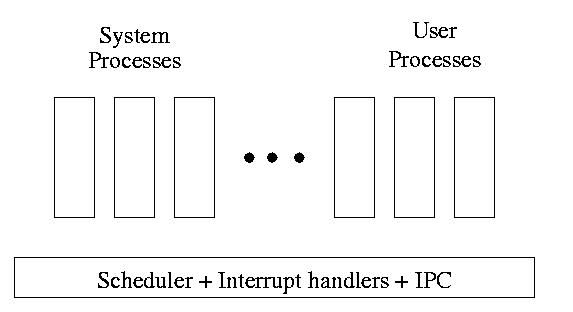

One can organize an OS around the scheduler.

One can organize an OS around the scheduler.

Start Lecture #3

One can organize an OS around the scheduler.

One can organize an OS around the scheduler.

kernel(a micro-kernel) consisting of the scheduler, interrupt handlers, and IPC (interprocess communication).

Minixoperating system works this way.

The OS organizes the data about each process in a table naturally called the process table. Each entry in this table is called a process table entry or process control block (PCB).

(I have often referred to a process table entry as a PTE, but this is bad since I also use PTE for Page Table Entry. Because the latter usage is very common, I must stop using PTE to abbreviate the former. Please correct me if I slip up.)

Characteristics of the process table.

an active entity becomes a data structure when looked at from a lower level.

This should be compared with the addenda on transfer of control and trap.

In a well defined location in memory (specified by the hardware) the OS stores an interrupt vector, which contains the address of the interrupt handler.

Assume a process P is running and a disk interrupt occurs for the completion of a disk read previously issued by process Q, which is currently blocked. Note that disk interrupts are unlikely to be for the currently running process (because the process that initiated the disk access is likely blocked).

this instruction caused the interrupt.

program, namely the OS, and hence might well be using the same variables. We will soon see how this can cause great problems even in what appear to be trivial cases.

Consider a job that is unable to compute (i.e., it is waiting for I/O) a fraction p of the time.

There are at least two causes of inaccuracy in the above modeling procedure.

Nonetheless, it is correct that increasing MPL does increase CPU utilization up to a point.

An important limitation is memory. That is, we assumed that we have many jobs loaded at once, which means we must have enough memory for them. There are other memory-related issues as well and we will discuss them later in the course.

Homework: 5.

| Per process items | Per thread items |

|---|---|

| Address space | Program counter |

| Global variables | Machine registers |

| Open files | Stack |

| Child processes | |

| Pending alarms | |

| Signals and signal handlers | |

| Accounting information |

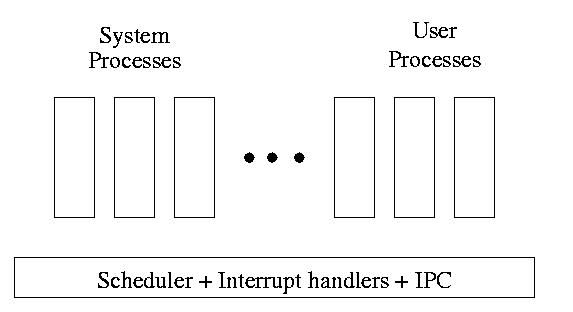

The idea behind threads to have separate threads of control (hence the name) running in the address space of a single process as shown in the diagram to the right. An address space is a memory management concept. For now think of an address space as the memory in which a process runs. (In reality it also includes the mapping from virtual addresses, i.e., addresses in the program, to physical addresses, i.e., addresses in the machine. The table on the left shows which properties are common to all threads in a given process and which properties are thread specific.

Each thread is somewhat like a process (e.g., it shares the processor with other threads) but a thread contains less state than a process (e.g., the address space belongs to the process in which the thread runs.)

Often, when a process P executing an application is blocked (say for I/O), there is still computation that can be done for the application. Another process can't do this computation since it doesn't have access to P's memory. But two threads in the same process do share memory so that problem doesn't occur.

An important modern example is a multithreaded web server.

Each thread is responding to a single WWW connection.

While one thread is blocked on I/O, another thread can be processing

another WWW connection.

Question: Why not use separate processes, i.e.,

what is the shared memory?

Answer: The cache of frequently referenced pages.

A common organization for a multithreaded application is to have a dispatcher thread that fields requests and then passes each request on to an idle worker thread. Since the dispatcher and worker share memory, passing the request is very low overhead.

Another example is a producer-consumer problem (see below) in which we have 3 threads in a pipeline. One thread reads data from an I/O device into an input buffer, the second thread performs computation on the input buffer and places results in an output buffer, and the third thread outputs the data found in the output buffer. Again, while one thread is blocked the others can execute.

Really you want 2 (or more) input buffers and 2 (or more) output buffers. Otherwise the middle thread would be using all the buffers and would block both outer threads.

Question: When does each thread block?

Answer:

A final (related) example is that an application wishing to perform automatic backups can have a thread to do just this. In this way the thread that interfaces with the user is not blocked during the backup. However some coordination between threads may be needed so that the backup is of a consistent state.

A process contains a number of resources such as address space, open files, accounting information, etc. In addition to these resources, a process has a thread of control, e.g., program counter, register contents, stack. The idea of threads is to permit multiple threads of control to execute within one process. This is often called multithreading and threads are sometimes called lightweight processes. Because threads in the same process share so much state, switching between them is much less expensive than switching between separate processes.

Individual threads within the same process are not completely independent. For example there is no memory protection between them. This is typically not a security problem as the threads are cooperating and all are from the same user (indeed the same process). However, the shared resources do make debugging harder. For example one thread can easily overwrite data needed by another thread in the process and when the second thread fails, the cause may be hard to determine because the tendency is to assume that the failed thread caused the failure.

A new thread in the same process is created by a routine named something like thread_create; similarly there is thread_exit. The analogue to waitpid is thread_join (the name comes presumably from the fork-join model of parallel execution).

The routine tread_yield, which relinquishes the processor, does not have a direct analogue for processes. The corresponding system call (if it existed) would move the process from running to ready.

Homework: 11.

Assume a process has several threads. What should we do if one of these threads

POSIX threads (pthreads) is an IEEE standard specification that is supported by many Unix and Unix-like systems. Pthreads follows the classical thread model above and specifies routines such as pthread_create, pthread_yield, etc.

An alternative to the classical model are the so-called Linux threads (see the section 10.3 in the 3e).

Write a (threads) library that acts as a mini-scheduler and implements thread_create, thread_exit, thread_wait, thread_yield, etc. This library acts as a run-time system for the threads in this process. The central data structure maintained and used by this library is a thread table, the analogue of the process table in the operating system itself.

There is a thread table and an instance of the threads library in each multithreaded process.

Advantages of User-Mode Threads

:

Disadvantages

For a uniprocessor, which is all we are officially considering, there is little gain in splitting pure computation into pieces. If the CPU is to be active all the time for all the threads, it is simpler to just have one (unithreaded) process.

But this changes for multiprocessors/multicores. Now it is very useful to split computation into threads and have each executing on a separate processor/core. In this case, user-mode threads are wonderful, there are no system calls and the extremely low overhead is beneficial.

However, there are serious issues involved is programming applications for this environment.

One can move the thread operations into the operating system itself. This naturally requires that the operating system itself be (significantly) modified and is thus not a trivial undertaking.

One can write a (user-level) thread library even if the kernel also has threads. This is sometimes called the N:M model since N user-mode threads run on M kernel threads. In this scheme, the kernel threads cooperate to execute the user-level threads.

An offshoot of the N:M terminology is that kernel-level threading (without user-level threading) is sometimes referred to as the 1:1 model since one can think of each thread as being a user level thread executed by a dedicated kernel-level thread.

Homework: 12, 14.

Skipped

The idea is to automatically issue a thread-create system call upon message arrival. (The alternative is to have a thread or process blocked on a receive system call.) If implemented well, the latency between message arrival and thread execution can be very small since the new thread does not have state to restore.

Definitely NOT for the faint of heart.

Remark: We shall do section 2.4 before section 2.3 for two reasons.

Scheduling processes on the processor is often called

processor scheduling

or process scheduling

or

simply scheduling

.

As we shall see later in the course, a more descriptive name would

be short-term, processor scheduling

.

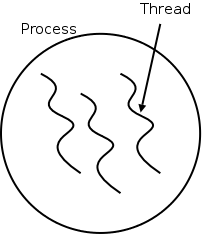

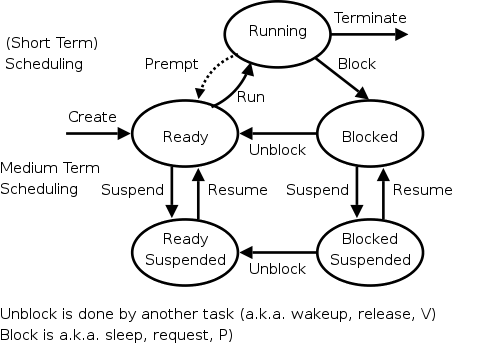

For now we are discussing the arcs connecting running↔ready in the diagram on the right showing the various states of a process. Medium term scheduling is discussed later as is disk-arm scheduling.

Naturally, the part of the OS responsible for (short-term, processor) scheduling is called the (short-term, processor) scheduler and the algorithm used is called the (short-term, processor) scheduling algorithm.

Early computer systems were monoprogrammed and, as a result, scheduling was a non-issue.

For many current personal computers, which are definitely multiprogrammed, there is in fact very rarely more than one runnable process. As a result, scheduling is not critical.

For servers (or old mainframes), scheduling is indeed important and these are the systems you should think of.

Processes alternate CPU bursts with I/O activity, as we shall see in lab2. The key distinguishing factor between compute-bound (aka CPU-bound) and I/O-bound jobs is the length of the CPU bursts.

The trend over the past decade or two has been for more and more jobs to become I/O-bound since the CPU rates have increased faster than the I/O rates.

An obvious point, which is often forgotten (I don't think 3e mentions it) is that the scheduler cannot run when the OS is not running. In particular, for the uniprocessor systems we are considering, no scheduling can occur when a user process is running. (In the mulitprocessor situation, no scheduling can occur when all processors are running user jobs).

Again we refer to the state transition diagram above.

It is important to distinguish preemptive from non-preemptive scheduling algorithms.

run until completion, yield, or block.

preemptarc in the diagram is present for preemptive scheduling algorithms.

We distinguish three categories of scheduling algorithms with regard to the importance of preemption.

For multiprogramed batch systems (we don't consider uniprogrammed systems, which don't need schedulers) the primary concern is efficiency. Since no user is waiting at a terminal, preemption is not crucial and if it is used, each process is given a long time period before being preempted.

For interactive systems (and multiuser servers), preemption is crucial for fairness and rapid response time to short requests.

We don't study real time systems in this course, but can say that preemption is typically not important since all the processes are cooperating and are programmed to do their task in a prescribed time window.

There are numerous objectives, several of which conflict, that a scheduler tries to achieve. These include.

more importantprocesses higher priority. For example, if my laptop is trying to fold proteins in the background, I don't want that activity to appreciably slow down my compiles and especially don't want it to make my system seem sluggish when I am modifying these class notes. In general,

interactivejobs should have higher priority.

jobto its termination. This is important for batch jobs.

shortest job first.

wasted cyclesand limited logins for repeatability.

This is used for real time systems. The objective of the scheduler is to find a schedule for all the tasks (there are a fixed set of tasks) so that each meets its deadline. The run time of each task is known in advance.

Actually it is more complicated.

There is an amazing inconsistency in naming the different (short-term) scheduling algorithms. Over the years I have used primarily 4 books: In chronological order they are Finkel, Deitel, Silberschatz, and Tanenbaum. The table just below illustrates the name game for these four books. After the table we discuss several scheduling policy in some detail.

Finkel Deitel Silbershatz Tanenbaum

-------------------------------------

FCFS FIFO FCFS FCFS

RR RR RR RR

PS ** PS PS

SRR ** SRR ** not in tanenbaum

SPN SJF SJF SJF

PSPN SRT PSJF/SRTF SRTF

HPRN HRN ** ** not in tanenbaum

** ** MLQ ** only in silbershatz

FB MLFQ MLFQ MQ

Remark: For an alternate organization of the scheduling algorithms (due to my former PhD student Eric Freudenthal and presented by him Fall 2002) click here.

If the OS doesn't

schedule, it still needs to store the list

of ready processes in some manner.

If it is a queue you get FCFS.

If it is a stack (strange), you get LCFS.

Perhaps you could get some sort of random policy as well.