Start Lecture #24

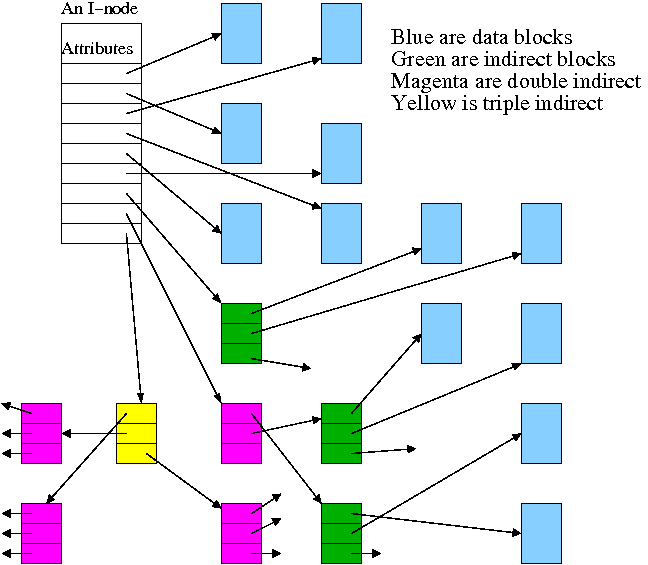

Continuing the idea of adapting storage schemes from other regimes to file storage, why don't we mimic the idea of (non-demand) paging and have a table giving, for each block of the file, where on the disk that file block is stored? In other words a ``file block table'' mapping each file block to its corresponding disk block. This is the idea of (the first part of) the unix i-node solution, which we study next.

Although Linux and other Unix and Unix-like operating systems have a variety of file systems, the most widely used Unix file systems are i-node based as was the original Unix file system from Bell Labs.

There is some question of what the i

stands for.

The consensus seems to be index.

Now, however, people often write inode (not i-node) and don't view the

i

as standing for anything.

Inode based systems have the following properties.

Given a block number (byte number / block size), how do you find the block?

Specifically assume

firstblock.

If N < D // This is a direct block in the i-node

use direct pointer N in the i-node

else if N < D + K // The single indirect block has a pointer to this block

use pointer D in the inode to get the indirect block

the use pointer N-D in the indirect block to get block N

else // This is one of the K*K blocks obtained via the double indirect block

use pointer D+1 in the inode to get the double indirect block

let P = (N-(D+K)) DIV K // Which single indirect block to use

use pointer P to get the indirect block B

let Q = (N-(D+K)) MOD K // Which pointer in B to use

use pointer Q in B to get block N

For example, let D=12, assume all blocks are 1000B, assume all pointers are 4B. Retrieve the block containing byte 1,000,000.

With a triple indirect block, the ideas are the same, but there is more work.

Homework: Consider an inode-based system with the same parameters as just above, D=12, K=250, etc.

End of Problem

Recall that the primary function of a directory is to map the file name (in ASCII, Unicode, or some other text-based encoding) to whatever is needed to retrieve the data of the file itself.

There are several ways to do this depending on how files are stored.

Another important function is to enable the retrieval of the various attributes (e.g., length, owner, size, permissions, etc.) associated with a given file.

Homework: 25

It is convenient to view the directory as an array of entries, one per file. This view tacitly assumes that all entries are the same size and, in early operating systems, they were. Most of the contents of a directory are inherently of a fixed size. The primary exception is the file name.

Early systems placed a severe limit on the maximum length of a file name and allocated this much space for all names. DOS used an 8+3 naming scheme (8 characters before the dot and 3 after). Unix version 7 limited names to 14 characters.

Later systems raised the limit considerably (255, 1023, etc) and thus allocating the maximum amount for each entry was inefficient and other schemes were used. Since we are storing variable size quantities, a number of the consideration that we saw for non-paged memory management arise here as well.

The simple scheme is to search the list of directory entries linearly, when looking for an entry with a specific file name. This scheme becomes inefficient for very large directories containing hundreds or thousands of files. In this situation a more sophisticated technique (such as hashing or B-trees) is used.

We often think of the files and directories in a file system as forming a tree (or forest). However in most modern systems this is not necessarily the case, the same file can appear in two different directories (not two copies of the file, but the same file). It can also appear multiple times in the same directory, having different names each time.

I like to say that the same file has two different names. One can also think of the file as being shared by the two directories (but those words don't work so well for a file with two names in the same directory).

Sharedfiles is Tanenbaum's terminology.

With unix hard links there are multiple names for the same file and each name has equal status. The directory entries for both names point to the same inode.

real nameand the other one is

just a link.

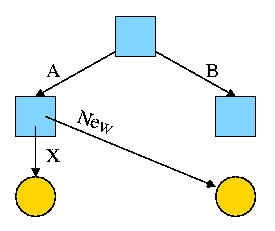

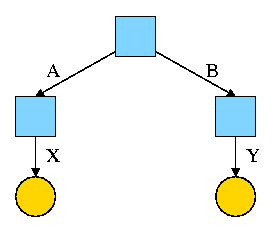

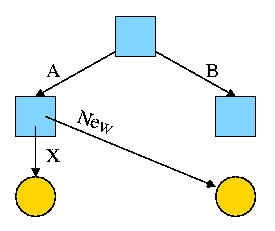

For example, the diagram on the right illustrates the result that occurs when, starting with an empty file system (i.e., just the root directory) one executes

cd /

mkdir /A; mkdir /B

touch /A/X; touch /B/Y

The diagrams in this section use the following conventions

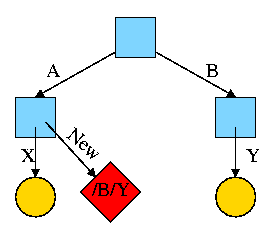

Now we execute

ln /B/Y /A/New

which leads to the next diagram on the right.

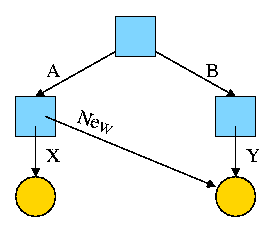

At this point there are two equally valid name for the right hand yellow file, /B/Y and /A/New. The fact that /B/Y was created first is NOT detectable.

the file nameS(plural) vs

the file(singular).

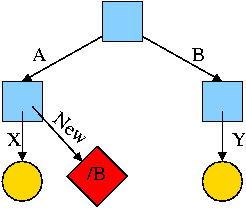

Assume Bob created /B and /B/Y and Alice created /A, /A/X, and /A/New. Later Bob tires of /B/Y and removes it by executing

rm /B/Y

The file /A/New is still fine (see third diagram on the right). But it is owned by Bob, who can't find it! If the system enforces quotas Bob will likely be charged (as the owner), but he can neither find nor delete the file (since Bob cannot unlink, i.e. remove, files from /A).

If, prior to removing /B/Y, Bob had examined its link count

(an attribute of the file),

he would have noticed that there is another (hard) link to the file,

but would not have been able to determine in which directory (/A in

this case) the hard link was located or what is the name of the file

in that directory (New in this case).

Since hard links are only permitted to files (not directories) the resulting file system is a dag (directed acyclic graph). That is, there are no directed cycles. We will now proceed to give away this useful property by studying symlinks, which can point to directories.

As just noted, hard links do NOT create a new file, just another name for an existing file. Once the hard link is created the two names have equal status.

Symlinks, on the other hand DO create another file, a non-regular file, that itself serves as another name for the original file. Specifically

Again start with an empty file system and this time execute the following code sequence (the only difference from the above is the addition of a -s).

cd /

mkdir /A; mkdir /B

touch /A/X; touch /B/Y

ln -s /B/Y /A/New

We now have an additional file /A/New, which is a symlink to /B/Y.

/B/Y).

The bottom line is that, with a hard link, a new name is created for the file. This new name has equal status with the original name. This can cause some surprises (e.g., you create a link but I own the file). With a symbolic link a new file is created (owned by the creator naturally) that contains the name of the original file. We often say the new file points to the original file.

Question: Consider the hard link setup above.

If Bob removes /B/Y and then creates another /B/Y, what happens to

/A/New?

Answer: Nothing.

/A/New is still a file owned by Bob having the same

contents, creation time, etc. as the original /B/Y.

Question: What about with a symlink?

Answer: /A/New becomes invalid and then valid again, this time pointing

to the new /B/Y.

(It can't point to the old /B/Y as that is completely gone.)

Note:

Shortcuts in windows contain more than symlinks contain in unix.

In addition to the file name of the original file, they can contain

arguments to pass to the file if it is executable.

So a shortcut to

firefox.exe

can specify

firefox.exe //cs.nyu.edu/~gottlieb/courses/os/class-notes.html

Moreover, as was pointed out by students in my 2006-07 fall class,

the shortcuts are not a feature of the windows FAT file system

itself, but simply the actions of the command interpreter when

encountering a file named *.lnk

End of Note.

What happens if the target of the symlink is an existing directory? For example, consider the code below, which gives rise to the diagram on the right.

cd /

mkdir /A; mkdir /B

touch /A/X; touch /B/Y

ln -s /B /A/New

This research project of the early 1990s was inspired by the key observation that systems are becoming limited in speed by small writes. The factors contributing to this phenomenon were (and still are).

preparationbefore any data is transferred, and then can transfer a block in less than 1ms. Thus, a one block

transferspends most of its time

getting readyto transfer.

The goal of the log-structured file system project was to design a file system in which all writes are large and sequential (most of the preparation is eliminated when writes are sequential). These writes can be thought of as being appended to a log, which gave the project its name.

cleanerprocess runs in the background and examines segments starting from the beginning. It removes overwritten blocks and then adds the remaining blocks to the segment buffer. (This is very much not trivial.)

Despite the advantages given, log-structured file systems have not caught on. They are incompatible with existing file systems and the cleaner has proved to be difficult.