Start Lecture #6

Homework: Compute FIRST and FOLLOW for the postfix grammar S → S S + | S S * | a

The predictive parsers of chapter 2 are recursive descent parsers needing no backtracking. A predictive parser can be constructed for any grammar in the class LL(1). The two Ls stand for processing the input Left to right and for producing Leftmost derivations. The 1 in parens indicates that 1 symbol of lookahead is used.

Definition: A grammar is LL(1) if for all production pairs A → α | β

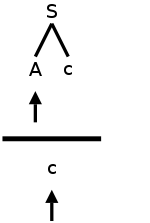

The 2nd condition may seem strange; it did to me for a while. Let's consider the simplest case that condition 2 is trying to avoid. S is the start symbol

A → ε // β=ε so β derives ε

A → c // α=c so α derives a string beginning with c

S → A c // c is in FOLLOW(A)

Probably the simplest derivation possible is

S ⇒ A c ⇒ c

Assume we are using predictive parsing and, as illustrated in the diagram to the right, we are at A in the parse tree and c in the input. Since lookahead=c and c is in FIRST(RHS) for the second A production, we would choose that production to expand A. But this is wrong! Remember that we don't look ahead in the tree, we look ahead just in the input. So we would not have noticed that the next node in the tree (i.e., in the frontier) is c. The next node can indeed be c since c is in FOLLOW(A). So we should have used the top A production to produce ε in the tree, and then the next node c would match the input c.

The goal is to produce a table telling us at each situation which

production to apply.

A situation

means a nonterminal in the parse tree and an

input symbol in lookahead.

So we produce a table with rows corresponding to nonterminals and columns corresponding to input symbols (including $, the endmarker). In an entry we put the production to apply when we are in that situation.

We start with an empty table M and populate it as follows. (2e has typo; it has FIRST(A) instead of FIRST(α).) For each production A → α

strange) condition above. If ε is in FIRST(α), then α⇒*ε. Hence we could (should??) apply the production A→α, have the α go to ε and then the b (or $) that follows A will match the b in the input.

When we have finished filling in the table M, what do we do if an slot has

LL(1) grammars. Mostly likely the problem is that the grammar is not LL(1). (Also possible is that an error was made in constructing the table.) Since the grammar is not LL(1), we must use a different technique instead of predictive parsing. One possibility is bottom-up parsing, which we study next. Another possibility is to modify the procedure for this non-terminal to look further ahead (typically one more token) to decide what action to perform.

Example: Work out the parsing table for

E → T E'

E' → + T E' | ε

T → F T'

T' → * F T' | ε

F → ( E ) | id

We already computed FIRST and FOLLOW as shown on the right. The table skeleton is

| FIRST | FOLLOW | |

|---|---|---|

| E | ( id | $ ) |

| E' | ε + | $ ) |

| T | ( id | + $ ) |

| T' | ε * | + $ ) |

| F | ( id | * + $ ) |

| Nonter- minal | Input Symbol | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | * | ( | ) | id | $ | |

| E | ||||||

| E' | ||||||

| T | ||||||

| T' | ||||||

| F | ||||||

Example: What about ε-productions? Produce FIRST, FOLLOW, and the parsing table for

S → B D

B → b | ε

D → d | ε

Homework: Produce the predictive parsing table for

Remark: Lab 3 will use the material up to here.

This illustrates the standard technique for eliminating recursion by keeping the stack explicitly. The runtime improvement can be considerable.

Now we start with the input string, i.e., the bottom (leaves) of what will become the parse tree, and work our way up to the start symbol.

For bottom up parsing, we are not fearful of left recursion as we were with top down. Our first few examples will use the left recursive expression grammar

E → E + T | T

T → T * F | F

F → ( E ) | id

Remember that running a production in reverse

, i.e., replacing

the RHS by the LHS, is called reducing.

So our goal is to reduce the input string to the start symbol.

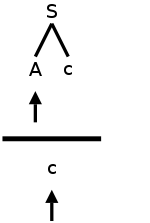

On the right is a movie of parsing id*id in a bottom-up fashion. Note the way it is written. For example, from step 1 to 2, we don't just put F above id*id. We draw it as we do because it is the current top of the tree (really forest) and not the bottom that we are working on so we want the top to be in a horizontal line and hence easy to read.

The tops of the forest are the roots of the subtrees present in the diagram. For the movie those are

id * id, F * id, T * id, T * F, T, E

Note that (since the reduction successfully reaches the start

symbol) each of these sets of roots is a sentential form.

The steps from one frame of the movie, when viewed going down the

page, are reductions (replace the RHS of a production by the LHS).

Naturally, when viewed going up the page, we have a derivation

(replace LHS by RHS).

For our example the derivation is

E ⇒ T ⇒ T * F ⇒

T * id ⇒ F * id ⇒ id * id

Note that this is a rightmost derivation and hence each of the sets of roots identified above is a right sentential form. So the reduction we did in the movie was a rightmost derivation in reverse.

Remember that for a non-ambiguous grammar there is only one rightmost derivation and hence there is only one rightmost derivation in reverse.

Remark: You cannot simply scan the string (the roots of the forest) from left to right and choose the first substring that matches the RHS of some production. If you try it in our movie you will reduce T to E right after T appears. The result is not a right sentential form.

| Right Sentential Form | Handle | Reducing Production |

|---|---|---|

| id1 * id2 | id1 | F → id |

| F * id2 | F | T → F |

| T * id2 | id2 | F → id |

| T * F | T * F | T → T * F |

| T | T | E → T |

| E |

The strings that are reduced during the reverse of a rightmost derivation are called the handles. For our example, this is shown in the table on the right.

Note that the string to the right of the handle must contain only terminals. If there was a non-terminal to the right, it would have been reduced in the RIGHTmost derivation that leads to this right sentential form.

Often instead of referring to a derivation A→α as a handle, we call α the handle. I should say a handle because there can be more than one if the grammar is ambiguous. However, we are not emphasizing ambiguous grammars.

So (assuming a non-ambiguous grammar) the rightmost derivation in reverse can be obtained by constantly reducing the handle in the current string.

Given a grammar how do you find the handle (a handle if the grammar

is ambiguous) of a string (which must be a right sentential form or

there is no handle)?

Answer: Construct the (a if ambiguous, but we are not so interested

in ambiguous grammars) rightmost derivation for the string and the

handle is the last production you applied (so if you are doing

rightmost derivations in reverse, the handle is the first production

you would reduce by).

But how do you find the rightmost derivation?

Good question, we still have work to do.

Homework: 1, 2.

We use two data structures for these parsers.

shifted(basically pushed, see below) onto the stack will be terminals, which are subsequently

reducedto nonterminals. The bottom of the stack is marked with $ and initially the stack is empty (i.e., has just $).

| Stack | Input | Action |

|---|---|---|

| $ | id1*id2$ | shift |

| $id1 | *id2$ | reduce F→id |

| $F | *id2$ | reduce T→F |

| $T | *id2$ | shift |

| $T* | id2$ | shift |

| $T*id2 | $ | reduce F→id |

| $T*F | $ | reduce T→T*F |

| $T | $ | reduce E→T |

| $E | $ | accept |

A technical point, which explains the usage of a stack is that a handle is always at the TOS. See the book for a proof; the idea is to look at what rightmost derivations can do (specifically two consecutive productions) and then trace back what the parser will do since it does the reverse operations (reductions) in the reverse order.

We have not yet discussed how to decide whether to shift or reduce when both are possible. We have also not discussed which reduction to choose if multiple reductions are possible. These are crucial question for bottom up (shift-reduce) parsing and will be addressed.

Homework: 3.

There are grammars (non-LR) for which no viable algorithm can

decide whether to shift or reduce when both are possible or which

reduction to perform when several are possible.

However, for most languages, choosing a good lexer yields an LR(k)

language of tokens.

For example, ada uses () for both function calls and array

references.

If the lexer returned id for both array names and procedure names

then a reduce/reduce conflict would occur when the stack was

... id ( id

and the input was

) ...

since the id on TOS should be reduced to parameter if the first id

was a procedure name and to expr if the first id was an array name.

A better lexer (and an assumption, which is true in ada, that the

declaration must precede the use) would return proc-id when it

encounters a lexeme corresponding to a procedure name.

It does this by consulting tables that it builds.

I will have much more to say about SLR (simple LR) than the other LR schemes. The reason is that SLR is simpler to understand, but does capture the essence of shift-reduce, bottom-up parsing. The disadvantage of SLR is that there are LR grammars that are not SLR.

The text's presentation is somewhat controversial.

Most commercial compilers use hand-written top-down parsers of the

recursive-descent (LL not LR) variety.

Since the grammars for these languages are not LL(1), the

straightforward application of the techniques we have seen will not

work.

Instead the parsers actually look ahead further than one token, but

only at those few places where the grammar is in fact not LL(1).

Recall that (hand written) recursive descent compilers have a

procedure for each nonterminal so we can customize as needed

.

These compiler writers claim that they are able to produce much

better error messages than can readily be obtained by going to LR

(with its attendant requirement that a parser-generator be used since

the parsers are too large to construct by hand).

Note that compiler error messages are a very important user interface

issue and that with recursive descent one can augment the procedure

for a nonterminal with statements like

if (nextToken == X) then error(expected Y here

)

Nonetheless, the claims made by the text are correct, namely.

We now come to grips with the big question

:

How does a shift-reduce parser know when to shift and when to

reduce?

This will take a while to answer in a satisfactory manner.

The unsatisfactory answer is that the parser has tables that say in

each situation

whether to shift or reduce (or announce error,

or announce acceptance).

To begin the path toward the answer, we need several definitions.

An item is a production with a marker saying how far the parser has gotten with this production. Formally,

Definition: An (LR(0)) item of a grammar is a production with a dot added somewhere to the RHS.

Note: A production with n symbols on the RHS, generates n+1 items.

Examples:

The item E → E · + T signifies that the parser has just processed input that is derivable from E (i.e., reducible to E) and will look for input derivable from + T.

The item E → E + T · indicates that the parser has just

seen the entire RHS and must consider reducing it to E.

Important: consider reducing

does not mean

reduce

.

The parser groups certain items together into states. As we shall see, the items within a given state are treated similarly.

Our goal is to construct first the canonical LR(0)

collection of states and then a DFA called the LR(0) automaton

(technically not a DFA since it has no dead state

).

To construct the canonical LR(0) collection formally and present the parsing algorithm in detail we shall

Augmenting the grammar is easy. We simply add a new start state S' and one production S'→S. The purpose is to detect success, which occurs when the parser is ready to reduce S to S'.

So our example grammar

E → E + T | T

T → T * F | F

F → ( E ) | id

is augmented by adding the production E' → E.

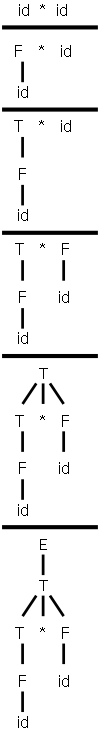

I hope the following interlude will prove helpful. When I was first preparing to present SLR a few years ago, I was struck by how much it looked like we were working with a DFA that came from some (unspecified and unmentioned) NFA. It seemed that by first doing the NFA, I could give some insight, especially since that is how we proceeded last chapter with lexers.

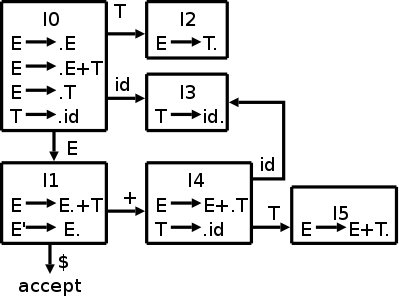

Since our current example would generate an NFA with many states and hence a big diagram, let's consider instead the following extremely simple grammar.

E → E + T

E → T

T → id

When augmented this becomes

E' → E

E → E + T

E → T

T → id

When the dots are added we get 10 items (4 from the second

production, 2 each from the other three).

See the diagram at the right.

We begin at E' → · E since it is the

start item.

Note that there are four

Note that there are four kinds

of edges.

If we are at the item E→E·+T (the dot indicating that we have seen an E and now need a +) and then shift a + from the input to the stack, we move to the item E→E+·T. If the dot is before a non-terminal, the parser needs a reduction with that non-terminal as the LHS.

Now we come to the idea of closure, which I illustrate in the diagram with the ε's. I hope this will help you understand the idea of closure, which like ε in regular expressions, leads to nondeterminism.

Look at the start state. The placement of the dot indicates that we next need to see an E. Since E is a nonterminal, we won't see it in the input, but will instead have to generate it via a production. Thus by looking for an E, we are also looking for any production that has E on the LHS. This is indicated by the two ε's leaving the top left box. Similarly, there are ε's leaving the other three boxes where the dot is immediately to the left of a nonterminal.

Remark: Perhaps instead of saying also looking

for

I should say really looking for

.

As with regular expressions, we combine n-items

connected by

an ε arc into a d-item

.

The actual terminology used is that we combine these items into a

set of items (later referred to as a state).

For example all four items in the left column of the diagram above

are combined into the state or item set labelled I0 in

the diagram on the right.

There is another combination that occurs. The top two n-items in the left column of the diagram above both have E transitions (outgoing arcs labeled E). Since we are considering these two n-items to be the same d-item and the arcs correspond to the same transition, the two targets (the top two n-items in the 2nd column of the diagram above) are combined. A d-item has all the outgoing arcs of the original n-items it contains. This is the way we converted an NFA into a DFA via the subset algorithm described in the previous chapter.

I0, I1, etc are called (LR(0)) item sets. The DFA containing these item sets as states and the state transitions described above is called the LR(0) automaton.

| Stack | Symbols | Input | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| $0 | id+id$ | Shift to 3 | |

| $03 | id | +id$ | Reduce by T→id |

| $02 | T | +id$ | Reduce by E→T. |

| $01 | E | +id$ | Shift to 4 |

| $014 | E+ | id$ | Shift to 3 |

| $0143 | E+id | $ | Reduce by T→id |

| $0145 | E+T | $ | Reduce by E→E+T |

| $01 | E | $ | Accept |

We start in the initial state with the symbols column empty and the input full. The $'s are just end markers. From state 0, called I0 in my diagram (following the book they are called I's since they are sets of items), we can only shift in the id (the nonterminals will appear in the symbols column). This brings us to I3 so we push a 3 onto the stack

In I3 we first notice that there is no outgoing arc labeled with a

terminal; hence we cannot do a shift.

However, we do see a completed production in the box (the dot is on

the extreme right).

Since the RHS consists solely of terminals, having the dot at the

end means that we have seen (i.e., shifted) in the input the entire

RHS of this production and are ready to perform a reduction.

To reduce we pop the stack for each symbol in the RHS since we are

replacing the RHS by the LHS.

This time the RHS has one symbol so we pop the stack once and also

remove one symbol from the symbols column.

The stack corresponds to moves (i.e., state transtions) so we are

undoing the move to 3 and we are temporarily

in 0 again.

But the production has a T on the LHS so we follow the T transition

from 0 to 2, push T onto Symbols, and push 2 on.to the stack.

In I2 we again see no possible shift, but do see a completed production. This time the RHS contains a non-terminal so is not simply the result of shifting in symbols, but also reflects previous reductions. We again perform the indicated reduction, which takes us to I1

You might think that at I1 we could reduce using the completed bottom production, but that is wrong. This item (E'→E·) is special and can only be applied when we are at the end of the input string.

Thus the next two steps are shifts of + and id, sending us to 3

again, where, as before, we have no choice but to reduce the id to T

and are in step 5 ready for the

big one

.

The production in 5 has three symbols on the RHS so we pop (back up) three times again temporarily landing in 0, but the RHS puts us in 1.

Perfect! We have just E as a symbol and the input is empty so we are ready to reduce by E'→E, which signifies acceptance.

Now we rejoin the book and say it more formally.

Actually there is more than mere formality coming. For the example above, we had no choices, but that was because the example was simple. We need more machinery to insure that we never have two or more possible moves to choose among. Specifically, we will need FOLLOW sets, the same ones we calculated for top-down parsing.

Say I is a set of items and one of these items is A→α·Bβ. This item represents the parser having seen α and records that the parser might soon see the remainder of the RHS. For that to happen the parser must first see a string derivable from B. Now consider any production starting with B, say B→γ. If the parser is to make progress on A→α·Bβ, it will need to be making progress on one such B→·γ. Hence we want to add all the latter productions to any state that contains the former. We formalize this into the notion of closure.

For any set of items I, CLOSURE(I) is formed as follows.

Example: Recall our main example

E' → E

E → E + T | T

T → T * F | F

F → ( E ) | id

CLOSURE({E' → · E})

contains 7 elements.

The 6 new elements are the 6 original productions each with a dot

right after the arrow.

Make sure you understand why all 6 original

productions are added.

It is not because the E'→E production is special.

If X is a grammar symbol, then moving from A→α·Xβ to A→αX·β signifies that the parser has just processed (input derivable from) X. The parser was in the former position and (input derivable from) X was on the input; this caused the parser to go to the latter position. We (almost) indicate this by writing GOTO(A→α·Xβ,X) is A→αX·β. I said almost because GOTO is actually defined from item sets to item sets not from items to items.

Definition: If I is an item set and X is a grammar symbol, then GOTO(I,X) is the closure of the set of items A→αX·β where A→α·Xβ is in I.

I really believe this is very clear, but I understand that the formalism makes it seem confusing. Let me begin with the idea.

We augment the grammar and get this one new production; take its closure. That is the first element of the collection; call it I0. Try GOTOing from I0, i.e., for each grammar symbol, consider GOTO(I0,X); each of these (almost) is another element of the collection. Now try GOTOing from each of these new elements of the collection, etc. Start with jane smith, add all her friends F, then add the friends of everyone in F, called FF, then add all the friends of everyone in FF, etc

The (almost)

is because GOTO(I0,X) could be

empty so formally we construct the canonical collection of LR(0)

items, C, as follows

This GOTO gives exactly the arcs in the DFA I constructed earlier. The formal treatment does not include the NFA, but works with the DFA from the beginning.

Definition: The above collection of item sets (so this is a set of sets) is called the canonical LR(0) collection and the DFA having this collection as nodes and the GOTO function as arcs is called the LR(0) automaton.

Homework:

Construct the LR(0) automaton for the

following grammar (which produces simple postfix expressions).

S → S S + | S S * | a

Don't forget to augment the grammar.

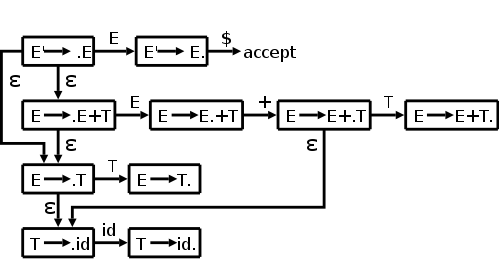

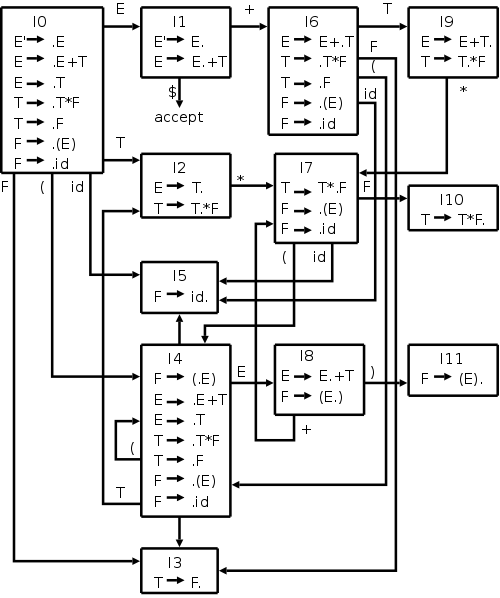

Our main example

E' → E

E → E + T | T

T → T * F | F

F → ( E ) | id

is larger than the toy I did before.

The NFA would have 2+4+2+4+2+4+2=20 states (a production with k

symbols on the RHS gives k+1 N-states since there k+1 places to

place the dot).

This gives rise to 12 D-states.

However, the development in the book, which we are following now,

constructs the DFA directly.

The resulting diagram is on the right.

Start constructing the diagram on the board:

Begin with {E' → ·E},

take the closure, and then keep applying GOTO.