Operating Systems

Start Lecture #9

Remark: Lab 4 is due in two weeks

from today, 9 April 2008.

3.5.8 Cleaning Policy (Paging Daemons)

Done earlier

The only point to add is now that we know replacement algorithms

one can suggest an implementation.

If a clock-like algorithm is used for victim selection, one can have

a two handed clock with one hand (the paging daemon) staying ahead

of the other (the one invoked by the need for a free frame).

The front hand simply writes out any page it hits that is dirty and

thus the trailing hand is likely to see clean pages and hence is

more quickly able to find a suitable victim.

3.5.9 Virtual Memory Interface

Skipped.

3.6 Implementation Issues

3.6.1 Operating System Involvement with Paging

When must the operating system be involved with paging?

- During process creation.

The OS must guess at the size of the process and then allocate a

page table and a region on disk to hold the pages that are not

memory resident.

A few pages of the process must be loaded.

- The Ready→Running transition.

Real memory must be allocated for the page table if the table

has been swapped out (which is permitted when the process is not

running).

Some hardware register(s) must be set to point to the page

table.

There can be many page tables resident, but the hardware must be

told the location of the page table for the running

process—the active

page table.

The MMU must be cleared (unless it contains a process id

field).

- Processing a page fault.

Lots of work is needed; see 3.6.2 just below.

- Process termination.

Free the page table and the disk region for swapped out pages.

3.6.2 Page Fault Handling

What happens when a process, say process A, gets a page fault?

Compare the following with the processing for a trap command and for

an interrupt.

- The hardware detects the fault and traps to the kernel

(switches to supervisor mode and saves state).

- Some assembly language code save more state, establishes the

C-language (or another programming language) environment, and

calls

the OS.

- The OS determines that a page fault occurred and which page

was referenced.

- If the virtual address is invalid, process A is killed.

If the virtual address is valid, the OS must find a free frame.

If there is no free frames, the OS selects a victim frame.

Call the process owning the victim frame, process B.

(If the page replacement algorithm is local, the B=A.)

- The PTE of the victim page is updated to show that the page is

no longer resident.

- If the victim page is dirty, the OS schedules an I/O write to

copy the frame to disk and blocks A waiting for this I/O to

occur.

As we know, this is really not what happens since there

is

always

a free frame thanks to the page cleaning

daemon.

- Assuming process A needed to be blocked (i.e., the victim page

is dirty) the scheduler is invoked to perform a context switch.

- Tanenbaum

forgot

some here.

- The process selected by the scheduler (say process C)

runs.

- Perhaps C is preempted for D or perhaps C blocks and D

runs and then perhaps D is blocked and E runs, etc.

- When the I/O to write the victim frame completes, a disk

interrupt occurs. Assume processes C is running at the

time.

- Hardware trap / assembly code / OS determines I/O done.

- The scheduler marks A as ready.

- The scheduler picks a process to run, maybe A, maybe B,

maybe C, maybe another processes.

- At some point the scheduler does pick process A to run.

Recall that at this point A is still executing OS code.

- Now the O/S has a free frame (this may be much later in wall

clock time if a victim frame had to be written).

The O/S schedules an I/O to read the desired page into this free

frame.

Process A is blocked (perhaps for the second time) and hence the

process scheduler is invoked to perform a context

switch.

- Again, another process is selected by the scheduler as above

and eventually a Disk interrupt occurs when the I/O completes

(trap / asm / OS determines I/O done). The PTE in process A is

updated to indicate that the page is in memory.

- The O/S may need to fix up process A (e.g. reset the program

counter to re-execute the instruction that caused the page

fault).

- Process A is placed on the ready list and eventually is chosen

by the scheduler to run.

Recall that process A is executing O/S code.

- The OS returns to the first assembly language routine.

- The assembly language routine restores registers, etc. and

returns

to user mode.

The user's program running as process A is unaware

that all this happened (except for the time delay).

3.6.3 Instruction Backup

A cute horror story.

The 68000 was so bad in this regard that an early demand paging

system for the 68000, used two processors one running one

instruction behind.

If the first got a page fault, there wasn't always enough

information to figure out what to do so (for example did a register

pre-increment occur), the system switched to the

second processor after bringing in the faulting page.

The next generation machine, the 68010, provided extra information

on the stack so the horrible 2-processor kludge was no longer

necessary.

Don't worry about instruction backup; it is very machine dependent

and modern implementations tend to get it right.

3.6.4 Locking (Pinning) Pages in Memory

We discussed pinning jobs already.

The same (mostly I/O) considerations apply to pages.

3.6.5 Backing Store

The issue is where on disk do we put pages that are not in frames.

- For program text, which is presumably read only, a good choice

is the file executable itself.

- What if we decide to keep the data and stack each contiguous

on the backing store.

Data and stack grow so we must be prepared to grow the space on

disk, which leads to the same issues and problems as we saw with

MVT.

- If those issues/problems are painful, we can scatter the pages

on the disk.

- That is we employ paging!

- This is NOT demand paging.

- Need a table to say where the backing space for each page is

located.

- This corresponds to the page table used to tell where in

real memory a page is located.

- The format of the

memory page table

is determined by

the hardware since the hardware modifies/accesses it. It

is machine dependent.

- The format of the

disk page table

is decided by the OS

designers and is machine independent.

- If the format of the memory page table were flexible,

then we might well keep the disk information in it as

well.

But normally the format is not flexible, and hence this

is not done.

- What if we felt disk space was too expensive and wanted to put

some of these disk pages on say tape?

Ans: We use demand paging of the disk blocks! That way

"unimportant" disk blocks will migrate out to tape and are brought

back in if needed.

Since a tape read requires seconds to complete (because the

request is not likely to be for the sequentially next tape block),

it is crucial that we get very few disk block faults.

Homework: Assume every memory reference takes 0.1

microseconds to execute providing the reference page is memory

resident.

Assume a page fault takes 10 milliseconds to service providing the

necessary disk block is actually on the disk.

Assume a disk block fault takes 10 seconds service.

So the worst case time for a memory reference is 10.0100001

seconds.

Finally assume the program requires that a billion memory references

be executed.

- If the program is always completely resident, how long does it

take to execute?

- If 0.1% of the memory references cause a page fault, but all the disk

blocks are on the disk, how long does the program take to execute

and what percentage of the time is the program waiting for a page

fault to complete?

- If 0.1% of the memory references cause a page fault and 0.1% of the

page faults cause a disk block fault, how long does the program

take to execute and what percentage of the time is the program

waiting for a disk block fault to complete?

3.6.6 Separation of Policy and Mechanism

Skipped.

3.7 Segmentation

Up to now, the virtual address space has been contiguous.

- Among other issues this makes memory management difficult when

there are more that two dynamically growing regions.

- With two regions you start them on opposite sides of the virtual

space as we did before.

- Better is to have many virtual address spaces each starting at

zero.

- This split up is user visible.

So a segment is a logical split up of the address space.

Unlike with (user-invisible) paging, segment boundaries occur at

logical point, e.g., at the end of a procedure.

- Eases flexible protection and sharing:

One places in a single segment a unit that is logically shared.

This would be the natural method to implement shared libraries.

- When shared libraries are implemented on paging systems, the

design essentially mimics segmentation by treating a collection

of pages as a segment.

This is more complicated since one must ensure that the end of

the unit to be shared occurs on a page boundary (this is done by

padding).

- Without segmentation (equivalently said with just one segment) all

procedures are packed together so if one changes in size all the

virtual addresses following are changed and the program must be

re-linked.

With each procedure in a separate segment this

relinking would be limited to the symbols defined or used in the

modified procedure.

Homework:

Explain the difference between internal fragmentation and external

fragmentation.

Which on occurs in paging systems?

Which one occurs in systems using pure segmentation?

** Two Segments

Late PDP-10s and TOPS-10

- One shared text segment, that can also contain shared

(normally read only) data.

- One (private) writable data segment.

- Permission bits on each segment.

- Which kind of segment is better to evict?

- Swapping out the shared segment hurts many tasks.

- The shared segment is read only (probably) so no writeback

is needed.

One segment

is simply swapping, e.g. OS/MVT done

above.

** Three Segments

Traditional (early) Unix shown at right.

- Shared text marked execute only.

- Data segment (global and static variables).

- Stack segment (automatic variables).

- Since the text doesn't grow, this was sometimes treated as 2

segments by combining text and data into one segment.

But then the text could not be shared.

** Four Segments

Just kidding.

** General (Not Necessarily Demand) Segmentation

Segmentation is a user-visible division of a process into

multiple variable-size segments.

It enables fine-grained sharing and protection.

For example, one can share the text segment in early unix.

With segmentation, the virtual address has two components:

the segment number and the offset in the segment.

Segmentation does not mandate how the program is

stored in memory.

- One possibility is that the entire program must be in memory

in order to run it.

Use whole process swapping.

Early versions of Unix did this.

- Can also implement demand segmentation (see below).

- More recently, segmentation is combined with demand paging

(done below).

Any segmentation implementation requires a segment table with one

entry for each segment.

- A segment table is similar to a page table.

- Entries are called STEs, Segment Table Entries.

- Each STE contains the base address of the segment and the

limit value (the size of the segment).

- Why is there no limit value in a page table?

- Answer: All pages are the same size so the limit is obvious.

The address translation for segmentation is

(seg#, offset) --> if (offset<limit) base+offset else error.

3.7.1 Implementation of Pure Segmentation

Pure Segmentation means segmentation without paging.

Segmentation, like whole program swapping, exhibits external

fragmentation (sometimes called checkerboarding.

(See the treatment of OS/MVT for a review of

external fragmentation and whole program swapping).

Since segments are smaller than programs (several segments make up

one program), the external fragmentation is not as bad as with whole

program swapping.

But it is still a problem.

As with whole program swapping, compaction can be employed.

| Consideration | Demand

Paging | Demand

Segmentation |

|---|

|

|

|

| Programmer aware | No | Yes |

| How many addr spaces | 1 | Many |

| VA size > PA size | Yes | Yes |

|

|

|

Protect individual

procedures separately

| No | Yes

|

|

|

|

Accommodate elements

with changing sizes

| No | Yes

|

|

|

|

| Ease user sharing | No | Yes |

|

|

|

| Why invented

| let the VA size

exceed the PA size

| Sharing, Protection,

independent addr spaces

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Internal fragmentation

| Yes | No, in principle

|

| External fragmentation | No | Yes |

| Placement question | No | Yes |

| Replacement question | Yes | Yes |

** Demand Segmentation

Same idea as demand paging, but applied to segments.

- If a segment is loaded, base and limit are stored in the STE and

the valid bit is set in the STE.

- The STE is accessed for each memory reference (not really,

there is probably a TLB).

- If the segment is not loaded, the valid bit is unset.

The base and limit as well as the disk address of the segment is

stored in the an OS table.

- A reference to a non-loaded segment generate a segment fault

(analogous to page fault).

- To load a segment, we must solve both the placement question and the

replacement question (for demand paging, there is no placement question).

- Pure segmentation was once implemented by Burroughs in the B5500.

I believe the implementation was in fact demand segmentation

but I am not sure.

Demand segmentation is not used in modern systems.

The table on the right compares demand paging

with demand segmentation.

The portion above the double line is from Tanenbaum.

** 3.7.2 and 3.7.3 Segmentation With (Demand) Paging

These two sections of the book cover segmentation combined with

demand paging in two different systems.

Section 3.7.2 covers the historic Multics system of the 1960s (it

was coming up at MIT when I was an undergraduate there).

Multics was complicated and revolutionary.

Indeed, Thompson and Richie developed (and named Unix) partially in

rebellion to the complexity of Multics.

Multics is no longer used.

Section 3.7.3 covers the Intel Pentium hardware, which

offers a segmentation+demand-paging scheme that is not used by any

of the current operating systems (OS/2 used it in the past).

The Pentium design permits one to convert

the system into a

pure damand-paging scheme and that is the common usage today.

I will present the material in the following order.

- Describe segmentation+paging (not demand paging) generically,

i.e. not tied to any specific hardware or software.

- Note the possibility of using demand paging (again

generically).

- Give some details of the Multics implementation.

- Give some details of the Pentium hardware, especially how it

can emulate straight demand paging.

** Segmentation With (non-demand) Paging

One can combine segmentation and paging to get advantages of

both at a cost in complexity.

In particular, user-visible, variable size segments are the most

appropriate units for protection and sharing; the addition of

(non-demand) paging eliminates the placement question and external

fragmentation (at the small average cost of 1/2 page internal

fragmentation per segment).

The basic idea is to employ (non-demand) paging on each segment.

A segmentation plus paging scheme has the following properties.

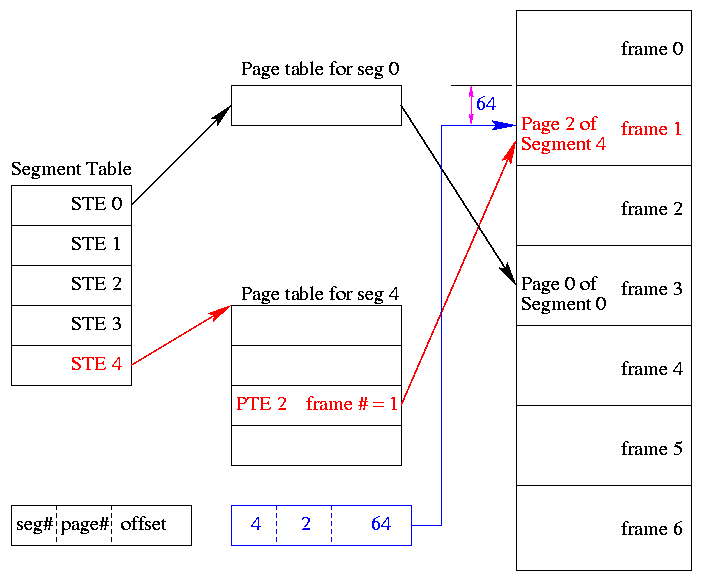

- A virtual address becomes a triple:

(seg#, page#, offset).

- Each segment table entry (STE) points to the page table for

that segment.

Compare this with a

multilevel page table.

- The physical size of each segment is a multiple of the page

size (since the segment consists of pages).

The logical size is not; instead we keep the exact size in the

STE (limit value) and terminate the process if it referenced

beyond the limit.

In this case the last page of each segment is partially wasted

(internal fragmentation).

- The page# field in the address gives the entry in the chosen page

table and the offset gives the offset in the page.

- From the limit field, one can easily compute the size of the

segment in pages (which equals the size of the corresponding page

table in PTEs).

- A straightforward implementation of segmentation with paging

would requires 3 memory references (STE, PTE, referenced word) so a

TLB is crucial.

- Some books carelessly say that segments are of fixed size.

This

is wrong.

They are of variable size with a fixed maximum and with

the requirement that the physical size of a segment is a multiple

of the page size.

- Keep protection and sharing information on segments.

This works well for a number of reasons.

- A segment is variable size.

- Segments and their boundaries are user-visible

- Segments are shared by sharing their page tables.

This eliminates the problem mentioned above with

shared pages.

- Since we have paging, there is no placement question and

no external fragmentation.

- The problems are the complexity and the resulting 3 memory

references for each user memory reference.

The complexity is real.

The three memory references would be fatal were it not for TLBs,

which considerably ameliorate the problem.

TLBs have high hit rates and for a TLB hit there is essentially

no penalty.

Although it is possible to combine segmentation with non-demand

paging, I do not know of any system that did this.

Homework: 36.

Homework: Consider a 32-bit address machine using

paging with 8KB pages and 4 byte PTEs.

How many bits are used for

the offset and what is the size of the largest page table?

Repeat the question for 128KB pages.

So far this question has been asked before.

Repeat both parts assuming the system also has segmentation with at most 128

segments.

** Segmentation With Demand Paging

There is very little to say.

The previous section employed (non-demand) paging on each segment.

For the present scheme, we employ demand paging on each segment,

that is we perform fetch-on-demand for the pages of each segment.

The Multics Scheme

Multics was the first system to employ segmentation plus demand

paging.

The implementation was as described above with just a few wrinkles,

some of which we discuss now together with some of the parameter

values.

- The Multics hardware (GE-645) was word addressable, with

36-bit words (the 645 predates bytes).

- Each virtual address was 34-bits in length and was divided

into three parts as mentioned above.

The seg# field was the high-order 18 bits;

the page# field was the next 6 bits; and

the offset was the low-order 10 bits.

- The actual implementation was more complicated and the full

34-bit virtual address was not present in one place in an

instruction.

- Thus the system supported up to 218=256K segments,

each of size up to 216=64K (36-bit) words.

- Since the segment table can have 256K STEs (called

descriptors), the table itself can be large and is itself

demand-paged.

- Multics permits some segments to be demand-paged while other

segments are not paged; a bit in each STE distinguishes the two

cases.

The Pentium Scheme

The Pentium design implements a trifecta:

Depending on the setting of a various control bits the Pentium

scheme can be pure demand-paging, pure segmentation, or segmentation

with demand-paging.

The Pentium supports 214=16K segments, each of size up

to 232 bytes.

- This would seem to require a 14+32=46 bit virtual address, but

that is not how the Pentium works.

The segment number is not part of the virtual address

found in normal instructions.

- Instead separate instructions are used to specify which are

the currently active

code segment

and data segment

(and other less important segments).

Technically, the CS register is loaded with the selector

of the active code segment and the DS register is loaded with

the selector

of the active data register.

- When the selectors are loaded, the base and limit values are

obtained from the corresponding STEs (called descriptors).

- There are actually two flavors of segments, some are private

to the process; others are system segments (including the OS

itself), which are addressable (but not necessarily accessible)

by all processes.

Once the 32-bit segment base and the segment limit are determined,

the 32-bit address from the instruction itself is compared with the

limit and, if valid, is added to the base and the sum is called the

32-bit linear address

.

Now we have three possibilities depending on whether the system is

running in pure segmentation, pure demand-paging, or segmentation

plus demand-paging mode.

-

In pure segmentation mode the linear address is treated as the

physical address and memory is accessed.

-

In segmentation plus demand-paging mode, the linear address is

broken into three parts since the system implements

2-level-paging.

That is, the high-order 10 bits are used to index into the

1st-level page table (called the page directory).

The directory entry found points to a 2nd-level page table and

the next 10 bits index that table (called the page table).

The PTE referenced points to the frame containing the desired

page and the lowest 12 bits of the linear address (the offset)

finally point to the referenced word.

If either the 2nd-level page table or the desired page are not

resident, a page fault occurs and the page is made resident

using the standard demand paging model.

-

In pure demand-paging mode all the segment bases are zero and

the limits are set to the maximum.

Thus the 32-bit address in the instruction become the linear

address without change (i.e., the segmentation part is

effectively) disabled.

Then the (2-level) demand paging procedure just described is

applied.

Current operating systems for the Pentium use this last mode.

3.8 Research on Memory Management

Skipped

3.9 Summary

Read

Some Last Words on Memory Management

We have studied the following concepts.

- Segmentation / Paging / Demand Loading (fetch-on-demand).

- Each is a yes or no alternative.

- This gives 8 possibilities.

- Placement and Replacement.

- Internal and External Fragmentation.

- Page Size and locality of reference.

- Multiprogramming level and medium term scheduling.

Chapter 4 File Systems

There are three basic requirements for file systems.

- Size: Store very large amounts of data.

- Persistence: Data survives the creating process.

- Concurrent Access: Multiple processes can access the data

concurrently.

High level solution: Store data in files that together form a file

system.

4.1 Files

4.1.1 File Naming

Very important.

A major function of the file system is to supply uniform naming.

Unix-like operating systems extend the name space of files to

encompass devices as well

Does each file have a unique name?

Answer: Often no.

We will discuss this below when we study

links.

File Name Extensions

The extensions are suffixes attached to the file names and are

intended to in some why describe the high-level structure of the

file's contents.

For example, consider the .html

extension

in class-notes.html

, the name of the file we are viewing.

Depending on the system and application, these extensions can have

little or great significance.

The extensions can be

- Conventions just for humans.

For example letter.teq (my convention) signifies to me that this

letter is written the in troff text formatting language and uses

the eqn preprocessor to handle mathematical equations.

Neither linux, troff, nor equ place any significance in the .teq

extension.

- Conventions giving default behavior for some programs.

- The emacs editor by default edits .html files in html

mode.

However, emacs can edit such files in any mode and can edit

any file in html mode.

It just needs to be told to do so during the editing

session.

- The firefox browser assumes that an .html extension

signifies that the file is written in the html markup

language.

However, having <html> ... </html> inside the

file works as well.

- The gzip file compressor/decompressor appends the .gz

extension means that the file is already a compressed file

but accepts a --suffix flag.

- Default behaviors for the operating system or window manager or

desktop environment.

- Click on .xls file in windows and excel is started.

- Click on .xls file in nautilus under linux and open office

is started.

- Required for certain programs.

- The gnu C compiler (and probably other C compilers)

requires C programs be have the .c (or .h) extension, and

requires assembler programs to have the .s extension.

- Required by the operating system

- MS-DOS treats .com files specially.

Case Sensitive?

Should file names be case sensitive.

For example, do x.y, X.Y, x.Y all name the same file?

There is no clear answer.

- Unix-like systems employ case sensitive file names so the three

names given above are distinct.

- Windows systems employ case insensitive file names to the

three names given above are equivalent.

- Mathematicians (and others) often "consider an element x of a

set X" so use case sensitive naming.

- Normal English usage often employs case insensitivity

(e.g. capitalizing a word at the beginning of a sentence does

not change the word)

4.1.2 File Structure

How should the file be structured.

Alternatively, how does the OS interpret the contents of a file.

A file can be interpreted as a

- Byte stream

- Unix, dos, windows.

- Maximum flexibility.

- Minimum structure.

- All structure on a file is imposed by the applications

that use it, not by the system itself.

- (fixed size-) Record stream: Out of date

- 80-character records for card images.

- 133-character records for line printer files.

Column 1 was for control (e.g., new page) Remaining 132

characters were printed.

- Varied and complicated beast.

- Indexed sequential.

- B-trees.

- Supports rapidly finding a record with a specific

key.

- Supports retrieving (varying size) records in key order.

- Treated in depth in database courses.

4.1.3 File Types

The traditional file is simply a collection of data that forms the

unit of sharing for processes, even concurrent processes.

These are called regular files.

The advantages of uniform naming have encouraged the inclusion

in the file system of objects that are not simply collections of

data.

Regular Files

Some regular files contain lines of text and are called (not

surprisingly) text files or ascii files.

Each text line concludes with some end of line indication:

on unix this is a newline (a.k.a line feed) in MS-DOS it is the two

character sequence carriage return

followed by newline.

Ascii, with only 7 bits per character, is poorly suited for

most human languages other than English.

Latin-1 (8 bits) is a little better with support for most Western

European Languages.

Perhaps, with growing support for more varied character sets, ascii

files will be replaced by unicode (16 bits) files.

The Java and Ada programming languages (and perhaps others) already

support unicode.

An advantage of all these formats is that they can be directly

printed on a terminal or printer.

Other regular files, often referred to as binary files, do not

represent a sequence of characters.

For example, a four-byte, twos-complement representation of

integer in the range from roughly -2 billion to +2 billion is

definitely not to be thought of as 4 latin-1 characters, one per

byte.

Just because a file is unstructured (i.e., is a byte stream) from

the OS perspective does not mean that applications cannot impose

structure on the bytes.

So a document written without any explicit formatting in MS word is

not simply a sequence of ascii (or latin-1 or unicode) characters.

On unix, an executable file must begin with a certain

magic number

in the first few bytes.

For a native executable, the remainder of the file has a well

defined format.

Another option is for the magic number to be the ascii

representation of the two characters #!

in which case the

next word

gives the location of the executable program that

is to be run with the current file fed in as input.

That is how interpreted (as opposed to compiled) languages work in

unix.

#!/usr/bin/perl

perl script

Strongly Typed Files

In some systems the type of the file (which is often specified by

the extension) determines what you can do with the file.

This make the easy and (hopefully) common case easier and, more

importantly, safer.

It tends to make the unusual case harder.

For example, you have a program that turns out data (.dat) files.

Now you want to use it to turn out a java file, but the type of the

output is data and cannot be easily converted to type java and hence

cannot be given to the java compiler.