Operating Systems

Start Lecture #7

Remark: Lab 3 (banker) assigned.

It is due in 2 NYU weeks, which is 3 calendar weeks.

** (non-demand) Paging

Simplest scheme to remove the requirement of contiguous physical

memory.

- Chop the program into fixed size pieces called

pages, which are invisible to the user.

Tanenbaum sometimes calls pages

virtual pages.

- Chop the real memory into fixed size pieces called

page frames or

simply frames.

- The size of a page (the page size) = size of a frame (the frame

size).

- Sprinkle the pages into the frames.

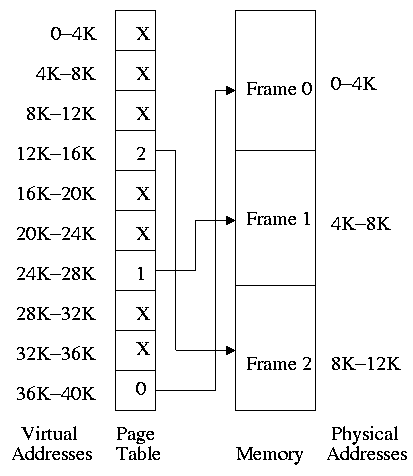

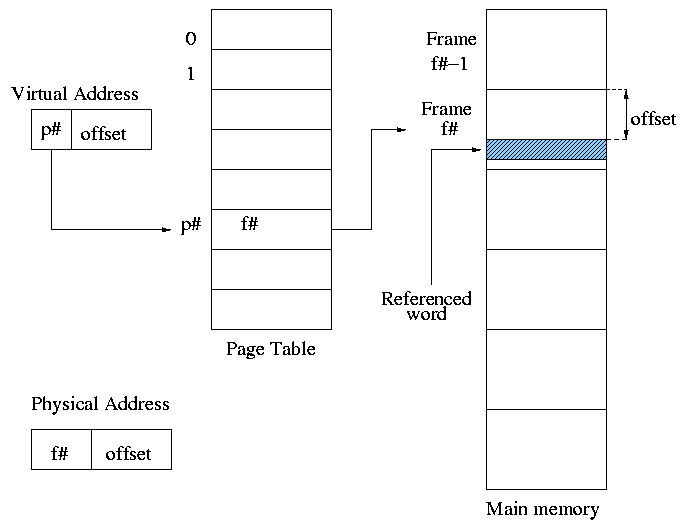

- Keep a table (called the page table) having

an entry for each page.

The page table entry or PTE for page p contains

the number of the frame f that contains page p.

Example: Assume a decimal machine with

page size = frame size = 1000.

Assume PTE 3 contains 459.

Then virtual address 3372 corresponds to physical address 459372.

Properties of (non-demand) paging (without segmentation).

- Entire job must be memory resident to run.

- No holes, i.e. no external fragmentation.

- If there are 50 frames available and the page size is 4KB than a

job requiring ≤ 200KB will fit, even if the available frames are

scattered over memory.

- Hence (non-demand) paging is useful.

- Introduces internal fragmentation approximately equal to 1/2 the

page size for every process (really every segment).

- Can have a job unable to run due to insufficient memory and

have some (but not enough) memory available.

This is not called external fragmentation since it is

not due to memory being fragmented.

- Eliminates the placement question. All pages are equally

good since don't have external fragmentation.

- The replacement question remains.

- Since page boundaries occur at

random

points and can

change from run to run (the page size can change with no effect on

the program--other than performance), pages are not appropriate

units of memory to use for protection and sharing.

But if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

Segmentation, which is discussed later, is more appropriate for

protection and sharing.

- Virtual address space remains contiguous.

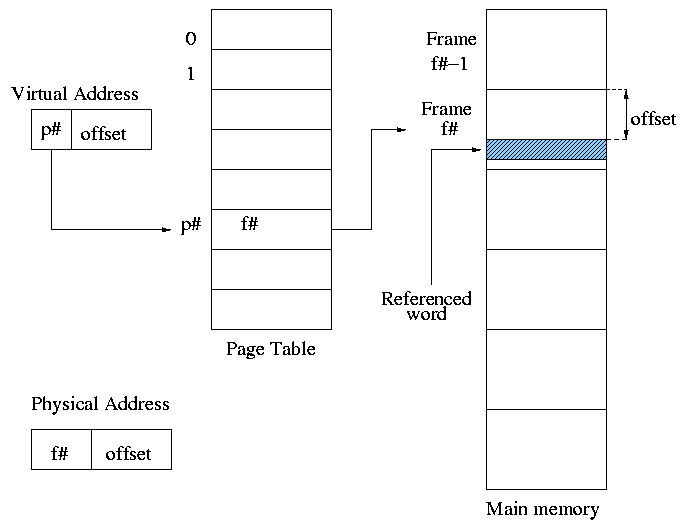

Address translation

- Each memory reference turns into 2 memory references

- Reference the page table

- Reference central memory

- This would be a disaster!

- Hence the MMU caches page#→frame# translations.

This cache is kept near the processor and can be accessed

rapidly.

- This cache is called a translation lookaside buffer (TLB) or

translation buffer (TB).

- For the above example, after referencing virtual address 3372,

there would be an entry in the TLB containing the mapping

3→459.

- Hence a subsequent access to virtual address 3881 would be

translated to physical address 459881 without an extra memory

reference.

Naturally, a memory reference for location 459881 itself would be

required.

Choice of page size is discuss below.

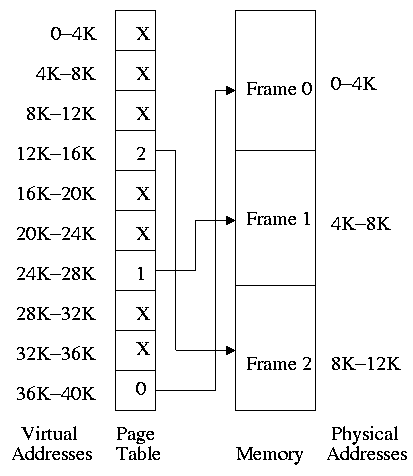

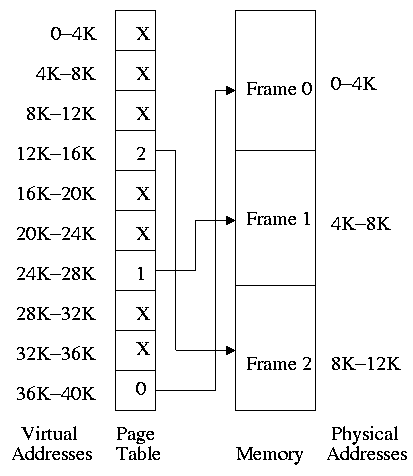

Homework:

Using the page table of Fig. 3.9, give the physical address

corresponding to each of the following virtual addresses.

- 20

- 4100

- 8300

3.3 Virtual Memory (meaning Fetch on Demand)

The idea is to enable a program to execute even if only the active

portion of its address space is memory resident.

That is, we are to swap in and swap out portions of

a program.

In a crude sense this could be called automatic overlays

.

Advantages

- Can run a program larger than the total physical memory.

- Can increase the multiprogramming level since the total size of

the active, i.e. loaded, programs (running + ready + blocked) can

exceed the size of the physical memory.

- Since some portions of a program are rarely if ever used, it

is an inefficient use of memory to have them loaded all the

time. Fetch on demand will not load them if not used and will

(hopefully) unload them during replacement if they are not used

for a long time.

- Simpler for the user than overlays or aliasing variables

(older techniques to run large programs using limited memory).

Disadvantages

- More complicated for the OS.

- Execution time less predictable (depends on other jobs).

- Can over-commit memory.

The Memory Management Unit and Virtual to Physical Address Translation

The memory management unit is a piece of hardware in the processor

that translates virtual addresses (i.e., the addresses in the

program) into physical addresses (i.e., real hardware addresses in

the memory).

The memory management unit is abbreviated as and normally referred

to as the MMU.

(The idea of an MMU and virtual to physical address translation

applies equally well to non-demand paging and in olden days the

meaning of paging and virtual memory included that case as well.

Sadly, in my opinion, modern usage of the term paging and virtual

memory are limited to fetch-on-demand memory systems, typically some

form of demand paging.)

** 3.3.1 Paging (Meaning Demand Paging)

The idea is to fetch pages from disk to memory when they are

referenced, with a hope of getting the most actively used pages in

memory.

The choice of page size is discussed below.

Paging is very common: More complicated variants, multilevel-level

paging and paging plus segmentation (both of which we will

discuss), dominates modern operating systems.

Started by the Atlas system at Manchester University in the 60s

(Fortheringham).

Each PTE continues to contain the frame number if the page is

loaded.

But what if the page is not loaded (exists only on disk)?

- The PTE has a flag indicating if the page is loaded (can think of

the X in the diagram on the right as indicating that this flag is

not set).

- If the page is not loaded, the location on disk could be kept

in the PTE, but normally it is not

(discussed below).

- When a reference is made to a non-loaded page (sometimes

called a non-existent page, but that is a bad name), the system

has a lot of work to do. We give more details

below.

- Choose a free frame, if one exists.

- What if there is no free frame?

Make one!

- Choose a victim frame.

- More later on how to choose a victim.

- This is the replacement question

- Write the victim back to disk if it is dirty,

- Update the victim PTE to show that it is not loaded.

- Now we have a free frame.

- Copy the referenced page from disk to the free frame.

- Update the PTE of the referenced page to show that it is

loaded and give the frame number.

- Do the standard paging address translation

(p#,off)-->(f#,off).

Really not done quite this way

- There is

always

a free frame because ...

- ... there is a deamon active that checks the number of free frames

and if this is too low, chooses victims and

pages them out

(writing them back to disk if dirty).

- Deamon reactivated when low water mark passed and suspended

when high water mark passed.

Homework: 9.

3.3.2 Page tables

A discussion of page tables is also appropriate for (non-demand)

paging, but the issues are more acute with demand paging and the

tables can be much larger. Why?

- The total size of the active processes is no longer limited to

the size of physical memory.

Since the total size of the processes is greater, the total size

of the page tables is greater and hence concerns over the size of

the page table are more acute.

- With demand paging an important question is the choice of a

victim page to page out.

Data in the page table can be useful in this choice.

We must be able access to the page table very quickly since it is

needed for every memory access.

Unfortunate laws of hardware.

- Big and fast are essentially incompatible.

- Big and fast and low cost is hopeless.

So we can't just say, put the page table in fast processor registers,

and let it be huge, and sell the system for $1000.

The simplest solution is to put the page table in main memory.

However it seems to be both too slow and two big.

- This solution seems too slow since all memory references now

require two reference.

- We will soon see how to speed up the references and for many

programs eliminate extra reference by using a

TLB.

- This solution seems too big.

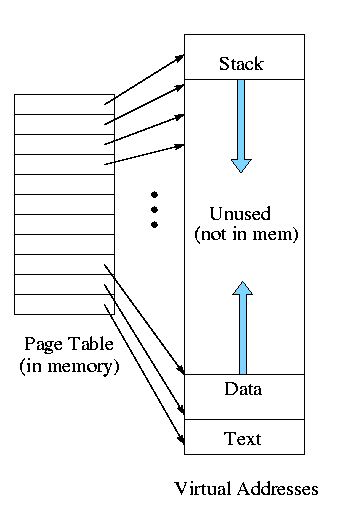

- Currently we are considering contiguous virtual

addresses ranges (i.e. the virtual addresses have no holes).

- One often puts the stack at one end of the virtual address

space and the global (or static) data at the other end and

let them grow towards each other.

- The virtual memory in between is unused.

- That does not sound so bad.

Why should we care about virtual memory?

- This unused virtual memory can be huge (in address range) and

hence the page table (which is stored in real memory)

will mostly contain unneeded PTEs.

- Works fine if the maximum virtual address size is small, which

was once true (e.g., the PDP-11 of the 1970s) but is no longer the

case.

- A

fix

is to use multiple levels of mapping.

We will see two examples below:

multilevel page tables and

segmentation plus paging.

Structure of a Page Table Entry

Each page has a corresponding page table entry (PTE).

The information in a PTE is used by the hardware and its format is

machine dependent; thus the OS routines that access PTEs are not portable.f

Information set by and used by the OS is normally kept in other OS tables.

(Actually some systems, those with software

TLB reload, do not require hardware access to

the page table.)

The page table is index by the page number; thus the page number

is not stored in the table.

The following fields are often present in a PTE.

- The valid bit.

This tells if the page is currently loaded (i.e., is in a

frame).

If set, the frame number is valid.

It is also called the presence or

presence/absence bit.

If a page is accessed with the valid bit unset, a

page fault is generated by the hardware.

- The frame number.

This field is the main reason for the table.

It gives the virtual to physical address translation.

- The Modified bit.

Indicates that some part of the page has been written since it

was loaded.

This is needed if the page is evicted so that the OS can tell if

the page must be written back to disk.

- The referenced bit.

Indicates that some word in the page has been referenced.

Used to select a victim: unreferenced pages make good victims by

the locality property (discussed below).

- Protection bits.

For example one can mark text pages as execute only.

This requires that boundaries between regions with different

protection are on page boundaries.

Normally many consecutive (in logical address) pages have the

same protection so many page protection bits are redundant.

Protection is more naturally done with

segmentation, but in many

current systems, it is done with paging (since the systems don't

utilize segmentation, even though the hardware supports it).

We will soon understand why the disk address of non-resident pages

is not in the PTE: a PTE is loaded into the TLB,

which is used for address translation for resident pages, page

faults trap to the OS.

3.3.3 Speeding Up Paging

As mentioned above the simple scheme of storing the page table in

its entirety in central memory alone appears to be both too slow and

too big.

We address both these issues here, but note that a second solution

to the size question (segmentation) is discussed later.

Translation Lookaside Buffers (and General Associative Memory)

Note: Tanenbaum suggests that associative

memory

and translation lookaside buffer

are

synonyms.

This is wrong.

Associative memory is a general concept of which translation

lookaside buffer is a specific example.

An associative memory is a

content addressable memory.

That is you access the memory by giving the value of some

field (called an index) and the hardware searches all the records

and returns the record whose index field contains the requested value.

For example

Name | Animal | Mood | Color

======+========+==========+======

Moris | Cat | Finicky | Grey

Fido | Dog | Friendly | Black

Izzy | Iguana | Quiet | Brown

Bud | Frog | Smashed | Green

If the index field is Animal and Iguana is given, the associative

memory returns

Izzy | Iguana | Quiet | Brown

A Translation Lookaside Buffer

or TLB is an associate memory where the index field

is the page number.

The other fields include the frame number, dirty bit, valid bit,

etc.

Note that unlike the situation with a the page table, the page

number is stored in the TLB; indeed it is the index

field.

A TLB is small and expensive but at least it

is fast.

When the page number is in the TLB, the frame number is returned

very quickly.

On a miss, a TLB reload is performed.

The page number is looked up in the page table.

The record found is placed in the TLB and a victim is discarded (not

really discarded, dirty and referenced bits are copied back to the

PTE).

There is no placement question since all TLB entries are accessed at

the same time and hence are equally suitable.

But there is a replacement question.

As the size of the TLB has grown, some processors have switched

from single-level, fully-associative, unified TLBs to multi-level,

set-associative, separate instruction and data, TLBs.

We are actually discussing caching, but using different

terminology.

- Page frames are a cache for pages (one could say that

central memory is a cache of the disk).

- The TLB is a cache of the page table.

- Also the processor almost surely has a cache (most likely

several) of central memory.

- In all the cases, we have small-and-fast acting as a cache

of big-and-slow.

However what is big-and-slow in one level of caching, can be

small-and-fast in another level.

Software TLB Management

The words above assume that, on a TLB miss, the MMU (i.e., hardware

and not the OS) loads the TLB with the needed PTE and then performs

the virtual to physical address translation.

This implies that the OS need not be concerned with TLB misses.

Some newer systems do this in software, i.e., the

OS is involved.

Homework: 15.

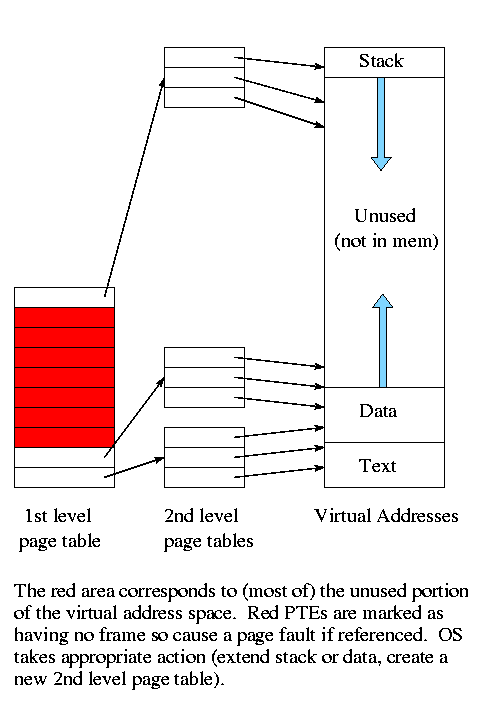

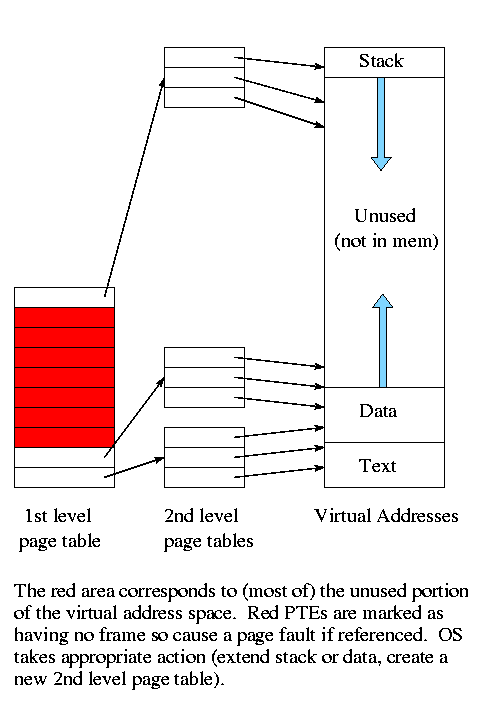

Multilevel page tables

Recall the diagram above showing

the data and stack growing towards each other.

Most of the virtual memory is the unused space between the data and

stack regions.

However, with demand paging this space does not waste real

memory.

But the single large page table does waste real

memory.

The idea of multi-level page tables (a similar idea is used in Unix

i-node-based file systems, which we study later when we do I/O) is

to add a level of indirection and have a page table containing

pointers to page tables.

- Imagine one big page table, which we will (eventually) call

the second level page table.

- We want to apply paging to this large table, viewing it as

simply memory not as a page table.

So we (logically) cut it into pieces each the size of a page.

Note that many (typically 1024 or 2048) PTEs fit in one page so

there are far fewer of these pages than PTEs.

- Now construct a first level page table containing PTEs

that point to the pages produced in the previous bullet.

- This first level PT is small enough to store in memory.

It contains one PTE for every page of PTEs in the 2nd level PT,

which reduces space by a factor of one or two thousand.

- But since we still have the 2nd level PT, we have made the

world bigger not smaller!

- Don't store in memory those 2nd level page tables all of whose

PTEs refer to unused memory.

That is

use demand paging on the (second level) page table!

This idea can be extended to three or more levels.

The largest I know of has four levels.

We will be content with two levels.

Address Translation With a 2-Level Page Table

For a two level page table the virtual address is divided into

three pieces

+-----+-----+-------+

| P#1 | P#2 | Offset|

+-----+-----+-------+

- P#1, page number sub 1, gives the index into the first level

page table.

- Follow the pointer in the corresponding PTE to reach the frame

containing the relevant 2nd level page table.

- P#2 gives the index into this 2nd level page table.

- Follow the pointer in the corresponding PTE to reach the frame

containing the (originally) requested page.

- Offset gives the offset in this frame where the originally

requested word is located.

Do an example on the board

The VAX used a 2-level page table structure, but with some wrinkles

(see Tanenbaum for details).

Naturally, there is no need to stop at 2 levels.

In fact the SPARC has 3 levels and the Motorola 68030 has 4 (and the

number of bits of Virtual Address used for P#1, P#2, P#3, and P#4

can be varied).

Inverted Page Tables

For many systems the virtual address range is much bigger that the

size of physical memory.

In particular, with 64-bit addresses, the range is 264

bytes, which is 16 million terabytes.

If the page size is 4KB and a PTE is 4 bytes, a full page table

would be 16 thousand terabytes.

A two level table would still need 16 terabytes for the first level

table, which is stored in memory.

A three level table reduces this to 16 gigabytes, which is still

large and only a 4-level table gives a reasonable memory footprint

of 16 megabytes.

An alternative is to instead keep a table indexed by frame number.

The content of entry f contains the number of the page currently

loaded in frame f.

This is often called a frame table as well as an

inverted page table.

Now there is one entry per frame.

Again using 4KB pages and 4 byte PTEs, we see that the table would

be a constant 0.1% of the size of real memory.

But on a TLB miss, the system must search the

inverted page table, which would be hopelessly slow except that some

tricks are employed.

Specifically, hashing is used.

Also it is often convenient to have an inverted table as we will

see when we study global page replacement algorithms.

Some systems keep both page and inverted page tables.

3.4 Page Replacement Algorithms (PRAs)

These are solutions to the replacement question.

Good solutions take advantage of locality when choosing the

victim page to replace.

- Temporal locality: If a word is referenced

now, it is likely to be referenced in the near

future.

This argues for caching referenced words, i.e. keeping

the referenced word near the processor for a while.

- Spatial locality: If a word is referenced

now, nearby words are likely to be referenced in the

near future.

This argues for prefetching words around the currently

referenced word.

- Temporal and spacial locality are lumped together into locality: If any

word in a page is referenced, each word in the page is

likely

to be referenced.

So it is good to bring in the entire page on a miss and to keep

the page in memory for a while.

When programs begin there is no history so nothing to base locality

on.

At this point the paging system is said to be undergoing a cold

start

.

Programs exhibit phase changes

in which the set of pages

referenced changes abruptly (similar to a cold start).

At the point of a phase change, many page faults occur because

locality is poor.

Pages belonging to processes that have terminated are of course

perfect choices for victims.

Pages belonging to processes that have been blocked for a long time

are good choices as well.

Random PRA

A lower bound on performance.

Any decent scheme should do better.

3.4.1 The Optimal Page Replacement Algorithm

Replace the page whose next reference will be furthest in

the future.

- Also called Belady's min algorithm.

- Provably optimal.

That is, no algorithm generates fewer page faults.

- Unimplementable: Requires predicting the future.

- Good upper bound on performance.

3.4.2 The not recently used (NRU) PRA

Divide the frames into four classes and make a random selection from

the lowest nonempty class.

- Not referenced, not modified.

- Not referenced, modified.

- Referenced, not modified.

- Referenced, modified.

Assumes that in each PTE there are two extra flags R (sometimes called

U, for used) and M (often called D, for dirty).

Based on the belief that a page in a lower priority class is a

better victim.

- If a page is not referenced, locality suggests that it

probably will not referenced again soon and hence is a good

candidate for eviction.

- If a clean page (i.e., one that is not modified) is chosen to

evict, the OS does not have to write it back to disk and hence

the cost of the eviction is lower than for a dirty page.

- When a page is brought in, the OS resets R and M (i.e. R=M=0).

- On a read, the hardware sets R.

- On a write, the hardware sets R and M.

We again have the prisoner problem: We do a good job of making little

ones out of big ones, but not the reverse.

We need more resets so every k clock ticks, the OS resets all R bits.

Why not reset M as well?

Answer: If a dirty page has a clear M, we will not copy the page

back to disk and thus the only accurate version of the page is lost!

I suppose one could have two M bits one accurate and one reset, but

I don't know of any system (or proposal) that does so.

What if the hardware doesn't set these bits?

Answer: The OS can uses tricks.

When the bits are reset, the PTE is made to indicate that the page

is not resident (which is a lie).

On the ensuing page fault, the OS sets the appropriate bit(s).

We ignore the tricks and assume the hardware does set the bits.

3.4.3 FIFO PRA

Simple but poor since usage of the page is ignored.

Belady's Anomaly: Can have more frames yet generate

more faults.

An example is given later.

The natural implementation is to have a queue of nodes each

pointing to a resident page.

- When a page is loaded, a node referring to the page is appended to

the tail of the queue.

- When a page needs to be evicted, the head node is removed and the

page referenced is chosen as the victim.

3.4.4 Second chance PRA

Similar to the FIFO PRA, but altered so that a page recently

referenced is given a second chance.

- When a page is loaded, a node referring to the page is

appended to the tail of the queue.

The R bit of the page is cleared.

- When a page needs to be evicted, the head node is removed and

the page referenced is the potential victim.

- If the R bit on this page is unset (the page hasn't been

referenced recently), then the page is the

victim.

- If the R bit is set, the page is given a second chance.

Specifically, the R bit is cleared, the node referring to this

page is appended to the rear of the queue (so it appears to have

just been loaded), and the current head node becomes the

potential victim.

- What if all the R bits are set?

- We will move each page from the front to the rear and will

arrive at the initial condition but with all the R bits now

clear.

Hence we will remove the same page as fifo would have removed,

but will have spent more time doing so.

- Might want to periodically clear all the R bits so that a long

ago reference is forgotten (but so is a recent reference).

3.4.5 Clock PRA

Same algorithm as 2nd chance, but a better

implementation for the nodes: Use a circular list with a single

pointer serving as both head and tail.

Let us begin by assuming that the number of pages loaded is

constant.

- So the size of the node list in 2nd chance is constant.

- Use a circular list for the nodes and have a pointer pointing

to the head entry.

Think of the list as the hours on a clock and the pointer as the

hour hand.

(Hence the name

clock

PRA.)

- Since the number of nodes is constant, the operation we need to

support is replace the

oldest

page by a new page.

- Examine the node pointed to by the (hour) hand.

If the R bit of the corresponding page is set, we give the

page a second chance: clear the R bit, move the hour hand (now the page

looks freshly loaded), and examine the next node.

- Eventually we will reach a node whose corresponding R bit is

clear.

The corresponding page is the victim.

- Replace the victim with the new page (may involve 2 I/Os as

always).

- Update the node to refer to this new page.

- Move the hand forward another hour so that the new page is at the

rear.

Thus when the number of loaded pages is constant, the algorithm is

just like 2nd chance except that only the one pointer (the

clock hand

) is updated.

What if the number of pages is not constant?

- We now have to support inserting a node right before the hour

hand (the rear of the queue) and removing the node pointed to by

the hour hand.

- The natural solution is to double link the circular list.

- In this case insertion and deletion are a little slower than

for the primitive 2nd chance (double linked lists have more

pointer updates for insert and delete).

- So the trade-off is that if there are mostly inserts and

deletes and granting 2nd chances is not too common, use the

original 2nd chance implementation.

If there are mostly replacements and you often give nodes a 2nd

chance, use clock.

LIFO PRA

This is terrible!

Why?

Ans: All but the last frame are frozen once loaded so you can

replace only one frame.

This is especially bad after a phase shift in the program as now the

program is references mostly new pages but only one frame is

available to hold them.