Compilers

Start Lecture #14

8.1.4: Register Allocation

Since registers are the fastest memory in the computer, the ideal

solution is to store all values in registers.

However, there are normally not nearly enough registers for this to

be possible.

So we must choose which values are in the registers at any given time.

Actually this problem has two parts.

- Which values should be stored in registers?

- Which register should each selected value be stored in

The reason for the second problem is that often there are register

requirements, e.g., floating-point values in floating-point

registers and certain requirements for even-odd register pairs

(e.g., 0&1 but not 1&2) for multiplication/division.

8.1.5: Evaluation Order

Sometimes better code results if the quads are reordered.

One example occurs with modern processors that can execute multiple

instructions concurrently, providing certain restrictions are met

(the obvious one is that the input operands must already be

evaluated).

8.2: The Target Language

This is a delicate compromise between RISC and CISC.

The goal is to be simple but to permit the study of nontrivial

addressing modes and the corresponding optimizations.

A charging

scheme is instituted to reflect that complex addressing

modes are not free.

8.2.1: A Simple Target Machine Model

We postulate the following (RISC-like) instruction set

-

Load. LD dest, addr

loads the destination dest with the contents of the

address addr.

LD reg1, reg2 is a register copy.

A question is whether dest can be a memory location or whether

it must be a register.

This is part of the RISC/CISC debate.

In CISC parlance, no distinction is made between load and

store, both are examples of the general move instruction that

can have an arbitrary source and an arbitrary destination.

We will normally not use a memory location for the

destination of a load (or the source of a store).

This implies that we are not able to perform a memory to memory

copy in one instruction.

As will be seen below we charge more for accessing memory

location than for a register.

-

Store. ST addr, src

stores the value of the source src (register) into

the address addr.

-

Computation. OP dest, src1, src2

or dest = src1 OP src2

performs the operation OP on the two source operands src1 and

src2.

For a RISC architecture the three operands must be registers.

If the destination is one of the sources, the source is read

first and then overwritten (in one cycle by utilizing a

master-slave flip-flop, when both are registers).

-

Unconditional branch. BR L

transfers control to the (instruction with) label L.

When used with an address rather than a label it means to

goto that address.

Note that we are using the l-value of the address.

This is unlike the situation with a load instruction in which

case the r-value i.e., the contents of the

address, is loaded into the register.

-

Conditional Branch. Bcond r, L

transfers to the label L if register r satisfies the

condition cond.

For example,

BNEG R0, joe

branches to joe if R0 is negative.

Addressing modes

The addressing modes are not simply RISC-like, as they permit

indirection through memory locations.

Again, note that we shall charge extra for some such operands.

Recall the difference between an l-value and an r-value, e.g. the

difference between the uses of x in

x = y + 3

and

z = x + 12x

The first refer to an address, the second to a value

(stored in that address).

We assume the machine supports the following addressing modes.

-

Variable name.

This is shorthand (or assembler-speak) for the memory location

containing x, i.e., we use the l-value of the variable name.

So

LD R1, a

sets the contents of R1 equal to the contents of a, i.e.,

contents(R1) := contents(a)

Do not get confused here.

The l-value of a is used as the address (that is what the

addressing mode tells us).

But the load instruction itself loads the first operand with

the contents of the second.

That is why it is the r-value of the second operand that is

placed into the first operand.

-

Indexed address.

The address a(reg), where a is a variable name and reg is a

register (i.e., a register number), specifies the address that

is the r-value-of-reg bytes past the address specified by a.

That is, the address is computed as the l-value of a plus the

r-value of reg.

So

LD r1, a(r2)

sets

contents(r1) := contents(a+contents(r2))

NOT

contents(r1) := contents(contents(a)+contents(r2))

Permitting this addressing mode outside a load or store

instruction would strongly suggest a CISC architecture.

-

Indexed constant.

An integer constant can be indexed by a register.

So

LD r1, 8(r4)

sets

contents(r1) := contents(8+contents(r4)).

-

Indirect addressing.

If I is an integer constant and r is a register

(number), the previous addressing mode tells us that I(r)

refers to the address I+contents(r).

The new addressing mode *I(r) refers to the address

contents(I+contents(r)).

The address *r is shorthand for *0(r).

The address *10 is shorthand for

*10(fakeRegisterContainingZero).

So

LD r1, *r2

sets (get ready)

contents(r1) := contents(contents(contents(r2)))

and

LD r1, *50(r2)

sets

contents(r1) := contents(contents(50+contents(r2))).

and

LD r1, *10

sets

contents(r1) := contents(contents(10))

-

Immediate constant.

If a constant is preceded by a # it is treated as an r-value

instead of as a register number.

So

ADD r2, r2, #1

is an increment instruction.

Indeed

ADD 2, 2, #1

does the same thing, but we probably won't write that; for

clarity we will normally write registers beginning with an

r

Addressing Mode Usage

Remember that in 3-address instructions, the variables written are

addresses, i.e., they represent l-values.

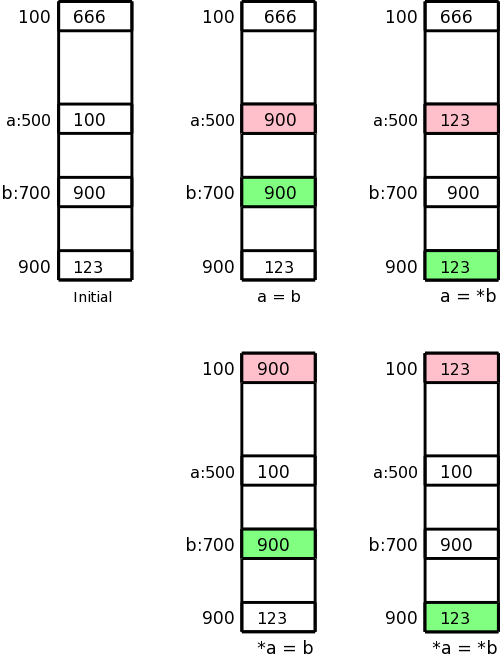

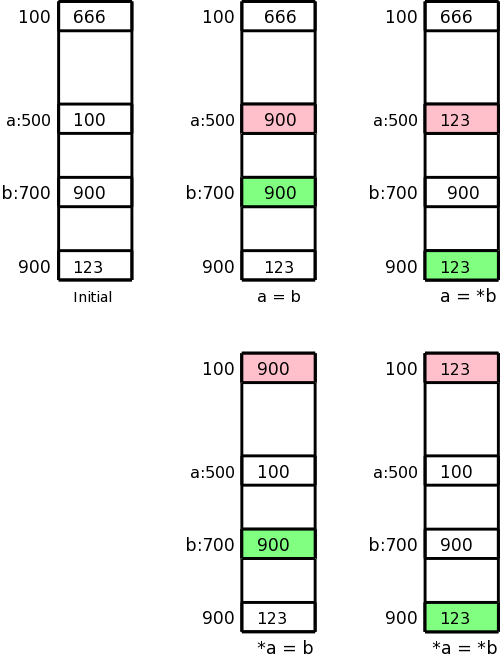

Let us assume the l-value of a is 500 and the l-value b is 700,

i.e., a and b refer to locations 500 and 700 respectively.

Assume further that location 100 contains 666, location 500 contains

100, location 700 contains 900, and location 900 contains 123.

This initial state is shown in the upper left picture.

In the four other pictures the contents of the pink location has

been changed to the contents of the light green location.

These correspond to the three-address assignment statements shown

below each picture.

The machine instructions indicated below implement each of these

assignment statements.

a = b

LD R1, b

ST a, R1

a = *b

LD R1, b

LD R1, 0(R1)

ST a, R1

*a = b

LD R1, b

LD R2, a

ST 0(R2), R1

*a = *b

LD R1, b

LD R1, 0(R1)

LD R2, a

ST 0(R2), R1

Naive Translation of Quads to Instructions

For many quads the naive (RISC-like) translation is 4 instructions.

- Load the first source into a register.

- Load the second source into another register.

- Do the operation.

- Store the result.

Array assignment statements are also four instructions.

We can't have a quad A[i]=B[j] because that needs four addresses and

quads have only three.

Similarly, we can't use an array in a computation statement like

a[i]=x+y because it again would need four addresses.

The instruction x=A[i] becomes (assuming each element of A is 4

bytes; our intermediate code generator already does the

multiplication so we would not generate a multiply here).

LD R0, i

MUL R0, R0, #4

LD R0, A(R0)

ST x, R0

Similarly A[i]=x becomes (again our intermediate code generator

already does the multiplication).

LD R0, x

LD R1, i

MUL R1, R1, #4

ST A(R1), R0

The (C-like) pointer reference x = *p becomes

LD R0, p

LD R0, 0(R0)

ST x, R0

The assignment through a pointer *p = x becomes

LD R0, x

LD R1, p

ST 0(R1), R0

Finally, if x < y goto L becomes

LD R0, x

LD R1, y

SUB R0, R0, R1

BNEG R0, L

Conclusion

With not much additional effort much of the output of lab 4 could

be turned into naive assembly language.

We will not do this.

Instead, we will spend the little time remaining learning how to

generate less-naive assembly language.

8.2.2: Program and Instruction Costs

Generating good code requires that we have a metric, i.e., a way of

quantifying the cost of executing the code.

The run-time cost of a program depends on (among other factors)

- The cost of the generated instructions.

- The number of times the instructions are executed.

Here we just determine the first cost, and use quite a simple metric.

We charge for each instruction one plus the cost of each addressing

mode used.

Addressing modes using just registers have zero cost, while those

involving memory addresses or constants are charged one.

This corresponds to the size of the instruction since a memory

address or a constant is assumed to be stored in a word right after

the instruction word itself.

You might think that we are measuring the memory (or space) cost of

the program not the time cost, but this is mistaken:

The primary space cost is the size of the data, not the size of the

instructions.

One might say we are charging for the pressure on the I-cache.

For example, LD R0, *50(R2) costs 2, the additional cost is for the

constant 50.

I believe that the book special cases the addresses 0(reg) and

*0(reg) so that the 0 is not explicitly stored and not charged for.

The significance for us is calculating the length an instruction such

as

LD R1, 0(R2)

We care about the length of an instruction when we need to generate

a branch that skips over it.

Homework: 1, 2c, 3, 4.

Calculate the cost for 2c.

8.3: Address in the Target Code

There are 4 possibilities for addresses that must be generated

depending on which of the following areas the address refers to.

- The text or code area.

The location of items in this area is statically determined,

i.e., is known at compile time.

- The static area holding global constants.

The location of items in this area is statically determined.

-

The stack holding activation records.

The location of items in this area is not known at compile time.

-

The heap.

The location of items in this area is not known at compile time.

8.3.1: Static Allocation

Returning to the glory days of Fortran, we first consider a system

with only static allocation.

Remember, that with static allocation we know before execution where

all the data will be stored.

There are no recursive procedures; indeed, there is no run-time

stack of activation records.

Instead the ARs (one per procedure) are statically

allocated by the compiler.

Caller Calling Callee

In this simplified situation, calling a parameterless procedure just

uses static addresses and can be implemented by two instructions.

Specifically,

call procA

can be implemented by

ST callee.staticArea, #here+20

BR callee.codeArea

Assume, for convenience, that the return address is the

first location in the activation record (in general, for a

parameterless procedure, the return address would be a

fixed offset from the beginning of the AR).

We use the attribute staticArea for the address of the AR for the

given procedure (remember again that there is no stack and no heap).

What is the mysterious #here+20?

The # we know signifies an immediate constant.

We use here to represent the address of the current

instruction (the compiler knows this value since we are assuming

that the entire program, i.e., all procedures, are compiled at

once).

The two instructions listed contain 3 constants, which means that

the entire sequence takes 5 words or 20 bytes.

Thus here+20 is the address of the instruction after the BR, which

is indeed the return address.

Callee Returning

With static allocation, the compiler knows the address of the

the AR for the callee and we are assuming that the return address is

the first entry.

Then a procedure return is simply

BR *callee.staticArea

Let's make sure we understand the indirect addressing here.

The value callee.staticArea is the address of a memory location

into which the caller placed the return address.

So the branch is not to callee.staticArea, but instead to the

return address, which is the value contained in

callee.staticArea.

Example

We consider a main program calling a procedure P and then

halting.

Other actions by Main and P are indicated by subscripted uses

of other

.

// Quadruples of Main

other1

call P

other2

halt

// Quadruples of P

other3

return

Let us arbitrarily assume that the code for Main starts in location

1000 and the code for P starts in location 2000 (there might be

other procedures in between).

Also assume that each otheri requires 100 bytes (all

addresses are in bytes).

Finally, we assume that the ARs for Main and P begin at 3000 and

4000 respectively.

Then the following machine code results.

// Code for Main

1000: Other1

1100: ST 4000, #1120 // P.staticArea, #here+20

1112: BR 2000 // Two constants in previous instruction take 8 bytes

1120: other2

1220: HALT

...

// Code for P

2000: other3

2100: BR *4000

...

// AR for Main

3000: // Return address stored here (not used

)

3004: // Local data for Main starts here

...

// AR for P

4000: // Return address stored here

4004: // Local data for P starts here

8.3.2: Stack Allocation

We now need to access the ARs from the stack.

The key distinction is that the location of the current AR

is not known at compile time.

Instead a pointer to the stack must be maintained dynamically.

We dedicate a register, call it SP, for this purpose.

In this chapter we let SP point to the bottom of the current AR,

that is the entire AR is above the SP.

Since we are not supporting varargs, there is no advantage to having

SP point to the middle

of the AR as in the previous chapter.

The main procedure (or the run-time library code called before

any user-written procedure) must initialize SP with

LD SP, #stackStart

where stackStart is a known-at-compile-time constant.

The caller increments SP (which now points to the beginning of its

AR) to point to the beginning of the callee's AR.

This requires an increment by the size of

the caller's AR, which of course the caller knows.

Is this size a compile-time constant?

The book treats it as a constant.

The only part that is not known at compile time is the size of the

dynamic arrays.

Strictly speaking this is not part of the AR, but it must be skipped

over since the callee's AR starts after the caller's dynamic arrays.

Perhaps for simplicity we are assuming that there are no dynamic

arrays being stored on the stack.

If there are arrays, their size must be included in some way.

Caller Calling Callee

The code generated for a parameterless call is

ADD SP, SP, #caller.ARSize

ST 0(SP), #here+16 // save return address (book wrong)

BR callee.codeArea

Callee Returning

The return requires code from both the Caller and Callee.

The callee transfers control back to the caller with

BR *0(SP)

Upon return the caller restore the stack pointer with

SUB SP, SP, caller.ARSize

Example

We again consider a main program calling a procedure P and then

halting.

Other actions by Main and P are indicated by subscripted uses of

`other'.

// Quadruples of Main

other1

call P

other2

halt

// Quadruples of P

other3

return

Recall our assumptions that the code for Main starts in location

1000, the code for P starts in location 2000, and each

otheri requires 100 bytes.

Let us assume the stack begins at 9000 (and grows to larger

addresses) and that the AR for Main is of size 400 (we don't need

P.ARSize since P doesn't call any procedures).

Then the following machine code results.

// Code for Main

1000; LD SP, 9000 // Probably done prior to Main

1008: Other1

1108: ADD SP, SP, #400

1116: ST 0(SP), #1132 // Understand the address

1124: BR, 2000

1132: SUB SP, SP, #400

1140: other2

1240: HALT

...

// Code for P

2000: other3

2100: BR *0(SP) // Understand the *

...

// AR for Main

9000: // Return address stored here (not used)

9004: // Local data for Main starts here

9396: // Last word of the AR is bytes 9396-9399

...

// AR for P

9400: // Return address stored here

9404: // Local data for P starts here

Homework: 1, 2d, 3c.

8.3.3: Run-Time Addresses for Names

Basically skipped.

A technical fine point about static allocation and a

corresponding point about the display.

8.4: Basic Blocks and Flow Graphs

As we have seen, for many quads it is quite easy to generate a

series of machine instructions to achieve the same effect.

As we have also seen, the resulting code can be quite inefficient.

For one thing the last instruction generated for a quad is often a

store of a value that is then loaded right back in the next quad (or

one or two quads later).

Another problem is that we don't make much use of the registers.

That is, translating a single quad needs just one or two registers so

we might as well throw out all the other registers on the machine.

Both of the problems are due to the same cause:

Our horizon is too limited.

We must consider more than one quad at a time.

But wild flow of control can make it unclear which quads

are dynamically

near each other.

So we want to consider, at one time, a group of quads for which

the dynamic order of execution is tightly controlled.

We then also need to understand how execution proceeds from one

group to another.

Specifically the groups are called basic blocks and the

execution order among them is captured by the flow graph.

Definition:

A basic block is a maximal collection of consecutive quads

such that

- Control enters the block only at the first instruction.

- Branches (or halts) occur only at the last instruction.

Definition:

A flow graph has the basic blocks as vertices and has edges

from one block to each possible dynamic successor.

We process all the quads in a basic block together

making

use of the fact that the block is not entered or left in

the middle

.

8.4.1: Basic Blocks

Constructing the basic blocks is easy.

Once you find the start of a block, you keep going until you hit a

label or jump.

But, as usual, to say it correctly takes more words.

Definition:

A basic block leader (i.e., first instruction) is any of the

following (except for the instruction just past the entire program).

- The first instruction of the program.

- A target of a (conditional or unconditional) jump.

- The instruction immediately following a jump.

Given the leaders, a basic block starts with a leader and proceeds

up to but not including the next leader.

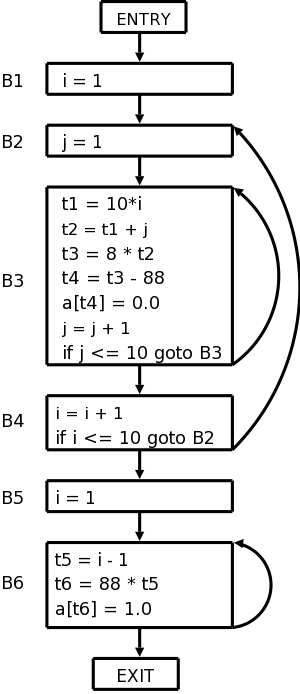

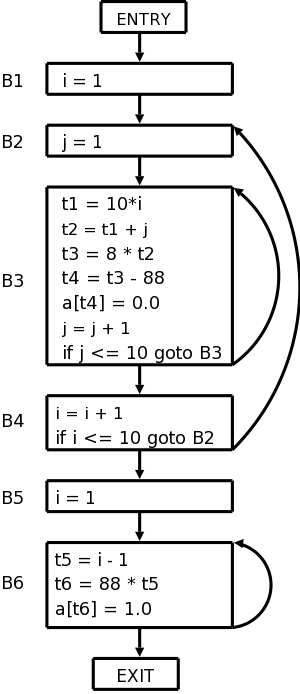

Example

The following code produces a 10x10 real identity matrix

for i from 1 to 10 do

for j from 1 to 10 do

a[i,j] = 0

end

end

for i from 1 to 10 do

a[i,i] = 1.0

end

The following quads do the same thing.

Don't worry too much about how the quads were generated.

1) i = 1

2) j = 1

3) t1 = 10 * i

4) t2 = t1 + j // element [i,j]

5) t3 = 8 * t2 // offset for a[i,j] (8 byte reals)

6) t4 = t3 - 88 // program array starts at [1,1] assembler at [0,0]

7) a[t4] = 0.0

8) j = j + 1

9) if j <= 10 goto (3)

10) i = i + 1

11) if i <= 10 goto (2)

12) i = 1

13) t5 = i - 1

14) t6 = 88 * t5

15) a[t6] = 1.0

16) i = i + 1

17) if i <= 10 goto (13)

Which quads are leaders?

1 is a leader by definition.

The jumps are 9, 11, and 17.

So 10 and 12 are leaders as are the targets 3, 2, and 13.

The leaders are then 1, 2, 3, 10, 12, and 13.

The basic blocks are therefore {1}, {2}, {3,4,5,6,7,8,9}, {10,11},

{12}, and {13,14,15,16,17}.

Here is the code written again with the basic blocks indicated.

1) i = 1

2) j = 1

3) t1 = 10 * i

4) t2 = t1 + j // element [i,j]

5) t3 = 8 * t2 // offset for a[i,j] (8 byte numbers)

6) t4 = t3 - 88 // we start at [1,1] not [0,0]

7) a[t4] = 0.0

8) j = j + 1

9) if J <= 10 goto (3)

10) i = i + 1

11) if i <= 10 goto (2)

12) i = 1

13) t5 = i - 1

14) t6 = 88 * t5

15) a[t6] = 1.0

16) i = i + 1

17) if i <= 10 goto (13)

We can see that once you execute the leader you are assured of

executing the rest of the block in order.

8.4.2: Next Use Information

We want to record the flow of information from instructions that

compute a value to those that use the value.

One advantage we will achieve is that if we find a value has no

subsequent uses, then it is dead and the register holding that value

can be used for another value.

Assume that a quad p assigns a value to x (some would call this

a def of x).

Definition:

A quad q uses the value computed at p (uses

the def) and x is live at q

if q has x as an operand and there is a possible execution path from

p to q that does not pass any other def of x.

Since the flow of control is trivial inside a basic block, we are

able to compute the live/dead status and next use information at the

block leader by a simple backwards scan of the quads (algorithm

below).

Note that if x is dead (i.e., defined before used) on entrance to B

the register containing x can be reused in B.

Computing Live/Dead and Next Use Information

Our goal is to determine whether a block uses a value and if so in

which statement.

The following algorithm for computing uses is quite simple.

Initialize all variables in B as being live

Examine the quads of the block in reverse order.

Assume the quad q computes x and reads y and z

Mark x as dead; mark y and z as live and used at q

When the loop finishes those values that are read before being

written are marked as live and their first use is noted.

The locations x that are written before being read are marked dead

meaning that the value of x on entrance is not used.

8.4.3: Flow Graphs

The nodes of the flow graph are the basic blocks and there is an

edge from P (predecessor) to S (successor) if S might follow P

More formally, such an edge is added if the last statement of P

- is a jump to S (it must be to the leader of S) or

- is not an unconditional jump and S immediately follows P.

Two nodes are added: entry

and exit

.

An edge is added from entry to the first basic block, i.e. the block

that has the first statement of the program as leader.

Edges to the exit are added from any block that could be the last

block executed.

Specifically, edges are added to exit from

- the last block if it doesn't end in an unconditional jump.

- any block that ends in a jump to outside the program.

The flow graph for our example is shown on the right.

8.4.4: Representing Flow Graphs

Note that jump targets are no longer quads but blocks.

The reason is that various optimizations within blocks will change

the instructions and we would have to change the jump to reflect

this.

8.4.5: Loops

For most programs the bulk of the execution time is within loops so

we want to identify these.

Definition:

A collection of basic blocks forms a

loop L

with

loop entry E if

- No block in L other than E has a predecessor outside L.

- All blocks in L have a path to E completely inside L.

The flow graph on the right has three loops.

- {B3}, i.e., B3 by itself.

- {B6}.

- {B2, B3, B4}

Homework: 1.

Remark:

Nothing beyond here will be on the final.

A Word or Two About Global Flow Analysis (unofficial)

We are not covering global flow analysis; it is a key component of

optimization and would be a natural topic in a follow-on course.

Nonetheless there is something we can say just by examining the flow

graphs we have constructed.

For this discussion I am ignoring tricky and important

issues concerning arrays and pointer references (specifically,

disambiguation).

You may wish to assume that the program contains no arrays or

pointers for these comments.

We have seen that a simple backwards scan of the statements in a

basic block enables us to determine the variables that are

live-on-entry and those that are dead-on-entry.

Those variables that do not occur in the block are in neither

category; perhaps we should call them ignored by the block

.

We shall see below that it would be lovely to know which variables

are live/dead-on-exit.

This means which variables hold values at the end of the block that

will / will not be used.

To determine the status of v on exit of a block B, we need to trace

all possible execution paths beginning at the end of B.

If all these paths reach a block where v is dead-on-entry before

they reach a block where v is live-on-entry, then v is dead on exit

for block B.

8.5: Optimization of Basic Blocks

8.5.1: The DAG Representation of Basic Blocks

The goal is to obtain a visual picture of how information flows

through the block.

The leaves will show the values entering the block and as we

proceed up the DAG we encounter uses of these values, defs

(and redefs) of values, and uses of the new values.

Formally, this is defined as follows.

- Create a leaf for the initial value of each variable appearing

in the block.

(We do not know what that the value is, not even if the variable

has ever been given a value).

- Create a node N for each statement s in the block.

- Label N with the operator of s.

This label is drawn inside the node.

- Attach to N those variables for which N is the last def in

the block.

These additional labels are drawn along side of N.

- Draw edges from N to each statement that is the last def of

an operand used by N.

- Designate as output nodes those N whose values are

live on exit

, an officially-mysterious term meaning values

possibly used in another block.

(Determining the live on exit values requires global, i.e.,

inter-block, flow analysis.)

As we shall see in the next few sections various basic-block

optimizations are facilitated by using the DAG.

8.5.2: Finding Local Common Subexpressions

As we create nodes for each statement, proceeding in the static

order of the statements, we might notice that a new node is just

like one already in the DAG in which case we don't need a new node

and can use the old node to compute the new value in addition to the

one it already was computing.

Specifically, we do not construct a new node if an existing node

has the same children in the same order and is labeled with the same

operation.

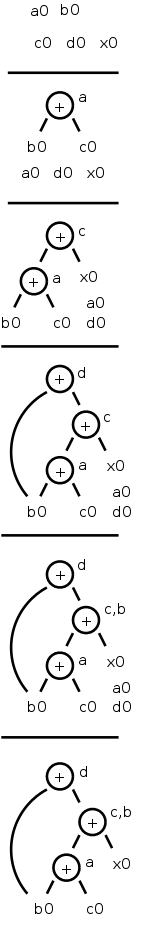

Consider computing the DAG for the following block of code.

a = b + c

c = a + x

d = b + c

b = a + x

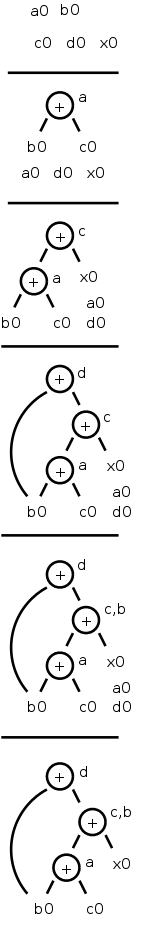

The DAG construction proceeds as follows (the movie on the right

accompanies the explanation).

- First we construct leaves with the initial values.

- Next we process a = b + c.

This produces a node labeled + with a attached and having

b0 and c0 as children.

- Next we process c = a + x.

- Next we process d = b + c.

Although we have already computed b + c in the first statement,

the c's are not the same, so we produce a new node.

- Then we process b = a + x.

Since we have already computed a + x in statement 2, we do not

produce a new node, but instead attach b to the old node.

- Finally, we tidy up and erase the unused initial values.

You might think that with only three computation nodes in the DAG,

the block could be reduced to three statements (dropping the

computation of b).

However, this is wrong.

Only if b is dead on exit can we omit the computation of b.

We can, however, replace the last statement with the simpler

b = c.

Sometimes a combination of techniques finds improvements that no

single technique would find.

For example if a-b is computed, then both a and b are incremented by

one, and then a-b is computed again, it will not be recognized as a

common subexpression even though the value has not changed.

However, when combined with various algebraic transformations, the

common value can be recognized.

8.5.3: Dead Code Elimination

Assume we are told (by global flow analysis) that certain values

are dead on exit.

We examine each root (node with no ancestor) and delete any for

which all attached variables are dead on exit.

This process is repeated since new roots may have appeared.

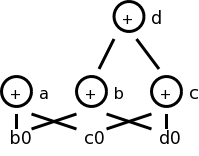

For example, if we are told, for the picture on the right, that c

and d are dead on exit, then the root d can be removed since d is

dead.

Then the rightmost node becomes a root, which also can be removed

(since c is dead).

8.5.4: The Use of Algebraic Identities

Some of these are quite clear.

We can of course replace x+0 or 0+x by simply x.

Similar considerations apply to 1*x, x*1, x-0, and x/1.

Another class of simplifications is strength reduction,

where we replace one operation by a cheaper one.

A simple example is replacing 2*x by x+x on architectures where

addition is cheaper than multiplication.

A more sophisticated strength reduction is applied by compilers that

recognize induction variables

(loop indices).

Inside a

for i from 1 to N

loop, the expression 4*i can be strength reduced to j=j+4 and 2^i

can be strength reduced to j=2*j (with suitable initializations of j

just before the loop).

Other uses of algebraic identities are possible; many require a

careful reading of the language reference manual to ensure their

legality.

For example, even though it might be advantageous to convert

((a + b) * f(x)) * a

to

((a + b) * a) * f(x)

it is illegal in Fortran since the programmer's use of parentheses

to specify the order of operations can not be violated.

Does

a = b + c

x = y + c + b + r

contain a common subexpression of b+c that need be evaluated only

once?

The answer depends on whether the language permits the use of the

associative and commutative law for addition.

(Note that the associative law is invalid for floating point numbers.)

8.5.5: Representation of Array References

Arrays are tricky.

Question: Does

x = a[i]

a[j] = 3

z = a[i]

contain a common subexpression of a[i] that need be evaluated only

once?

The answer depends on whether i=j.

Without some form of disambiguation, we can not be assured that the

values of i and j are distinct.

Thus we must support the worst case condition that i=j and hence the

two evaluations of a[i] must each be performed.

A statement of the form x = a[i] generates a node labeled with the

operator =[] and the variable x, and having children a0,

the initial value of a, and the value of i.

A statement of the form a[j] = y generates a node labeled with

operator []= and three children a0. j, and y, but with no

variable as label.

The new feature is that this node kills all existing nodes depending

on a0.

A killed node can not received any future labels so cannot becomew a

common subexpression.

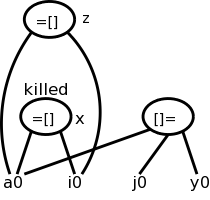

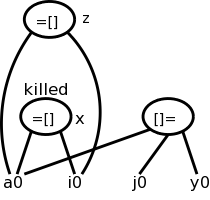

Returning to our example

x = a[i]

a[j] = 3

z = a[i]

We obtain the top figure to the right.

Sometimes it is not children but grandchildren (or other

descendant) that are arrays.

For example we might have

b = a + 8 // b[i] is 8 bytes past a[i]

x = b[i]

b[j] = y

Again we need to have the third statement kill the second node even

though it is caused by a grandchild.

This is shown in the bottom figure.

8.5.6: Pointer Assignment and Procedure Calls

Pointers are even trickier than arrays.

Together they have spawned a mini-industry in disambiguation

,

i.e., when can we tell whether two array or pointer references refer

to the same or different locations.

A trivial case of disambiguation occurs with.

p = &x

*p = y

In this case we know precisely the value of p so the second

statement kills only nodes with x attached.

With no disambiguation information, we must assume

that a pointer can refer to any location.

Consider

x = *p

*q = y

We must treat the first statement as a use of every variable;

pictorially the =* operator takes all current nodes with identifiers

as arguments.

This impacts dead code elimination.

We must treat the second statement as writing every variable.

That is all existing nodes are killed, which impacts common

subexpression elimination.

In our basic-block level approach, a procedure call has properties

similar to a pointer reference:

For all x in the scope of P, we must

treat a call of P as using all nodes with x attached and also

kills those same nodes.

8.5.7: Reassembling Basic Blocks From DAGs

Now that we have improved the DAG for a basic block, we need to

regenerate the quads.

That is, we need to obtain the sequence of quads corresponding to

the new DAG.

We need to construct a quad for every node that has a variable

attached.

If there are several variables attached we chose a live-on-exit

variable, assuming we have done the necessary global flow analysis

to determine such variables).

If there are several live-on-exit variables we need to compute one

and make a copy so that we have both.

An optimization pass may eliminate the copy if it is able to assure

that one such variable may be used whenever the other is

referenced.

Example

Recall the example from our movie

a = b + c

c = a + x

d = b + c

b = a + x

If b is dead on exit, the first three instructions suffice.

If not we produce instead

a = b + c

c = a + x

d = b + c

b = c

which is still an improvement as the copy instruction is less

expensive than the addition on most architectures.

If global analysis shows that, whenever this definition of b is

used, c contains the same value, we can eliminate the copy and use c

in place of b.

Order of Generated Instructions

Note that of the following 5 rules, 2 are due to arrays, and 2 due

to pointers.

- The DAG order must be respected (defs before uses).

- Assignment to an array must follow all assignments to or uses

of the same array that preceded it in the original block (no

reordering of array assignments).

- Uses of an array must follow all (preceding according to the

original block) assignments to it; so the only transformation

possible is reordering uses.

- All variable references must follow all (preceding ...)

procedure calls or assignment through a pointer.

- A procedure call or assignment through a pointer must follow all

(preceding ...) variable references.

Homework: 9.14,

9.15 (just simplify the 3-address code of 9.14 using the two cases

given in 9.15), and

9.17 (just construct the DAG for the given basic block in the two

cases given).

8.6: A Simple Code Generator

A big issue is proper use of the registers, which are often in

short supply, and which are used/required for several purposes.

- Some operands must be in registers.

- Holding temporaries thereby avoiding expensive memory ops.

- Holding inter-basic-block values (loop index).

- Storage management (e.g., stack pointer).

For this section we assume a RISC architecture.

Specifically, we assume only loads and stores touch memory;

that is, the instruction set consists of

LD reg, mem

ST mem, reg

OP reg, reg, reg

where there is one OP for each operation type used in the three

address code.

A major simplification is we assume that, for each three address

operation, there is precisely one machine instruction that

accomplishes the task.

This eliminates the question of instruction selection.

We do, however, consider register usage.

Although we have not done global flow analysis (part of

optimization), we will point out places where live-on-exit

information would help us make better use of the available registers.

Recall that the mem operand in the load LD and store ST

instructions can use any of the previously discussed addressing

modes.

8.6.1: Register and Address Descriptors

These are the primary data structures used by the code generator.

They keep track of what values are in each register as well as where

a given value resides.

- Each register has a register descriptor containing the

list of variables currently stored in this register.

At the start of the basic block all register descriptors are empty.

- Each variable has a address descriptor containing the

list of locations where this variable is currently stored.

Possibilities are its memory location and one or more registers.

The memory location might be in the static area, the stack, or

presumably the heap (but not mentioned in the text).

The register descriptor could be omitted since you can compute it

from the address descriptors.

8.6.2: The Code-Generation Algorithm

There are basically three parts to (this simple algorithm for) code

generation.

- Choosing registers

- Generating instructions

- Managing descriptors

We will isolate register allocation in a function

getReg(Instruction), which is presented later.

First presented is the algorithm to generate instructions.

This algorithm uses getReg() and the descriptors.

Then we learn how to manage the descriptors and finally we study

getReg() itself.

Machine Instructions for Operations

Given a quad OP x, y, z (i.e., x = y OP z), proceed as follows.

Call getReg(OP x, y, z) to get Rx, Ry, and

Rz, the registers to be used for x, y, and z

respectively.

Note that getReg merely selects the registers, it

does not guarantee that the desired values are present

in these registers.

Check the register descriptor for Ry.

If y is not present in Ry, check the address descriptor

for y and issue

LD Ry, y

The book uses y' (not y) as source of the load, where y'

is some location containing y.

I don't see why just y isn't enough.

Perhaps y might also be in a register, but then I don't see why

Ry wouldn't be that register.

- Similar treatment for Rz.

- Generate the instruction

OP Rx, Ry, Rz

Machine Instructions for Copy Statements

When processing

x = y

steps 1 and 2 are the same as above

(getReg() will set Rx=Ry).

Step 3 is vacuous and step 4 is omitted.

This says that if y was already in a register before the copy

instruction, no code is generated at this point.

Since the value of y is not in its memory location,

we may need to store this value back into y at block exit.

Ending the Basic Block

You probably noticed that we have not yet generated any store

instructions; They occur here (and during spill code in getReg()).

We need to ensure that all variables needed by (dynamically)

subsequent blocks (i.e., those live-on-exit) have their current

values in their memory locations.

- Temporaries are never live beyond a basic block so can be

ignored.

- Variables dead on exit (thank you global flow for determining

such variables) are also ignored.

All live on exit variables (for us all non-temporaries) need

to be in their memory location on exit from the block.

Check the address descriptor for each live on exit variable.

If its own memory location is not listed, generate

ST x, R

where R is a register listed in the address descriptor

Managing Register and Address Descriptors

This is fairly clear.

We just have to think through what happens when we do a load, a

store, an OP, or a copy.

For R a register, let Desc(R) be its register descriptor.

For x a program variable, let Desc(x) be its address descriptor.

- Load: LD R, x

- Desc(R) = x (removing everything else from Desc(R))

- Add R to Desc(x) (leaving alone everything else in Desc(x))

- Remove R from Desc(w) for all w ≠ x

(not in 2e please check)

- Store: ST x, R

- Add the memory location of x to Desc(x)

- Operation: OP Rx, Ry, Rz

implementing the quad OP x, y, z

- Desc(Rx) = x

- Desc(x) = Rx

- Remove Rx from Desc(w) for all w ≠ x

- Copy: For x = y after processing the load (if needed)

- Add x to Desc(Ry) (note y not x)

- Desc(x) = R

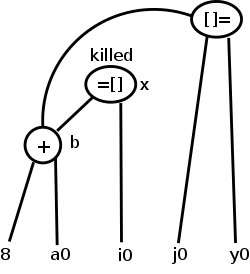

Example

Since we haven't specified getReg() yet, we will assume there are

an unlimited number of registers so we do not need to generate any

spill code (saving the register's value in memory).

One of getReg()'s jobs is to generate spill code when a register needs

to be used for another purpose and the current value is not

presently in memory.

Despite having ample registers and thus not generating spill code,

we will not be wasteful of registers.

- When a register holds a temporary value and there are no

subsequent uses of this value, we reuse that register.

- When a register holds the value of a program variable and

there are no subsequent uses of this value, we reuse that

register providing this value is also in the

memory location for the variable.

- When a register holds the value of a program variable and all

subsequent uses of this value are preceded by a redefinition, we

could reuse this register.

But to know about all subsequent uses may require

live/dead-on-exit knowledge.

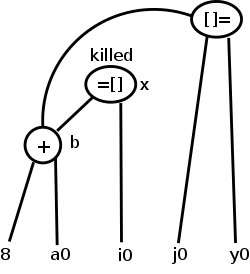

This example is from the book.

I give another example after presenting getReg(), that I believe

justifies my claim that the book is missing an action, as indicated

above.

Assume a, b, c, and d are program variables and t, u, v are

compiler generated temporaries (I would call these t$1, t$2, and

t$3).

The intermediate language program is on the left with the generated

code for each quad shown.

To the right is shown the contents of all the descriptors.

The code generation is explained below the diagram.

t = a - b

LD R1, a

LD R2, b

SUB R2, R1, R2

u = a - c

LD r3, c

SUB R1, R1, R3

v = t + u

ADD R3, R2, R1

a = d

LD R2, d

d = v + u

ADD R1, R3, R1

exit

ST a, R2

ST d, R1

What follows describes the choices made.

Confirm that the values in the descriptors matches the explanations.

- For the first quad, we need all three instructions since nothing

is register resident on block entry.

Since b is not used again, we can reuse its register.

(Note that the current value of b is in its memory location.)

- We do not load a again since its value is R1, which we can reuse

for u since a is not used below.

- We again reuse a register for the result; this time because c is

not used again.

- The copy instruction required a load since d was not in a

register.

As the descriptor shows, a was assigned to the same register, but

no machine instruction was required.

- The last instruction uses values already in registers.

We can reuse R1 since u is a temporary.

- At block exit, lacking global flow analysis, we must assume all

program variables are live and hence must store back to memory any

values located only in registers.

8.6.3: Design of the Function getReg

Consider

x = y OP z

Picking registers for y and z are the same; we just do y.

Choosing a register for x is a little different.

A copy instruction

x = y

is easier.

Choosing Ry

Similar to demand paging, where the goal is to produce an available

frame, our objective here is to produce an available register we can

use for Ry.

We apply the following steps in order until one succeeds.

(Step 2 is a special case of step 3.)

- If Desc(y) contains a register, use of these for Ry.

- If Desc(R) is empty for some registers, pick one of these.

- Pick a register for which the cleaning procedure

generates a minimal number of store instructions.

To clean an in-use register R do the following for each v in Desc(R).

- If Desc(v) includes something besides R, no store is needed

for v.

- If v is x and x is not z, no store is needed since x is

being overwritten.

- No store is needed if there is no further use of v prior to

a redefinition.

This is easy to check for further uses within the block.

If v is live on exit (e.g., we have no global flow analysis),

we need a redefinition later in this block.

- Otherwise a spill ST v, R is generated.

Choosing Rz and Rx, and Processing x = y

As stated above choosing Rz is the same as choosing

Ry.

Choosing Rx has the following differences.

- Since Rx will be written it is not enough for

Desc(x) to contain a register R as in 1. above;

instead, Desc(R) must contain only x.

- If there is no further use of y prior to a redefinition (as

described above for v) and if Ry contains only y (or

will do so after it is loaded), then Ry can be used

for Rx.

Similarly, Rz might be usable for Rx.

getReg(x=y) chooses Ry as above and chooses

Rx=Ry.

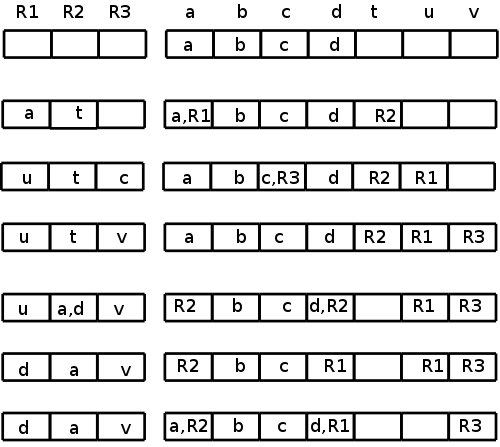

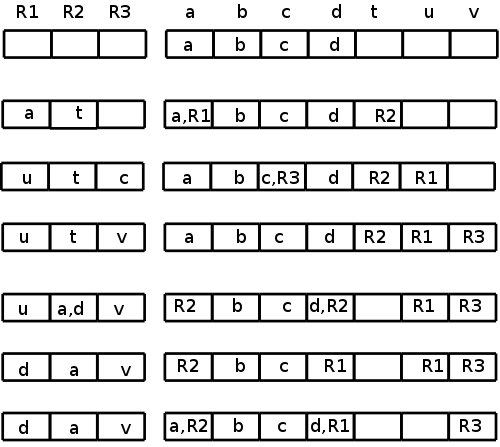

Example

R1 R2 R3 a b c d e

a b c d e

a = b + c

LD R1, b

LD R2, c

ADD R3, R1, R2

R1 R2 R3 a b c d e

b c a R3 b,R1 c,R2 d e

d = a + e

LD R1, e

ADD R2, R3, R1

R1 R2 R3 a b c d e

2e → e d a R3 b,R1 c R2 e,R1

me → e d a R3 b c R2 e,R1

We needed registers for d and e; none were free.

getReg() first chose R2 for d since R2's current contents, the value

of c, was also located in memory.

getReg() then chose R1 for e for the same reason.

Using the 2e algorithm, b might appear to be in R1

(depends if you look in the address or register descriptors).

a = e + d

ADD R3, R1, R2

Descriptors unchanged

e = a + b

ADD R1, R3, R1 ← possible wrong answer from 2e

R1 R2 R3 a b c d e

e d a R3 b,R1 c R2 R1

LD R1, b

ADD R1, R3, R1

R1 R2 R3 a b c d e

e d a R3 b c R2 R1

The 2e might think R1 has b (address descriptor) and also

conclude R1 has only e (register descriptor) so might generate the

erroneous code shown.

Really b is not in a register so must be loaded.

R3 has the value of a so was already chosen for a.

R2 or R1 could be chosen.

If R2 was chosen, we would need to spill d (we must assume live-on-exit,

since we have no global flow analysis).

We choose R1 since no spill is needed: the value of e (the current

occupant of R1) is also in its memory location.

exit

ST a, R3

ST d, R2

ST e, R1

8.7: Peephole Optimization

Skipped.

8.8: Register Allocation and Assignment

Skipped.

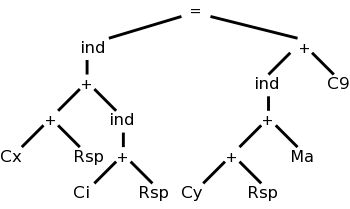

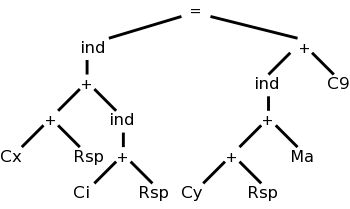

8.9: Instruction Selection by Tree Rewriting (unofficial)

What if a given quad needs several OPs and we have choices?

We would like to be able to describe the machine OPs in a way that

enables us to find a sequence of OPs (and LDs and STs) to do the job.

The idea is that you express the quad as a tree and express each OP

as a (sub-)tree simplification, i.e. the op replaces a subtree by a

simpler subtree.

In fact the simpler subtree is just a single node.

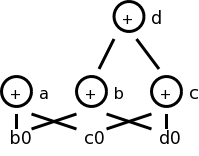

The diagram on the right represents x[i] = y[a] + 9,

where x and y are on the stack and a is in the static area.

M's are values in memory; C's are constants; and R's are registers.

The weird ind (presumably short for indirect) treats its argument as

a memory location.

Compare this to grammars:

A production replaces the RHS by the LHS.

We consider context free grammars where the LHS is a single

nonterminal.

For example, a LD replaces a Memory node with a Register node.

Another example is that

ADD Ri, Ri, Rj

replaces a subtree consisting of a + with both children registers (i

and j) with a Register node (i).

As you do the pattern matching and reductions (apply the

productions), you emit the corresponding code (semantic actions).

So to support a new processor, you need to supply the tree

transformations corresponding to every instruction in the

instruction set.

8.10: Optimal Code Generation for Expressions (unofficial)

This is quite cute.

We assume all operators are binary and label the instruction tree

with something like the height.

This gives the minimum number of registers needed so that no spill

code is required.

A few details follow.

8.10.1: Ershov Numbers

- Draw the

expression tree

, the syntax tree for an expression.

- Label the leaves with 1.

- Label interior nodes with L:

- If the children have the same label x, L=x+1.

This looks like height.

- If the children have different labels, x and y, L=max(x,y).

8.10.2: Generating Code From Labeled Expression Trees

- Recursive algorithm starting at the root.

Each node puts its answer in the highest number register it is

assigned.

The idea is that a node uses (mostly) the same registers as its

sibling.

- If the labels on the children are equal to L, the parent's

label is L+1.

- Give one child L regs ending in highest assigned to

parent.

Note that the lowest reg assigned to the parent is not

used by this child.

The answer appears in top reg assigned to the child, which

is the top reg assigned to the parent.

- Give other child L regs, ending one below the top reg

assigned to the parent.

This child does use the bottom reg assigned to the parent.

The answer appears in top reg assigned to the child, i.e.,

the penultimate parent reg.

- Parent uses a two address OP to compute its answer in the

same reg used by first child, which is the top reg

assigned to the parent.

- If the labels on the children are M<L, the parent is

labeled L.

- Give

bigger

child all L parent regs.

- Give other child M regs ending one below bigger child.

- Parent uses 2-addr OP computing answer in L

- If at a leaf (operand), load it into assigned reg.

Can see this is optimal (assuming you have enough registers).

- Loads each operand only once.

- Performs each operation only once.

- Does no stores.

- Minimal number of registers having the above three properties.

- Show need L registers to produce a result with label L.

- Must compute one side and not use the register containing

its answer before finishing the other side.

- Apply this argument recursively.

8.10.3: Evaluating Expressions with an Insufficient Supply of Registers

Rough idea is to apply the above recursive algorithm, but at each

recursive step, if the number of regs is not enough, store the

result of the first child computed before starting the second.

8.11: Dynamic Programming Code-Generation

Skipped