Operating Systems

================ Start Lecture #6 ================

3.4.2: Detecting Deadlocks with Multiple Unit Resources

This is more difficult.

-

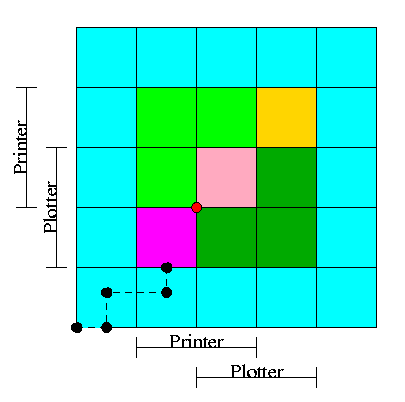

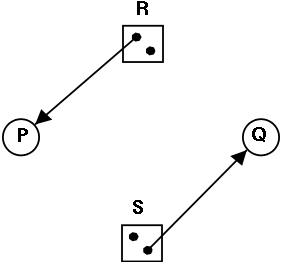

The figure on the right shows a resource allocation graph with

multiple unit resources.

-

Each unit is represented by a dot in the box.

-

Request edges are drawn to the box since they represent a request

for any dot in the box.

-

Allocation edges are drawn from the dot to represent that this

unit of the resource has been assigned (but all units of a resource

are equivalent and the choice of which one to assign is arbitrary).

-

Note that there is a directed cycle in red, but there is no

deadlock. Indeed the middle process might finish, erasing the green

arc and permitting the blue dot to satisfy the rightmost process.

-

The book gives an algorithm for detecting deadlocks in this more

general setting. The idea is as follows.

- look for a process that might be able to terminate (i.e., all

its request arcs can be satisfied).

- If one is found pretend that it does terminate (erase all its

arcs), and repeat step 1.

- If any processes remain, they are deadlocked.

-

We will soon do in detail an algorithm (the Banker's algorithm) that

has some of this flavor.

-

The algorithm just given makes the most optimistic assumption

about a running process: it will return all its resources and

terminate normally.

If we still find processes that remain blocked, they are

deadlocked.

-

In the bankers algorithm we make the most pessimistic

assumption about a running process: it immediately asks for all

the resources it can (details later on “can”).

If, even with such demanding processes, the resource manager can

assure that all process terminates, then we can assure that

deadlock is avoided.

3.4.3: Recovery from deadlock

Preemption

Perhaps you can temporarily preempt a resource from a process. Not

likely.

Rollback

Database (and other) systems take periodic checkpoints. If the

system does take checkpoints, one can roll back to a checkpoint

whenever a deadlock is detected. Somehow must guarantee forward

progress.

Kill processes

Can always be done but might be painful. For example some

processes have had effects that can't be simply undone. Print, launch

a missile, etc.

Remark:

We are doing 3.6 before 3.5 since 3.6 is easier.

3.6: Deadlock Prevention

Attack one of the coffman/havender conditions

3.6.1: Attacking Mutual Exclusion

Idea is to use spooling instead of mutual exclusion. Not

possible for many kinds of resources

3.6.2: Attacking Hold and Wait

Require each processes to request all resources at the beginning

of the run. This is often called One Shot.

3.6.3: Attacking No Preempt

Normally not possible.

That is, some resources are inherently preemptable (e.g., memory).

For those deadlock is not an issue.

Other resources are non-preemptable, such as a robot arm.

It is normally not possible to find a way to preempt one of these

latter resources.

3.6.4: Attacking Circular Wait

Establish a fixed ordering of the resources and require that they

be requested in this order. So if a process holds resources #34 and

#54, it can request only resources #55 and higher.

It is easy to see that a cycle is no longer possible.

Homework: 7.

3.5: Deadlock Avoidance

Let's see if we can tiptoe through the tulips and avoid deadlock

states even though our system does permit all four of the necessary

conditions for deadlock.

An optimistic resource manager is one that grants every

request as soon as it can. To avoid deadlocks with all four

conditions present, the manager must be smart not optimistic.

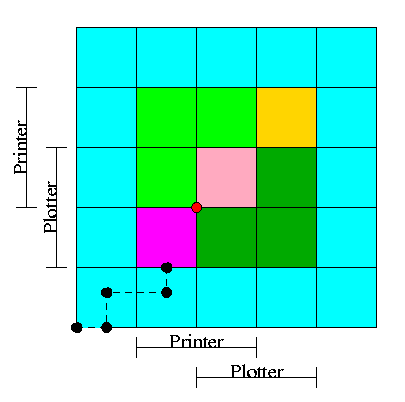

3.5.1 Resource Trajectories

We plot progress of each process along an axis.

In the example we show, there are two processes, hence two axes, i.e.,

planar.

This procedure assumes that we know the entire request and release

pattern of the processes in advance so it is not a practical

solution.

I present it as it is some motivation for the practical solution that

follows, the Banker's Algorithm.

-

We have two processes H (horizontal) and V.

-

The origin represents them both starting.

-

Their combined state is a point on the graph.

-

The parts where the printer and plotter are needed by each process

are indicated.

-

The dark green is where both processes have the plotter and hence

execution cannot reach this point.

-

Light green represents both having the printer; also impossible.

-

Pink is both having both printer and plotter; impossible.

-

Gold is possible (H has plotter, V has printer), but the system

can't get there.

-

The upper right corner is the goal; both processes have finished.

-

The red dot is ... (cymbals) deadlock. We don't want to go there.

-

The cyan is safe. From anywhere in the cyan we have horizontal

and vertical moves to the finish point (the upper right corner)

without hitting any impossible area.

-

The magenta interior is very interesting. It is

- Possible: each processor has a different resource

- Not deadlocked: each processor can move within the magenta

- Deadly: deadlock is unavoidable. You will hit a magenta-green

boundary and then will no choice but to turn and go to the red dot.

-

The cyan-magenta border is the danger zone.

-

The dashed line represents a possible execution pattern.

-

With a uniprocessor no diagonals are possible. We either move to

the right meaning H is executing or move up indicating V is executing.

-

The trajectory shown represents.

- H excuting a little.

- V excuting a little.

- H executes; requests the printer; gets it; executes some more.

- V executes; requests the plotter.

-

The crisis is at hand!

-

If the resource manager gives V the plotter, the magenta has been

entered and all is lost. “Abandon all hope ye who enter

here” --Dante.

-

The right thing to do is to deny the request, let H execute moving

horizontally under the magenta and dark green. At the end of the dark

green, no danger remains, both processes will complete successfully.

Victory!

-

This procedure is not practical for a general purpose OS since it

requires knowing the programs in advance. That is, the resource

manager, knows in advance what requests each process will make and in

what order.

Homework: 10, 11, 12.

3.5.2: Safe States

Avoiding deadlocks given some extra knowledge.

-

Not surprisingly, the resource manager knows how many units of each

resource it had to begin with.

-

Also it knows how many units of each resource it has given to

each process.

-

It would be great to see all the programs in advance and thus know

all future requests, but that is asking for too much.

-

Instead, when each process starts, it announces its maximum usage.

That is each process, before making any resource requests, tells

the resource manager the maximum number of units of each resource

the process can possible need.

This is called the claim of the process.

-

If the claim is greater than the total number of units in the

system the resource manager kills the process when receiving

the claim (or returns an error code so that the process can

make a new claim).

-

If during the run the process asks for more than its claim,

the process is aborted (or an error code is returned and no

resources are allocated).

-

If a process claims more than it needs, the result is that the

resource manager will be more conservative than need be and there

will be more waiting.

Definition: A state is safe

if there is an ordering of the processes such that: if the

processes are run in this order, they will all terminate (assuming

none exceeds its claim).

Recall the comparison made above between detecting deadlocks (with

multi-unit resources) and the banker's algorithm (which stays in

safe states).

- The deadlock detection algorithm given makes the most

optimistic assumption

about a running process: it will return all its resources and

terminate normally.

If we still find processes that remain blocked, they are

deadlocked.

- The banker's algorithm makes the most pessimistic

assumption about a running process: it immediately asks for all

the resources it can (details later on

“can”).

If, even with such demanding processes, the resource manager can

assure that all process terminates, then we can assure that

deadlock is avoided.

In the definition of a safe state no assumption is made about the

running processes; that is, for a state to be safe termination must

occur no matter what the processes do (providing the all terminate

and to not exceed their claims).

Making no assumption is the same as making the most pessimistic

assumption.

Give an example of each of the four possibilities. A state that is

- Safe and deadlocked--not possible.

- Safe and not deadlocked--trivial (e.g., no arcs).

- Not safe and deadlocked--easy (any deadlocked state).

- Not safe and not deadlocked--interesting.

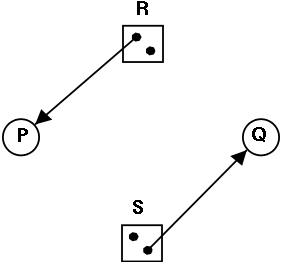

Is the figure on the right safe or not?

Is the figure on the right safe or not?

- You can NOT tell until I give you the initial claims of the

process.

- Please do not make the unfortunately common exam mistake to

give an example involving safe states without giving the

claims.

- For the figure on the right, if the initial claims are:

P: 1 unit of R and 2 units of S (written (1,2))

Q: 2 units of R and 1 units of S (written (2,1))

the state is NOT safe.

- But if the initial claims are instead:

P: 2 units of R and 1 units of S (written (2,1))

Q: 1 unit of R and 2 units of S (written (1,2))

the state IS safe.

- Explain why this is so.

A manager can determine if a state is safe.

-

Since the manager know all the claims, it can determine the maximum

amount of additional resources each process can request.

-

The manager knows how many units of each resource it has left.

The manager then follows the following procedure, which is part of

Banker's Algorithms discovered by Dijkstra, to

determine if the state is safe.

-

If there are no processes remaining, the state is

safe.

-

Seek a process P whose max additional requests is less than

what remains (for each resource type).

-

If no such process can be found, then the state is

not safe.

-

The banker (manager) knows that if it refuses all requests

excepts those from P, then it will be able to satisfy all

of P's requests. Why?

Ans: Look at how P was chosen.

-

The banker now pretends that P has terminated (since the banker

knows that it can guarantee this will happen). Hence the banker

pretends that all of P's currently held resources are returned. This

makes the banker richer and hence perhaps a process that was not

eligible to be chosen as P previously, can now be chosen.

-

Repeat these steps.

Example 1

A safe state with 22 units of one resource

| process | initial claim | current alloc | max add'l |

|---|

| X | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Y | 11 | 5 | 6 |

| Z | 19 | 10 | 9 |

| Total | 16 |

| Available | 6 |

-

One resource type R with 22 unit

-

Three processes X, Y, and Z with initial claims 3, 11, and 19

respectively.

-

Currently the processes have 1, 5, and 10 units respectively.

-

Hence the manager currently has 6 units left.

-

Also note that the max additional needs for the processes are 2,

6, 9 respectively.

-

So the manager cannot assure (with its current

remaining supply of 6 units) that Z can terminate. But that is

not the question.

-

This state is safe

-

Use 2 units to satisfy X; now the manager has 7 units.

-

Use 6 units to satisfy Y; now the manager has 12 units.

-

Use 9 units to satisfy Z; done!

Example 2

An unsafe state with 22 units of one resource

| process | initial claim | current alloc | max add'l |

|---|

| X | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Y | 11 | 5 | 6 |

| Z | 19 | 12 | 7 |

| Total | 18 |

| Available | 4 |

Start with example 1 and assume that Z now requests 2 units and the

manager grants them.

- Currently the processes have 1, 5, and 12 units respectively.

- The manager has 4 units.

- The max additional needs are 2, 6, and 7.

- This state is unsafe

- Use 2 unit to satisfy X; now the manager has 5 units.

- Y needs 6 and Z needs 7 so we can't guarantee satisfying

either

- Note that we were able to find a process that can terminate

(X) but then we were stuck. So it is not enough to find one

process.

We must find a sequence of all the processes.

Remark: Discuss the diagram above (before the

examples) explaining why can't tell safety without initial claims.

Remark: Lab 3 (banker) assigned.

It is due in 2 weeks.

Remark: An unsafe state is not

necessarily a deadlocked state.

Indeed, if one gets lucky all processes in an unsafe state may

terminate successfully.

A safe state means that the manager can

guarantee that no deadlock will occur.

3.5.3: The Banker's Algorithm (Dijkstra) for a Single Resource

The algorithm is simple: Stay in safe states. Initially, we

assume all the processes are present before execution begins and that

all initial claims are given before execution begins.

We will relax these assumptions very soon.

- Before execution begins, check that the system is safe.

That is, check that no process claims more than the manager has).

If not, then the offending process is trying to claim more of

some resource than exist in

the system has and hence cannot be guaranteed to complete even if

run by itself.

You might say that it can become deadlocked all by itself.

- When the manager receives a request, it pretends to grant

it and checks if the resulting state is safe.

If it is safe the request is granted, if not the process is

blocked.

- When a resource is returned, the manager (politely thanks the

process and then) checks to see if “the first” pending

requests can be granted (i.e., if the result would now be

safe).

If so the request is granted.

Whether or not the request was granted, the manager checks to see if

the next pending request can be granted, etc..

Homework: 13.

3.5.4: The Banker's Algorithm for Multiple Resources

At a high level the algorithm is identical: Stay in safe states.

- What is a safe state?

- The same definition (if processes are run in a certain

order they will all terminate).

-

Checking for safety is the same idea as above.

The difference is that to tell if there are enough free resources

for a processes to terminate, the manager must check that

for all resources, the number of free units is at

least equal to the max additional need of the process.

Limitations of the banker's algorithm

- Often users don't know the maximum requests a process will make.

They can estimate conservatively (i.e., use big numbers for the claim)

but then the manager becomes very conservative.

- New processes arriving cause a problem (but not so bad as

Tanenbaum suggests).

- The process's claim must be less than the total number of

units of the resource in the system. If not, the process is not

accepted by the manager.

- Since the state without the new process is safe, so is the

state with the new process! Just use the order you had originally

and put the new process at the end.

- Insuring fairness (starvation freedom) needs a little more

work, but isn't too hard either (once an hour stop taking new

processes until all current processes finish).

- A resource can become unavailable (e.g., a tape drive might

break).

This can result in an unsafe state.

Homework: 21, 27, and 20. There is an interesting

typo in 20: A has claimed 3 units of resource 5,

but there are only 2 units in the entire system.

Change the problem by having B both claim and be allocated 1 unit of

resource 5.

3.7: Other Issues

3.7.1: Two-phase locking

This is covered (MUCH better) in a database text. We will skip it.

3.7.2: Non-resource deadlocks

You can get deadlock from semaphores as well as resources. This is

trivial. Semaphores can be considered resources. P(S) is request S

and V(S) is release S. The manager is the module implementing P and

V. When the manager returns from P(S), it has granted the resource S.

3.7.3: Starvation

As usual FCFS is a good cure. Often this is done by priority aging

and picking the highest priority process to get the resource. Also

can periodically stop accepting new processes until all old ones

get their resources.

3.8: Research on Deadlocks

Skipped.

3.9: Summary

Read.

Chapter 4: Memory Management

Also called storage management or

space management.

Memory management must deal with the storage

hierarchy present in modern machines.

-

Registers, cache, central memory, disk, tape (backup)

-

Move data from level to level of the hierarchy.

-

How should we decide when to move data up to a higher level?

- Fetch on demand (e.g. demand paging, which is dominant now).

- Prefetch

- Read-ahead for file I/O.

- Large cache lines and pages.

- Extreme example. Entire job present whenever running.

We will see in the next few weeks that there are three independent

decision:

-

Segmentation (or no segmentation)

-

Paging (or no paging)

-

Fetch on demand (or no fetching on demand)

Memory management implements address translation.

-

Convert virtual addresses to physical addresses

- Also called logical to real address translation.

- A virtual address is the address expressed in

the program.

- A physical address is the address understood

by the computer hardware.

-

The translation from virtual to physical addresses is performed by

the Memory Management Unit or (MMU).

-

Another example of address translation is the conversion of

relative addresses to absolute addresses

by the linker.

-

The translation might be trivial (e.g., the identity) but not in a modern

general purpose OS.

-

The translation might be difficult (i.e., slow).

- Often includes addition/shifts/mask--not too bad.

- Often includes memory references.

- VERY serious.

- Solution is to cache translations in a Translation

Lookaside Buffer (TLB). Sometimes called a

translation buffer (TB).

Homework: 6.

When is address translation performed?

-

At compile time

- Compiler generates physical addresses.

- Requires knowledge of where the compilation unit will be loaded.

- No linker.

- Loader is trivial.

- Primitive.

- Rarely used (MSDOS .COM files).

-

At link-edit time (the “linker lab”)

- Compiler

-

Generates relative (a.k.a. relocatable) addresses for each

compilation unit.

-

References external addresses.

- Linkage editor

- Converts the relocatable addr to absolute.

- Resolves external references.

-

Misnamed ld by unix.

-

Must also converts virtual to physical addresses by

knowing where the linked program will be loaded. Linker

lab “does” this, but it is trivial since we

assume the linked program will be loaded at 0.

-

Loader is still trivial.

-

Hardware requirements are small.

-

A program can be loaded only where specified and

cannot move once loaded.

-

Not used much any more.

-

At load time

-

Similar to at link-edit time, but do not fix

the starting address.

-

Program can be loaded anywhere.

-

Program can move but cannot be split.

-

Need modest hardware: base/limit registers.

-

Loader sets the base/limit registers.

-

No longer common.

-

At execution time

- Addresses translated dynamically during execution.

- Hardware needed to perform the virtual to physical address

translation quickly.

- Currently dominates.

- Much more information later.

Extensions

-

Dynamic Loading

- When executing a call, check if module is loaded.

- If not loaded, call linking loader to load it and update

tables.

- Slows down calls (indirection) unless you rewrite code dynamically.

- Not used much.

-

Dynamic Linking

- The traditional linking described above is today often called

static linking.

- With dynamic linking, frequently used routines are not linked

into the program. Instead, just a stub is linked.

- When the routine is called, the stub checks to see if the

real routine is loaded (it may have been loaded by

another program).

- If not loaded, load it.

- If already loaded, share it. This needs some OS

help so that different jobs sharing the library don't

overwrite each other's private memory.

- Advantages of dynamic linking.

- Saves space: Routine only in memory once even when used

many times.

- Bug fix to dynamically linked library fixes all applications

that use that library, without having to

relink the application.

- Disadvantages of dynamic linking.

- New bugs in dynamically linked library infect all

applications.

- Applications “change” even when they haven't changed.

Is the figure on the right safe or not?

Is the figure on the right safe or not?