Remark: Homework solutions will be posted (probably tomorrow). In fact homework #1 solution is already there.

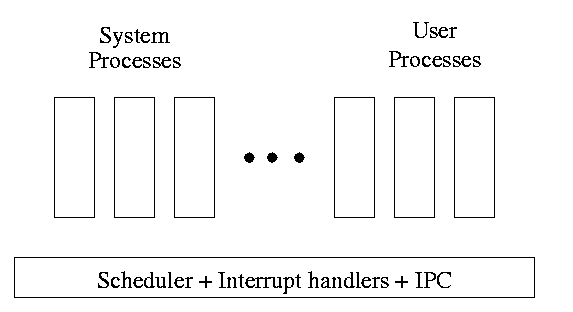

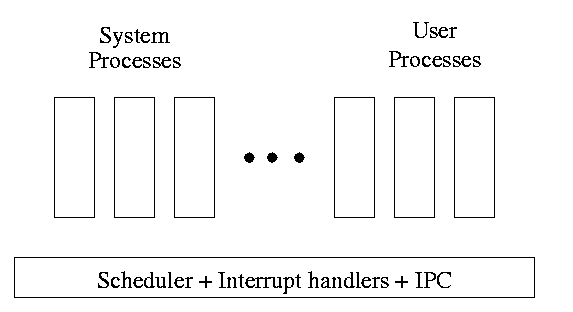

One can organize an OS around the scheduler.

The OS organizes the data about each process in a table naturally called the process table. Each entry in this table is called a process table entry (PTE) or process control block.

In a well defined location in memory (specified by the hardware) the OS stores an interrupt vector, which contains the address of the (first level) interrupt handler.

Assume a process P is running and a disk interrupt occurs for the completion of a disk read previously issued by process Q, which is currently blocked. Note that disk interrupts are unlikely to be for the currently running process (because the process that initiated the disk access is likely blocked).

| Per process items | Per thread items |

|---|---|

| Address space | Program counter |

| Global variables | Machine registers |

| Open files | Stack |

| Child processes | |

| Pending alarms | |

| Signals and signal handlers | |

| Accounting information |

The idea is to have separate threads of control (hence the name) running in the same address space. An address space is a memory management concept. For now think of an address space as the memory in which a process runs and the mapping from the virtual addresses (addresses in the program) to the physical addresses (addresses in the machine). Each thread is somewhat like a process (e.g., it is scheduled to run) but contains less state (e.g., the address space belongs to the process in which the thread runs.

A process contains a number of resources such as address space, open files, accounting information, etc. In addition to these resources, a process has a thread of control, e.g., program counter, register contents, stack. The idea of threads is to permit multiple threads of control to execute within one process. This is often called multithreading and threads are often called lightweight processes. Because threads in the same process share so much state, switching between them is much less expensive than switching between separate processes.

Individual threads within the same process are not completely independent. For example there is no memory protection between them. This is typically not a security problem as the threads are cooperating and all are from the same user (indeed the same process). However, the shared resources do make debugging harder. For example one thread can easily overwrite data needed by another and if one thread closes a file other threads can't read from it.

Often, when a process A is blocked (say for I/O) there is still computation that can be done. Another process B can't do this computation since it doesn't have access to the A's memory. But two threads in the same process do share memory so there is no problem.

An important modern example is a multithreaded web server. Each thread is

responding to a single WWW connection. While one thread is blocked on

I/O, another thread can be processing another WWW connection. Why not

use separate processes, i.e., what is the shared memory?

Ans: The cache of frequently referenced pages.

A common organization is to have a dispatcher thread that fields requests and then passes this request on to an idle thread.

Another example is a producer-consumer problem (c.f. below) in which we have 3 threads in a pipeline. One reads data, the second processes the data read, and the third outputs the processed data. Again, while one thread is blocked the others can execute.

Homework: 9.

Write a (threads) library that acts as a mini-scheduler and implements thread_create, thread_exit, thread_wait, thread_yield, etc. The central data structure maintained and used by this library is the thread table, the analogue of the process table in the operating system itself.

Advantages

Disadvantages

Move the thread operations into the operating system itself. This naturally requires that the operating system itself be (significantly) modified and is thus not a trivial undertaking.

One can write a (user-level) thread library even if the kernel also has threads. This is sometimes called the M:N model since M user mode threads run on each of N kernel threads. Then each kernel thread can switch between user level threads. Thus switching between user-level threads within one kernel thread is very fast (no context switch) and we maintain the advantage that a blocking system call or page fault does not block the entire multi-threaded application.

Skipped

The idea is to automatically issue a create thread system call upon message arrival. (The alternative is to have a thread or process blocked on a receive system call.) If implemented well the latency between message arrival and thread execution can be very small since the new thread does not have state to restore.

Definitely NOT for the faint of heart.

A race condition occurs when two processes can interact and the outcome depends on the order in which the processes execute.

Imagine two processes both accessing x, which is initially 10.

We must prevent interleaving sections of code that need to be atomic with respect to each other. That is, the conflicting sections need mutual exclusion. If process A is executing its critical section, it excludes process B from executing its critical section. Conversely if process B is executing is critical section, it excludes process A from executing its critical section.

Requirements for a critical section implementation.

The operating system can choose not to preempt itself. That is, we do not preempt system processes (if the OS is client server) or processes running in system mode (if the OS is self service). Forbidding preemption for system processes would prevent the problem above where x<--x+1 not being atomic crashed the printer spooler if the spooler is part of the OS.

But simply forbidding preemption while in system mode is not sufficient.

Initially P1wants=P2wants=false

Code for P1 Code for P2

Loop forever { Loop forever {

P1wants <-- true ENTRY P2wants <-- true

while (P2wants) {} ENTRY while (P1wants) {}

critical-section critical-section

P1wants <-- false EXIT P2wants <-- false

non-critical-section } non-critical-section }

Explain why this works.

But it is wrong! Why?

Let's try again. The trouble was that setting want before the loop permitted us to get stuck. We had them in the wrong order!

Initially P1wants=P2wants=false

Code for P1 Code for P2

Loop forever { Loop forever {

while (P2wants) {} ENTRY while (P1wants) {}

P1wants <-- true ENTRY P2wants <-- true

critical-section critical-section

P1wants <-- false EXIT P2wants <-- false

non-critical-section } non-critical-section }

Explain why this works.

But it is wrong again! Why?

So let's be polite and really take turns. None of this wanting stuff.

Initially turn=1

Code for P1 Code for P2

Loop forever { Loop forever {

while (turn = 2) {} while (turn = 1) {}

critical-section critical-section

turn <-- 2 turn <-- 1

non-critical-section } non-critical-section }

This one forces alternation, so is not general enough. Specifically, it does not satisfy condition three, which requires that no process in its non-critical section can stop another process from entering its critical section. With alternation, if one process is in its non-critical section (NCS) then the other can enter the CS once but not again.

In fact, it took years (way back when) to find a correct solution. Many earlier ``solutions'' were found and several were published, but all were wrong. The first correct solution was found by a mathematician named Dekker, who combined the ideas of turn and wants. The basic idea is that you take turns when there is contention, but when there is no contention, the requesting process can enter. It is very clever, but I am skipping it (I cover it when I teach distributed operating systems in V22.0480 or G22.2251). Subsequently, algorithms with better fairness properties were found (e.g., no task has to wait for another task to enter the CS twice).

What follows is Peterson's solution, which also combines turn and wants to force alternation only when there is contention. When Peterson's solution was published, it was a surprise to see such a simple soluntion. In fact Peterson gave a solution for any number of processes. A proof that the algorithm satisfies our properties (including a strong fairness condition) for any number of processes can be found in Operating Systems Review Jan 1990, pp. 18-22.

Initially P1wants=P2wants=false and turn=1

Code for P1 Code for P2

Loop forever { Loop forever {

P1wants <-- true P2wants <-- true

turn <-- 2 turn <-- 1

while (P2wants and turn=2) {} while (P1wants and turn=1) {}

critical-section critical-section

P1wants <-- false P2wants <-- false

non-critical-section non-critical-section