================ Start Lecture #13

================

Chapter 6: File Systems

Requirements

- Size: Store very large amounts of data.

- Persistence: Data survives the creating process.

- Access: Multiple processes can access the data concurrently.

Solution: Store data in files that together form a file system.

6.1: Files

6.1.1: File Naming

Very important. A major function of the file system.

- Does each file have a unique name?

Answer: Often no. We will discuss this below when we study

links.

- Extensions, e.g. the ``html'' in ``class-notes.html''.

- Conventions just for humans: letter.teq (my convention).

- Conventions giving default behavior for some programs.

- The emacs editor thinks .html files should be edited in

html mode but

can edit them in any mode and can edit any file

in html mode.

- Netscape thinks .html means an html file, but

<html> ... </html> works as well

- Gzip thinks .gz means a compressed file but accepts a

--suffix flag

- Default behavior for Operating system or window manager or

desktop environment.

- Click on .xls file in windows and excel is started.

- Click on .xls file in nautilus under linux and gnumeric is

started.

- Required extensions for programs

- The gnu C compiler (and probably others) requires C

programs be named *.c and assembler programs be named *.s

- Required extensions by operating systems

- MS-DOS treats .com files specially

- Windows 95 requires (as far as I can tell) shortcuts to

end in .lnk.

- Case sensitive?

Unix: yes. Windows: no.

6.1.2: File structure

A file is a

- Byte stream

- Unix, dos, windows (I think).

- Maximum flexibility.

- Minimum structure.

- (fixed size) Record stream: Out of date

- 80-character records for card images.

- 133-character records for line printer files. Column 1 was

for control (e.g., new page) Remaining 132 characters were printed.

- Varied and complicated beast.

- Indexed sequential.

- B-trees.

- Supports rapidly finding a record with a specific

key.

- Supports retrieving (varying size) records in key order.

- Treated in depth in database courses.

6.1.3: File types

Examples

- (Regular) files.

- Directories: studied below.

- Special files (for devices).

Uses the naming power of files to unify many actions.

dir # prints on screen

dir > file # result put in a file

dir > /dev/tape # results written to tape

- ``Symbolic'' Links (similar to ``shortcuts''): Also studied

below.

``Magic number'': Identifies an executable file.

- There can be

several different magic numbers for different types of

executables.

- unix: #!/usr/bin/perl

Strongly typed files:

- The type of the file determines what you can do with the

file.

- This make the easy and (hopefully) common case easier and, more

importantly safer.

- It tends to make the unusual case harder. For example, you have a

program that turns out data (.dat) files. But you want to use it to

turn out a java file but the type of the output is data and cannot be

easily converted to type java.

6.1.4: File access

There are basically two possibilities, sequential access and random

access (a.k.a. direct access).

Previously, files were declared to be sequential or random.

Modern systems do not do this.

Instead all files are random and optimizations are applied when the

system dynamically determines that a file is (probably) being accessed

sequentially.

- With Sequential access the bytes (or records)

are accessed in order (i.e., n-1, n, n+1, ...).

Sequential access is the most common and

gives the highest performance.

For some devices (e.g. tapes) access ``must'' be sequential.

- With random access, the bytes are accessed in any

order. Thus each access must specify which bytes are desired.

6.1.5: File attributes

A laundry list of properties that can be specified for a file

For example:

- hidden

- do not dump

- owner

- key length (for keyed files)

6.1.6: File operations

- Create:

Essential if a system is to add files. Need not be a separate system

call (can be merged with open).

- Delete:

Essential if a system is to delete files.

- Open:

Not essential. An optimization in which the translation from file name to

disk locations is perform only once per file rather than once per access.

- Close:

Not essential. Free resources.

- Read:

Essential. Must specify filename, file location, number of bytes,

and a buffer into which the data is to be placed.

Several of these parameters can be set by other

system calls and in many OS's they are.

- Write:

Essential if updates are to be supported. See read for parameters.

- Seek:

Not essential (could be in read/write). Specify the

offset of the next (read or write) access to this file.

- Get attributes:

Essential if attributes are to be used.

- Set attributes:

Essential if attributes are to be user settable.

- Rename:

Tanenbaum has strange words. Copy and delete is not acceptable for

big files. Moreover copy-delete is not atomic. Indeed link-delete is

not atomic so even if link (discussed below)

is provided, renaming a file adds functionality.

Homework: 6, 7.

6.1.7: An Example Program Using File System Calls

Homework: Read and understand ``copyfile''.

Notes on copyfile

- Normally in unix one wouldn't call read and write directly.

- Indeed, for copyfile, getchar() and putchar() would be nice since

they take care of the buffering (standard I/O, stdio).

- If you compare copyfile from the 1st to 2nd edition, you can see

the addition of error checks.

6.1.7: Memory mapped files (Unofficial)

Conceptually simple and elegant. Associate a segment with each

file and then normal memory operations take the place of I/O.

Thus copyfile does not have fgetc/fputc (or read/write). Instead it is

just like memcopy

while ( *(dest++) = *(src++) );

The implementation is via segmentation with demand paging but

the backing store for the pages is the file itself.

This all sounds great but ...

- How do you tell the length of a newly created file? You know

which pages were written but not what words in those pages. So a file

with one byte or 10, looks like a page.

- What if same file is accessed by both I/O and memory mapping.

- What if the file is bigger than the size of virtual memory (will

not be a problem for systems built 3 years from now as all will have

enormous virtual memory sizes).

6.2: Directories

Unit of organization.

6.2.1-3: Single-level, Two-level, and Hierarchical directory systems

Possibilities

- One directory in the system (Single-level)

- One per user and a root above these (Two-level)

- One tree

- One tree per user

- One forest

- One forest per user

These are not as wildly different as they sound.

- If the system only has one directory, but allows the character / in

a file name. Then one could fake a tree by having a file named

/allan/gottlieb/courses/arch/class-notes.html

rather than a directory allan, a subdirectory gottlieb, ..., a file

class-notes.html.

- Dos (windows) is a forest, unix a tree. In dos there is no common

parent of a:\ and c:\.

- But windows explorer makes the dos forest look quite a bit like a

tree. Indeed, the original gnome file manager for linux, looks A LOT

like windows explorer.

- You can get an effect similar to (but not the same as) one X per

user by having just one X in the system and having permissions that

permits each user to visit only a subset. Of course if the system

doesn't have permissions, this is not possible.

- Today's systems have a tree per system or a forest per system.

6.2.4: Path Names

You can specify the location of a file in the file hierarchy by

using either an absolute versus or a

Relative path to the file

- An absolute path starts at the (or a if we have a forest) root.

- A relative path starts at the

current (a.k.a working) directory.

- The special directories . and .. represent the current directory

and the parent of the current directory respectively.

Homework: 1, 9.

6.2.5: Directory operations

- Create: Produces an ``empty'' directory.

Normally the directory created actually contains . and .., so is not

really empty

- Delete: Requires the directory to be empty (i.e., to just contain

. and ..). Commands are normally written that will first empty the

directory (except for . and ..) and then delete it. These commands

make use of file and directory delete system calls.

- Opendir: Same as for files (creates a ``handle'')

- Closedir: Same as for files

- Readdir: In the old days (of unix) one could read directories as files

so there was no special readdir (or opendir/closedir). It was

believed that the uniform treatment would make programming (or at

least system understanding) easier as there was less to learn.

However, experience has taught that this was not a good idea since

the structure of directories then becomes exposed. Early unix had a

simple structure (and there was only one). Modern systems have more

sophisticated structures and more importantly they are not fixed

across implementations.

- Rename: As with files

- Link: Add a second name for a file; discussed

below.

- Unlink: Remove a directory entry. This is how a file is deleted.

But if there are many links and just one is unlinked, the file

remains. Discussed in more

detail below.

6.3: File System Implementation

6.3.1: File System Layout

- One disk starts with a Master Boot Record (MBR).

- Each disk has a partition table.

- Each partition holds one file system.

- Each partition typically contains some parameters (e.g., size),

free blocks, and blocks in use. The details vary.

- In unix some of the in use blocks contains I-nodes each of which

describes a file (or directory and is described below)

- During boot the MBR is read and executed. It transfers control to

the boot block of the active partition.

6.3.2; Implementing Files

- A disk cannot read or write a single word. Instead it can read or

write a sector, which is often 512 bytes.

- Disks are written in blocks whose size is a multiple of the sector

size.

- When we study I/O in the next chapter I will bring in some

physically large (and hence old) disks so that we can see what they

look like and understand better sectors (and tracks, and cylinders,

and heads, etc.).

Contiguous allocation

- This is like OS/MVT.

- The entire file is stored as one piece.

- Simple and fast for access, but ...

- Problem with growing files

- Must either evict the file itself or the file it is bumping

into.

- Same problem with an OS/MVT kind of system if jobs grow.

- Problem with external fragmentation.

- Not used for general purpose systems. Ideal for systems where

files do not change size.

Homework: 12.

Linked allocation

- The directory entry contains a pointer to the first block of the file.

- Each block contains a pointer to the next.

- Horrible for random access.

- Not used.

FAT (file allocation table)

- Used by dos and windows (but not windows/NT).

- Directory entry points to first block (i.e. specifies the block

number).

- A FAT is maintained in memory having one (word) entry for each

disk block. The entry for block N contains the block number of the

next block in the same file as N.

- This is linked but the links are store separately.

- Time to access a random block is still is linear in size of file

but now all the references are to this one table which is in memory.

So it is bad but not horrible for random access.

- Size of table is one word per disk block. If one writes all

blocks of size 4K and uses 4-byte words, the table is one megabyte for

each disk gigabyte. Large but not prohibitive.

- If write blocks of size 512 bytes (the sector size of most disks)

then the table is 8 megs per gig, which might be prohibitive.

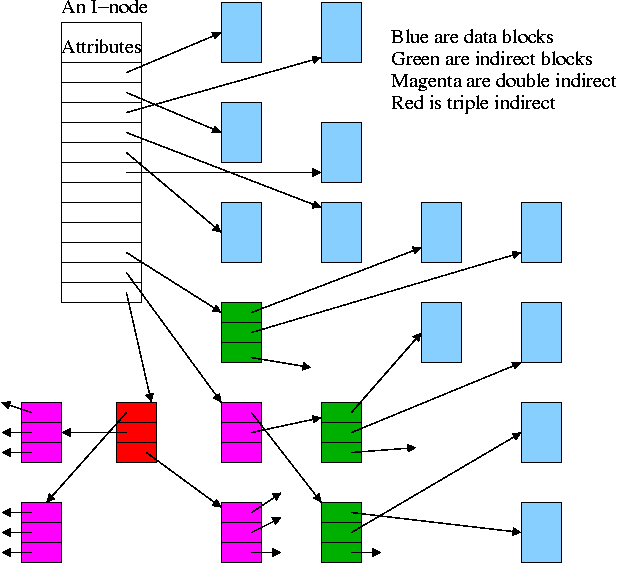

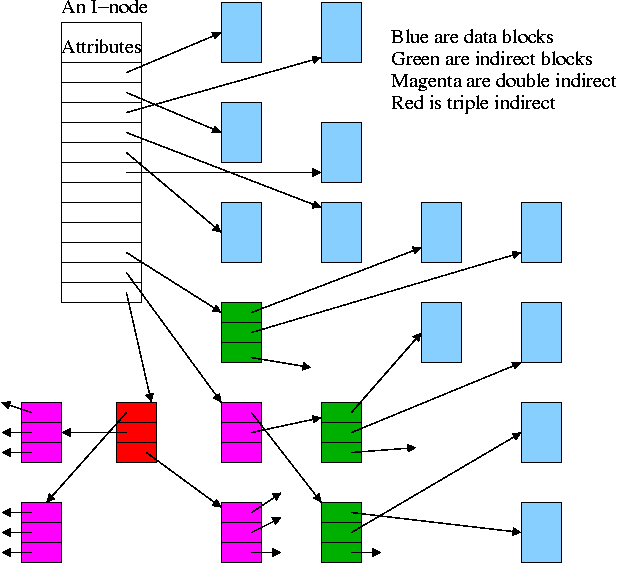

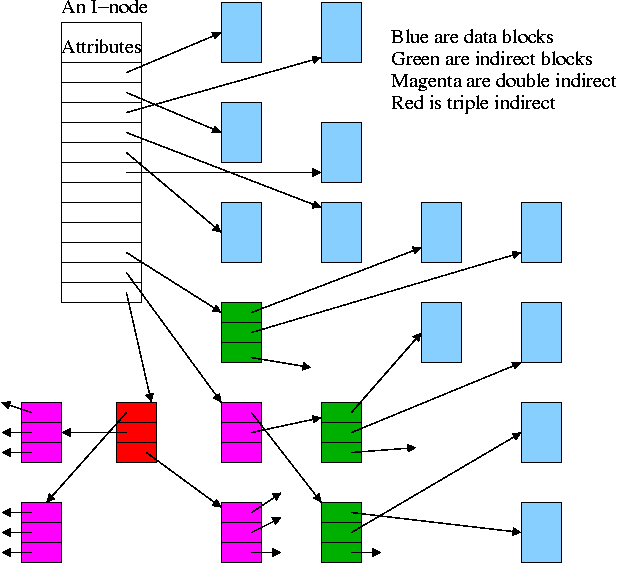

Inodes

- Used by unix.

- Directory entry points to inode (index-node).

- Inode points to first few data blocks, often called direct blocks.

- Inode also points to an indirect block, which points to disk blocks.

- Inode also points to a double indirect, which points an indirect ...

- For some implementations there are triple indirect as well.

- The inode is in memory for open files.

So references to direct blocks take just one I/O.

- For big files most references require two I/Os (indirect + data).

- For huge files most references require three I/Os (double

indirect, indirect, and data).

6.3.3: Implementing Directories

Recall that a directory is a mapping that converts file (or

subdirectory) names to the files (or subdirectories) themselves.

Trivial File System (CP/M)

- Only one directory in the system.

- Directory entry contains pointers to disk blocks.

- If need more blocks, get another directory entry.

MS-DOS and Windows (FAT)

- Subdirectories supported.

- Directory entry contains metatdata such as date and size

as well as pointer to first block.

Unix

- Each entry contains a name and a pointer to the corresponding inode.

- Metadata is in the inode.

- Early unix had limit of 14 character names.

- Name field now is varying length.

- To go down a level in directory takes two steps: get inode, get

file (or subdirectory).

- Do on the blackboard the steps for

/allan/gottlieb/courses/os/class-notes.html

Homework: 27

6.3.4: Shared files (links)

- ``Shared'' files is Tanenbaum's terminology.

- More descriptive would be ``multinamed files''.

- If a file exists, one can create another name for it (quite

possibly in another directory).

- This is often called creating a (or another) link to the file.

- Unix has two flavor of links, hard links and

symbolic links or symlinks.

- Dos/windows has symlinks, but I don't believe it has hard links.

- These links often cause confusion, but I really believe that the

diagrams I created make it all clear.

Hard Links

- Symmetric multinamed files.

- When a hard like is created another name is created for

the same file.

- The two names have equal status.

- It is not, I repeat NOT true that one

name is the ``real name'' and the other one is ``just a link''.

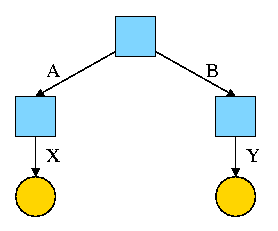

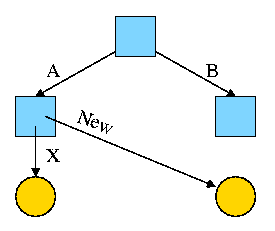

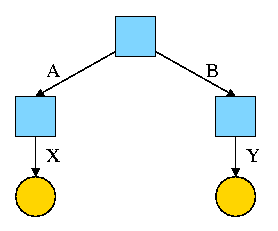

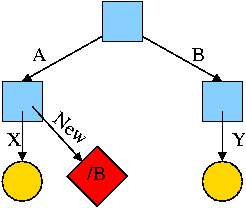

Start with an empty file system (i.e., just the root directory) and

then execute:

cd /

mkdir /A; mkdir /B

touch /A/X; touch /B/Y

We have the situation shown on the right.

Note that names are on edges not nodes.

When there are no multinamed files, it doesn't much matter.

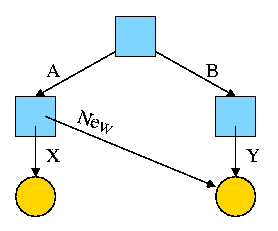

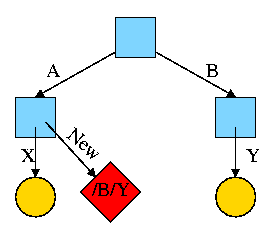

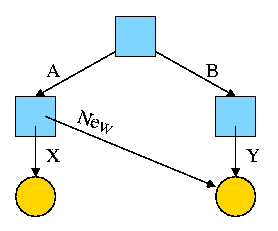

Now execute

ln /B/Y /A/New

This gives the new diagram to the right.

At this point there are two equally valid name for the right hand

yellow file, /B/Y and /A/New. The fact that /B/Y was created first is

NOT detectable.

- Both point to the same inode.

- Only one owner (the one who created the file initially).

- One date, one set of permissions, one ... .

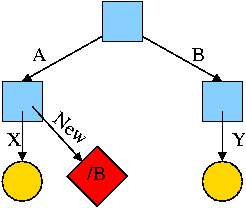

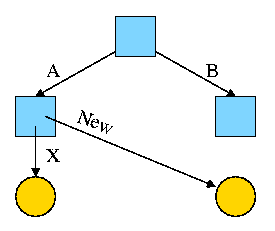

Assume Bob created /B and /B/Y and Alice created /A, /A/X, and /A/New.

Later Bob tires of /B/Y and removes it by executing

rm /B/Y

The file /A/New is still fine (see third diagram on the right).

But it is owned by Bob, who can't find it! If the system enforces

quotas bob will likely be charged (as the owner), but he can neither

find nor delete the file (since bob cannot unlink, i.e. remove, files

from /A)

Since hard links are only permitted to files (not directories) the

resulting file system is a dag (directed acyclic graph). That is, there

are no directed cycles. We will now proceed to give away this useful

property by studying symlinks, which can point to directories.

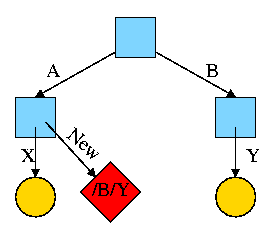

Symlinks

- Asymmetric multinamed files.

- When a symlink is created another file is created, one

that points to the name of original file.

- A hard link in contrast points to the original

file.

The examples will make this clear.

Again start with an empty file system and this time execute

cd /

mkdir /A; mkdir /B

touch /A/X; touch /B/Y

ln -s /B/Y /A/New

We now have an additional file /A/New, which is a symlink to /B/Y.

- The file named /A/New has the name /B/Y as its data

(not metadata).

- The system notices that A/New is a diamond (symlink) so reading

/A/New will return the contents of /B/Y (assuming the reader has read

permission for /B/Y).

- If /B/Y is removed /A/New becomes invalid.

- If a new /B/Y is created, A/New is once again valid.

- Removing /A/New has no effect of /B/Y.

- If a user has write permission for /B/Y, then writing /A/New is possible

and writes /B/Y.

The bottom line is that, with a hard link, a new name is created

that has equal status to the original name. This can cause some

surprises (e.g., you create a link but I own the file).

With a symbolic link a new file is created (owned by the

creator naturally) that points to the original file.

Question: Consider the hard link setup above. If Bob removes /B/Y

and then creates another /B/Y, what happens to /A/New?

Answer: Nothing. /A/New is still a file with the same contents as the

original /B/Y.

Question: What about with a symlink?

Answer: /A/New becomes invalid and then valid again, this time pointing

to the new /B/Y.

(It can't point to the old /B/Y as that is completely gone.)

Note:

Shortcuts in windows contain more that symlinks in unix. In addition

to the file name of the original file, they can contain arguments to

pass to the file if it is executable. So a shortcut to

netscape.exe

can specify

netscape.exe //allan.ultra.nyu.edu/~gottlieb/courses/os/class-notes.html

End of Note

What about symlinking a directory?

cd /

mkdir /A; mkdir /B

touch /A/X; touch /B/Y

ln -s /B /A/New

Is there a file named /A/New/Y ?

Yes.

What happens if you execute cd /A/New/.. ?

- Answer: Not clear!

- Clearly you are changing directory to the parent directory of

/A/New. But is that /A or /?

- The command interpreter I use offers both possibilities.

- cd -L /A/New/.. takes you to A (L for logical).

- cd -P /A/New/.. takes you to / (P for physical).

- cd /A/New/.. takes you to A (logical is the default).

What did I mean when I said the pictures made it all clear?

Answer: From the file system perspective it is clear. Not always so

clear what programs will do.