From the users or external viewpoint there are several mechanisms for creating a process.

- System initialization, including daemon processes.

- Execution of a process creation system call by a running process.

- A user request to create a new process.

- Initiation of a batch job.

But looked at internally, from the system's viewpoint, the second method dominates. Indeed in unix only one process is created at system initialization (the process is called init); all the others are children of this first process.

Why have init? That is why not have all processes created via

method 2?

Ans: Because without init there would be no running process to create

any others.

2.1.3: Process Termination

Again from the outside there appear to be several termination mechanism.

- Normal exit (voluntary).

- Error exit (voluntary).

- Fatal error (involuntary).

- Killed by another process (involuntary).

And again, internally the situation is simpler. In Unix terminology, there are two system calls kill and exit that are used. Kill (poorly named in my view) sends a signal to another process. If this signal is not caught (via the signal system call) the process is terminated. There is also an ``uncatchable'' signal. Exit is used for self termination and can indicate success or failure.

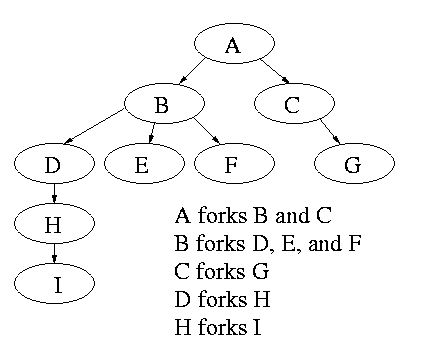

2.1.4: Process Hierarchies

Modern general purpose operating systems permit a user to create and destroy processes.

- In unix this is done by the fork system call, which creates a child process, and the exit system call, which terminates the current process.

- After a fork both parent and child keep running (indeed they have the same program text) and each can fork off other processes.

- A process tree results. The root of the tree is a special process created by the OS during startup.

- A process can choose to wait for children to terminate. For example, if C issued a wait() system call it would block until G finished.

Old or primitive operating system like

MS-DOS are not multiprogrammed so when one process starts another,

the first process is automatically blocked and waits until

the second is finished.

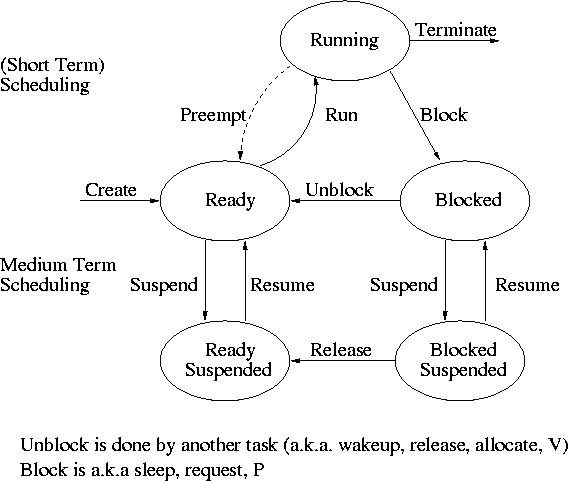

2.1.5: Process States and Transitions

The diagram on the right contains much information.

- Consider a running process P that issues an I/O request

- The process blocks

- At some later point, a disk interrupt occurs and the driver detects that P's request is satisfied.

- P is unblocked, i.e. is moved from blocked to ready

- At some later time the operating system looks for a ready job to run and picks P.

- A preemptive scheduler has the dotted line preempt;

A non-preemptive scheduler doesn't.

- The number of processes changes only for two arcs: create and

terminate.

- Suspend and resume are medium term scheduling

- Done on a longer time scale.

- Involves memory management as well.

- Sometimes called two level scheduling.

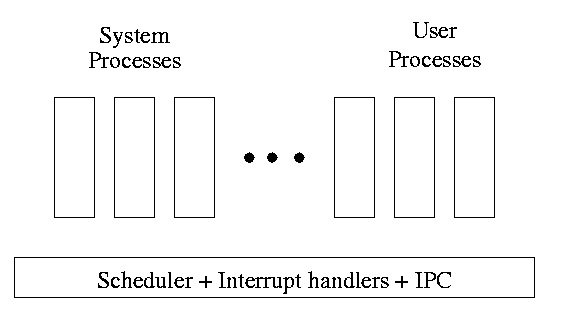

One can organize an OS around the scheduler.

- Write a minimal ``kernel'' consisting of the scheduler, interrupt handlers, and IPC (interprocess communication)

- The rest of the OS consists of kernel processes (e.g. memory, filesystem) that act as servers for the user processes (which of course act as clients.

- The system processes also act as clients (of other system processes).

- The above is called the client-server model and is one Tanenbaum likes. His ``Minix'' operating system works this way.

- Indeed, there was reason to believe that the client-server model would dominate OS design. But that hasn't happened.

- Such an OS is sometimes called server based.

-

Systems like traditional unix or linux would then be

called self-service since the user process serves itself.

- That is, the user process switches to kernel mode and performs the system call.

- To repeat: the same process changes back and forth from/to user<-->system mode and services itself.

2.1.6: Implementation of Processes

The OS organizes the data about each process in a table naturally called the process table. Each entry in this table is called a process table entry (PTE) or process control block.

- One entry per process.

- The central data structure for process management.

- A process state transition (e.g., moving from blocked to ready) is reflected by a change in the value of one or more fields in the PTE.

- We have converted an active entity (process) into a data structure (PTE). Finkel calls this the level principle ``an active entity becomes a data structure when looked at from a lower level''.

-

The PTE contains a great deal of information about the process.

For example,

- Saved value of registers when process not running

- Stack pointer

- CPU time used

- Process id (PID)

- Process id of parent (PPID)

- User id (uid and euid)

- Group id (gid and egid)

- Pointer to text segment (memory for the program text)

- Pointer to data segment

- Pointer to stack segment

- UMASK (default permissions for new files)

- Current working directory

- Many others

An aside on Interrupts (will be done again here)

In a well defined location in memory (specified by the hardware) the OS stores an interrupt vector, which contains the address of the (first level) interrupt handler.

- Tanenbaum calls the interrupt handler the interrupt service routine.

- Actually one can have different priorities of interrupts and the interrupt vector contains one pointer for each level. This is why it is called a vector.

Assume a process P is running and a disk interrupt occurs for the completion of a disk read previously issued by process Q, which is currently blocked. Note that interrupts are unlikely to be for the currently running process (because the process waiting for the interrupt is likely blocked).

- The hardware saves the program counter and some other registers (or switches to using another set of registers, the exact mechanism is machine dependent).

- Hardware loads new program counter from the interrupt vector.

- Loading the program counter causes a jump.

- Steps 1 and 2 are similar to a procedure call. But the interrupt is asynchronous.

- As with a trap (poof), the interrupt automatically switches the system into privileged mode.

- Assembly language routine saves registers.

- Assembly routine sets up new stack.

- These last two steps can be called setting up the C environment.

- Assembly routine calls C procedure (tanenbaum forgot this one).

- C procedure does the real work.

- Determines what caused the interrupt (in this case a disk

completed an I/O)

- How does it figure out the cause?

- Which priority interrupt was activated.

- The controller can write data in memory before the interrupt

- The OS can read registers in the controller

- How does it figure out the cause?

- Mark process Q as ready to run.

- That is move Q to the ready list (note that again we are viewing Q as a data structure).

- The state of Q is now ready (it was blocked before).

- The code that Q needs to run initially is likely to be OS code. For example, Q probably needs to copy the data just read from a kernel buffer into user space.

- Now we have at least two processes ready to run: P and Q

- Determines what caused the interrupt (in this case a disk

completed an I/O)

- The scheduler decides which process to run (P or Q or something else). Lets assume that the decision is to run P.

- The C procedure (that did the real work in the interrupt processing) continues and returns to the assembly code.

- Assembly language restores P's state (e.g., registers) and starts P at the point it was when the interrupt occurred.

2.2: Threads

| Per process items | Per thread items |

|---|---|

| Address space | Program counter |

| Global variables | Machine registers |

| Open files | Stack |

| Child processes | |

| Pending alarms | |

| Signals and signal handlers | |

| Accounting information |

The idea is to have separate threads of control (hence the name) running in the same address space. Each thread is somewhat like a process (e.g., it is scheduled to run) but contains less state (the address space belongs to the process in which the thread runs.

2.2.1: The Thread Model

A process contains a number of resources such as address space, open files, accounting information, etc. In addition to these resources, a process has a thread of control, e.g., program counter, register contents, stack. The idea of threads is to permit multiple threads of control to execute within one process. This is often called multithreading and threads are often called lightweight processes. Because the threads in a process share so much state, switching between them is much less expensive than switching between separate processes.

Individual threads within the same process are not completely independent. For example there is no memory protection between them. This is typically not a security problem as the threads are cooperating and all are from the same user (indeed the same process). However, the shared resources do make debugging harder. For example one thread can easily overwrite data needed by another and if one thread closes a file other threads can't read from it.

2.2.2: Thread Usage

Often, when a process A is blocked (say for I/O) there is still computation that can be done. Another process can't B do this computation since it doesn't have access to the A's memory. But two threads in the same process do share the memory so there is no problem.

An important example is a multithreaded web server. Each thread is

responding to a single WWW connection. While one thread is blocked on

I/O, another thread can be processing another WWW connection. Why not

use separate processes, i.e., what is the shared memory?

Ans: The cache of frequently referenced pages.

A common organization is to have a dispatcher thread that fields requests and then passes this request on to an idle thread.

Another example is a producer-consumer problem (c.f. below) in which we have 3 threads in a pipeline. One reads data, the second processes the data read, and the third outputs the processed data. Again, while one thread is blocked the others can execute.

Homework: 9.

2.2.3: Implementing threads in user space

Write a (threads) library that acts as a mini-scheduler and implements thread_create, thread_exit, thread_wait, thread_yield, etc. The central data structure maintained and used by this library is the thread table the analogue of the process table in the operating system itself.

Advantages

- Requires no OS modification.

- Very fast since no context switching.

- Can customize the scheduler for each application.

Disadvantages

- Re-doing the effort of writing a scheduler.

- Blocking systems can't be executed directly since that would block the entire process.

- Similarly a page fault would block the entire process.

- A thread with infinite loop prevents all other threads in this process from running.

2..2.4: Implementing Threads in the Kernel

Move the thread operations into the operating system itself. This naturally requires that the operating system itself be (significantly) modified and is thus not a trivial undertaking.

- Thread-create and friends are now systems and hence much slower.

- A thread that blocks causes no particular problem. The kernel can run another thread from this process or can run another process.

- Similarly a page fault in one thread does not automatically block the other threads in the process.

2.2.5: Hybrid Implementations

One can write a (user-level) thread library even if the kernel also has threads. Then each kernel thread can switch between user level threads.The threads in a kernel-level thread system can

2.2.6: Scheduler Activations

Skipped

2.2.7: Popup Threads

The idea is to automatically issue a create thread system call upon message arrival. (The alternative is to have a thread or process blocked on a receive system call.) If implemented well the latency between message arrival and thread execution can be very small since the new thread does not have state to restore.

Making Single-threaded Code Multithreaded

Definitely NOT for the faint of heart.

- There often is state that should not be shared. A well-cite example is the unix errno variable that contains the error number (zero means no error) of the error encountered by the last system call. Errno is hardly elegant, but its use is widespread. If multiple threads issue faulty system calls the errno value of the second overwrites the first and thus the first errno value may be lost.

- Much existing code, including many libraries, are not re-entrant.

- What should be done with a signal sent to a process. Does it go to all or one thread?

- How should stack growth be managed. Normally the kernel grows the (single) stack automatically when needed. What if there are multiple stacks?

2.3: Interprocess Communication (IPC) and Process Coordination and Synchronization

2.3.1: Race Conditions

A race condition occurs when two processes can interact and the outcome depends on the order in which the processes execute.

- Imagine two processes both accessing x, which is initially 10.

- One process is to execute x <-- x+1

- The other is to execute x <-- x-1

- When both are finished x should be 10

- But we might get 9 and might get 11!

- Show how this can happen (x <-- x+1 is not atomic)

- Tanenbaum shows how this can lead to disaster for a printer spooler

2.3.2: Critical sections

We must prevent interleaving sections of code that need to be atomic with respect to each other. That is, the conflicting sections need mutual exclusion. If process A is executing its critical section, it excludes process B from executing its critical section. Conversely if process B is executing is critical section, it excludes process A from executing its critical section.

Requirements for a critical section implementation.

- No two processes may be simultaneously inside their critical section.

- No assumption may be made about the speeds or the number of CPUs.

- No process outside its critical section may block other processes.

- No process should have to wait forever to enter its critical

section.

- I do NOT make this last requirement.

- I just require that the system as a whole make progress (so not all processes are blocked).

- I refer to solutions that do not satisfy Tanenbaum's last condition as unfair, but nonetheless correct, solutions.

- Stronger fairness conditions have also been defined.