There is not as much difference between mainframe, server, multiprocessor, and PC OSes as Tannenbaum suggests. For example Windows NT and 2000 are used in all (except mainframes) and Unix and Linux are used on all.

Used in data centers, these systems ofter tremendous I/O capabilities.

Perhaps the most important servers today are web servers. Again I/O (and network) performance are critical.

These existed almost from the beginning of the computer age, but now are not exotic.

Some OSes (e.g. Windows ME) are tailored for this application. One could also say they are restricted to this application.

Very limited in power (both meanings of the word).

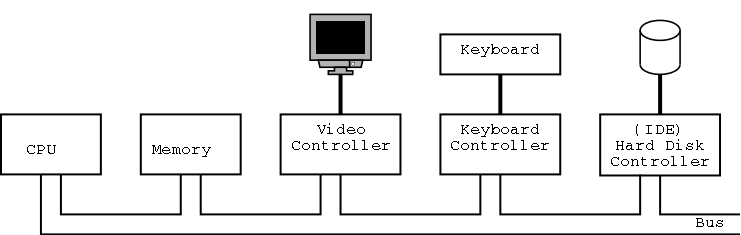

Tannenbaum's treatment is very brief and superficial. Mine is even more so. The picture on the right is very simplified. For one thing, today separate buses are used to Memory and Video.

We will ignore processor concepts such as program counters and stack pointers. We will also ignore computer design issues such as pipelining and superscalar. We do, however, need the notion of a trap, that is an instruction that atomically switches the processor into privileged mode and jumps to a pre-defined physical address.

We will ignore caches, but will (later) discuss demand paging, which is very similar although uses completely disjoint terminology. In both cases, the goal is to combine large slow memory with small fast memory and achieve the effect of large fast memory.

The central memory in a system is called RAM (Random Access Memory). A key point is that it is volatile, i.e. the memory loses its value if power is turned off.

I don't understand why Tanenbaum discusses disks here instead of in the next section entitled I/O devices, but he does. I don't.

ROM (Read Only Memory) is used to hold data that will not change, e.g. the serial number of a computer or the program use in a microwave. ROM is non-volatile.

But often this unchangable data needs to be changed (e.g., to fix bug). This gives rise first to PROM (Programmable ROM), which, like a CD-R, can be written once (as opposed to being mass produced already written like a CD-ROM), and then to EPROM (Erasable PROM; not Erasable ROM as in Tanenbaum), which is like a CD-RW. An EPROM is especially. convenient if it can be erased with a normal circuit (EEPROM, Electrically EPROM or Flash RAM).

As mentioned above when discussing OS/MFT and OS/MVT multiprograming requires that we protect one process from another. That is we need to translate the virtual addresses of each program into distinct physical addresses. The hardware that performs this translation is called the MMU or Memory Management Unit.

When context switching from one process to another, the translation must change, which can be an expensive operation.

Show a real disk opened up and illustrate the components

Devices are often quite complicated to manage and a separate computer, called a controller, is used to translate simple commands (read sector 123456) into what the device requires (read cylinder 321, head 6, sector 765). Actually the controller does considerably more, e.g. calculates a checksum for error detection.

How does the OS know when the I/O is complete?

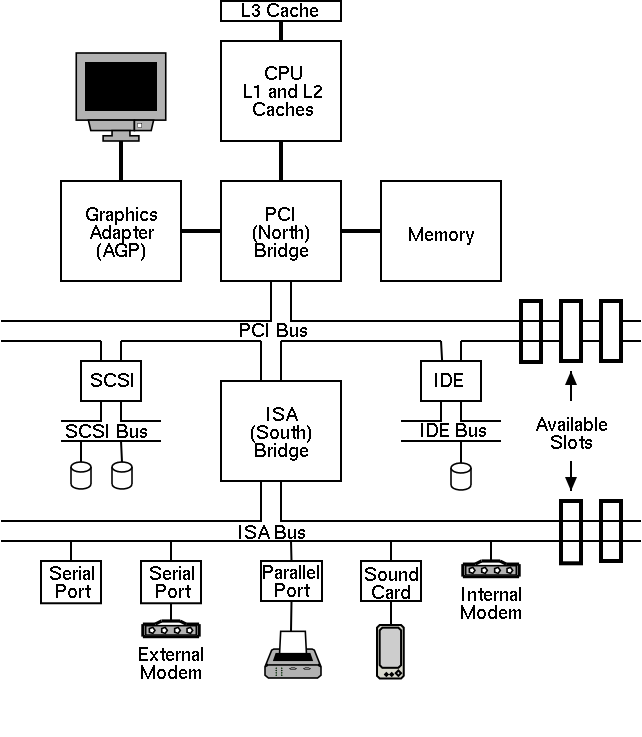

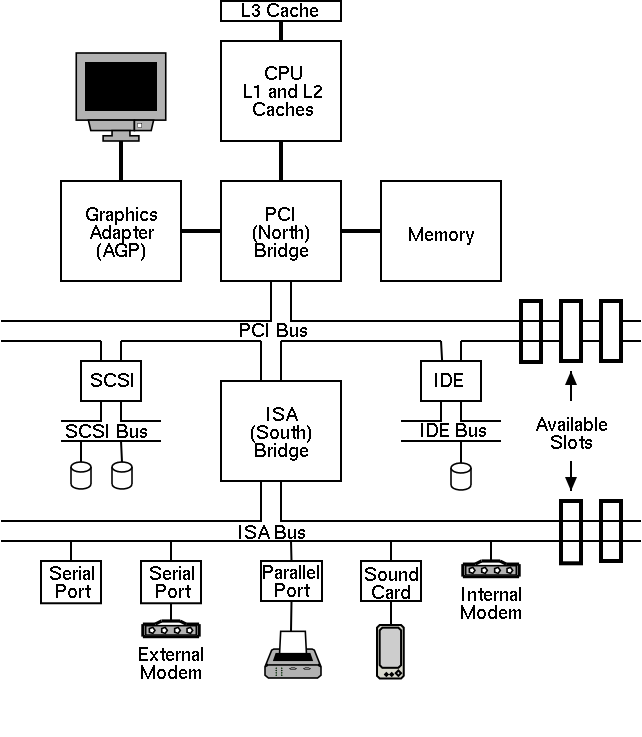

I don't care so much about the names of the buses, but the diagram

given in the book doesn't show a modern design. The one on the right

does.

This will be very brief. Much of the rest of the course will consist in ``filling in the details''.

A program in execution. If you run the same program twice, you have created two processes. For example if you have two editors running in two windows, each instance of the editor is a separate process.

Often one distinguishes the state or context (memory image, open files) from the thread of control. Then if one has many threads running in the same task, the result is a ``multithreaded processes''.

The OS keeps information about all processes in the process table. Indeed, the OS views the process as the entry. This is an example of an active entity being viewed as a data structure (cf. discrete event simulations). An observation made by Finkel in his (out of print) OS textbook.

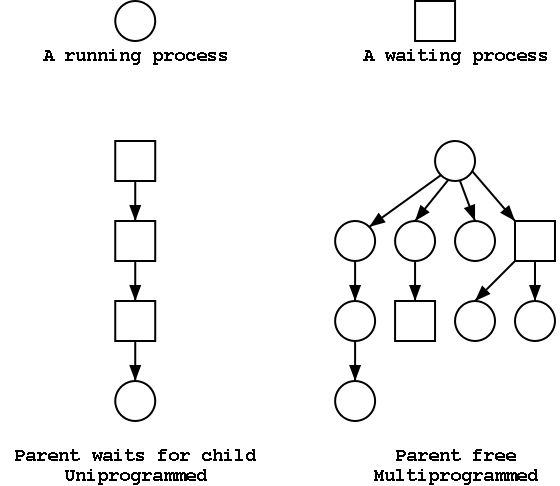

The set of processes forms a tree via the fork system call. The forker is the parent of the forkee, which is called a child. If the system blocks the parent until the child finishes, the ``tree'' is quite simple, just a line. But the parent (in many OSes) is free to continue executing and in particular is free to fork again producing another child.

A process can send a signal to another process to cause the latter to execute a predefined function (the signal handler). This can be tricky to program since the programmer does not know when in his ``main'' program the signal handler will be invoked.

Each user is assigned User IDentification (UID) and all processes created by that user have this UID. One UID is special (the superuser or administratore) and has extra privileges. A child has the same UID as its parent. It is sometimes possible to change the UID of a running process. A group of users can be formed and given a Group IDentification, GID.

Access to files and devices can be limited to a given UID or GID.

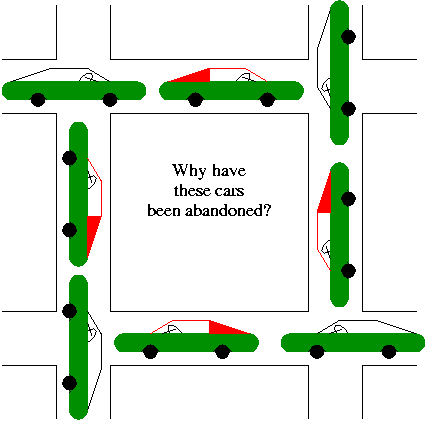

A set of processes each of which is blocked by a process in the

set. The automotive equivalent, shown at right, is gridlock.

Each process requires memory. The loader produces a load module that assumes the process is loaded at location 0. The operating system ensures that the processes are actually given disjoint memory. Current operating systems permit each process to be given more (virtual) memory than the total amount of (real) memory on the machine.

There are a wide variety of I/O devices that the OS must manage. For example, if two processes are printing at the same time, the OS must not interleave the output. The OS contains device specific code (drivers) for each device as well as device-independent I/O code.

Modern systems have a hierarchy of files. A file system tree.

You can name a file via an absolute path starting at the root directory or via a relative path starting at the current working directory.

In addition to regular files and directories, Unix also uses the file system namespace for devices (called special files, which are typically found in the /dev directory. Often utilities that are normally applied to (ordinary) files can be applied as well to some special files. For example, when you are accessing a unix system using a mouse and do not have anything serious going on (e.g., right after you log in), type the following command

cat /dev/mouse

and then move the mouse. You kill the cat by typing cntl-C. I tried

this on my linux box and no damage occurred. Your mileage may vary.

Before a file can be accessed, it must be opened and a file descriptor obtained. Many systems have standard files that are automatically made available to a process upon startup. These (initial) file descriptors are fixed

A convenience offered by some command interpretors is a pipe or pipeline. The pipeline

dir | wcwhich pipes the output dir into a character/word/line counter, will give the number of files in the directory (plus other info).

Files and directories normally have permissions

The command line interface to the operating system. The shell permits the user to

Homework: 8

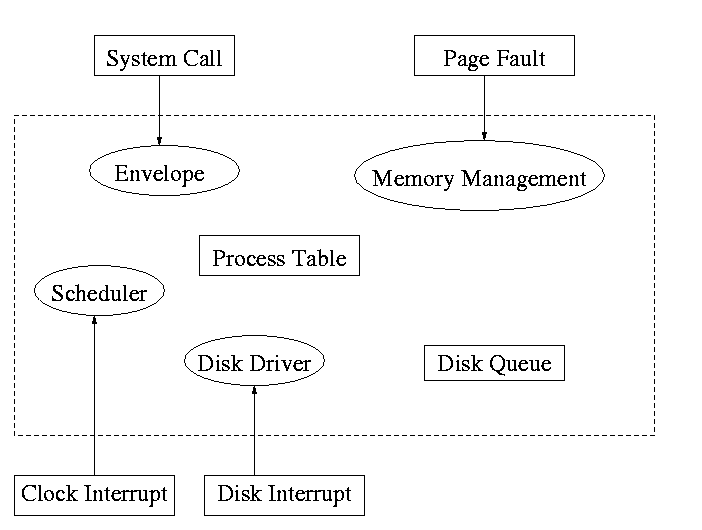

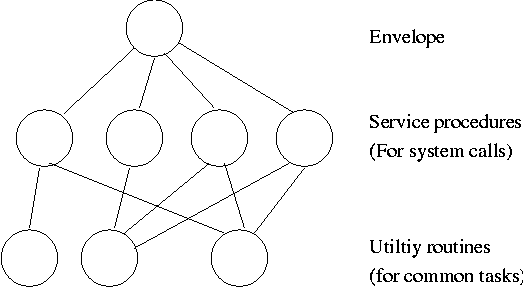

System calls are the way a user (i.e., a program) directly interfaces with the OS. Some textbooks use the term envelope for the component of the OS responsible for fielding system calls and dispatching them. On the right is a picture showing some of the OS components and the external events for which they are the interface.

Note that the OS serves two masters. The hardware (below) asynchronously sends interrupts and the user makes system calls and generates page faults.

Homework: 14

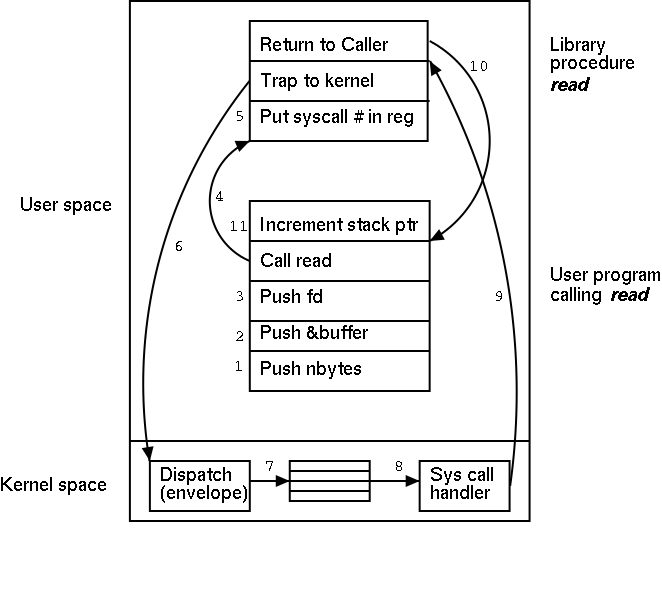

What happens when a user executes a system call such as read()?

We show a more detailed picture below, but at a high level what

happens is

The following actions occur when the user executes the (Unix)

system call

The following actions occur when the user executes the (Unix)

system call

count = read(fd,buffer,nbytes)which reads up to nbytes from the file described by fd into buffer. The actual number of bytes read is returned (it might be less than nbytes if, for example, an eof was encountered).

A major complication is that the system call handler may block.

Indeed for read it is likely. In that case a switch occurs to another

process. This is far from trivial and is discussed later in the course.

| Process Management | ||

|---|---|---|

| Posix | Win32 | Description |

| Fork | CreateProcess | Clone current process |

| exec(ve) | Replace current process | |

| waid(pid) | WaitForSingleObject | Wait for a child to terminate. |

| exit | ExitProcess | Terminate current process & return status |

| File Management | ||

| Posix | Win32 | Description |

| open | CreateFile | Open a file & return descriptor |

| close | CloseHandle | Close an open file |

| read | ReadFile | Read from file to buffer |

| write | WriteFile | Write from buffer to file |

| lseek | SetFilePointer | Move file pointer |

| stat | GetFileAttributesEx | Get status info |

| Directory and File System Management | ||

| Posix | Win32 | Description |

| mkdir | CreateDirectory | Create new directory |

| rmdir | RemoveDirectory | Remove empty directory |

| link | (none) | Create a directory entry |

| unlink | DeleteFile | Remove a directory entry |

| mount | (none) | Mount a file system |

| umount | (none) | Unmount a file system |

| Miscellaneous | ||

| Posix | Win32 | Description |

| chdir | SetCurrentDirectory | Change the current working directory |

| chmod | (none) | Change permissions on a file |

| kill | (none) | Send a signal to a process |

| time | GetLocalTime | Elapsed time since 1 jan 1970 |

The table on the right shows some systems calls; the descriptions are accurate for Unix and close for win32. To show how the four process management calls enable much of process management, consider the following highly simplified shell.

while (true)

display_prompt()

read_command(command)

if (fork() != 0) // true in parent false in child

waitpid(...)

else

execve(command) // the command itself executes exit()

endif

endwhile

Homework: 18.

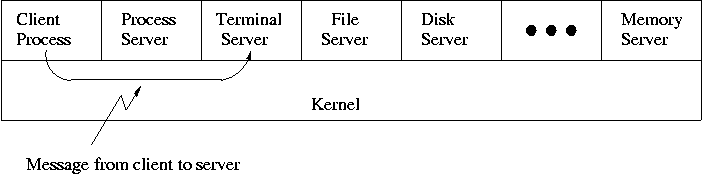

I must note that Tanenbaum is a big advocate of the so called microkernel approach in which as much as possible is moved out of the (supervisor mode) microkernel into separate processes.

In the early 90s this was popular. Digital Unix (now called True64) and Windows NT are examples. Digital Unix is based on Mach, a research OS from Carnegie Mellon university. Lately, the growing popularity of Linux has called into question the belief that ``all new operating systems will be microkernel based''.

The previous picture: one big program

The system switches from user mode to kernel mode during the poof and then back when the OS does a ``return''.

But of course we can structure the system better, which brings us to.

Some systems have more layers and are more strictly structured.

An early layered system was ``THE'' operating system by Dijkstra. The layers were.

The layering was done by convention, i.e. there was no enforcement by hardware and the entire OS is linked together as one program. This is true of many modern OS systems as well (e.g., linux).

The multics system was layered in a more formal manner. The hardware provided several protection layers and the OS used them. That is, arbitrary code could not jump to or access data in a more protected layer.

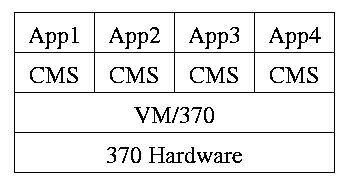

Use a ``hypervisor'' (beyond supervisor, i.e. beyond a normal OS) to switch between multiple Operating Systems. Made popular by IBM's VM/CMS

Similar to VM/CMS but the virtual machines have disjoint resources (e.g., distinct disk blocks) so less remapping is needed.

When implemented on one computer, a client server OS is using the microkernel approach in which the microkernel just supplies interprocess communication and the main OS functions are provided by a number of separate processes.

This does have advantages. For example an error in the file server cannot corrupt memory in the process server. This makes errors easier to track down.

But it does mean that when a (real) user process makes a system call there are more processes switches. These are not free.

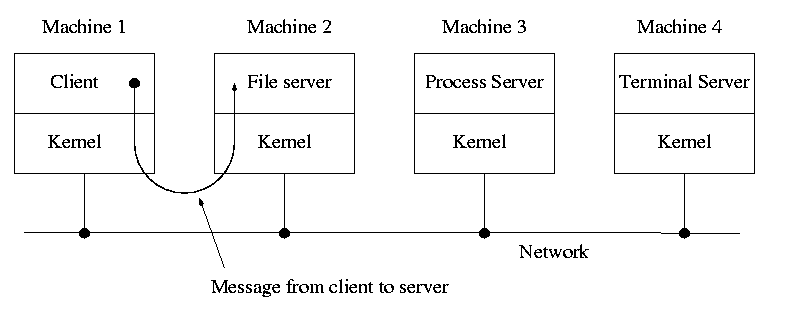

A distributed system can be thought of as an extension of the client server concept where the servers are remote.

Homework: 23