================ Start Lecture #23

================

RAID (Redundant Array of Inexpensive Disks)

- Tanenbaum's treatment is not very good.

- The name RAID is from Berkeley.

- IBM changed the name to Redundant Array of Independent

Disks. I wonder why?

- A simple form is mirroring, where two disks contain the

same data.

- Another simple form is striping (interleaving) where consecutive

blocks are spread across multiple disks. This helps bandwidth, but is

not redundant. Thus it shouldn't be called RAID, but it sometimes is.

- One of the normal RAID methods is to have N (say 4) data disks and one

parity disk. Data is striped across the data disks and the bitwise

parity of these sectors is written in the corresponding sector of the

parity disk.

- On a read if the block is bad (e.g., if the entire disk is bad or

even missing), the system automatically reads the other blocks in the

stripe and the parity block in the stripe. Then the missing block is

just the bitwise exclusive or of all these blocks.

- For reads this is very good. The failure free case has no penalty

(beyond the space overhead of the parity disk). The error case

requires N+1 (say 5) reads.

- A serious concern is the small write problem. Writing a sector

requires 4 I/O. Read the old data sector, compute the change, read

the parity, compute the new parity, write the new parity and the new

data sector. Hence one sector I/O became 4, which is a 300% penalty.

- Writing a full stripe is not bad. Compute the parity of the N

(say 4) data sectors to be written and then write the data sectors and

the parity sector. Thus 4 sector I/Os become 5, which is only a 25%

penalty and is smaller for larger N, i.e., larger stripes.

- A variation is to rotate the parity. That is, for some stripes

disk 1 has the parity, for others disk 2, etc. The purpose is to not

have a single parity disk since that disk is needed for all small

writes and could become a point of contention.

5.3.3: Error Handling

Disks error rates have dropped in recent years. Moreover, bad

block forwarding is done by the controller (or disk electronic) so

this topic is no longer as important for OS.

5.3.4: Track Caching

Often the disk/controller caches a track, since the

seek penalty has already been paid. In fact modern disks have

megabyte caches that hold recently read blocks. Since modern disks

cheat and don't have the same number of blocks on each track, it is

better for the disk electronics (and not the OS or controller) to do

the caching since it is the only part of the system to know the true

geometry.

5.3.5: Ram Disks

- Fairly clear. Organize a region of memory as a set of blocks and

pretend it is a disk.

- A problem is that memory is volatile.

- Often used during OS installation, before disk drivers are

available (there are many types of disk but all memory looks

the same so only one ram disk driver is needed).

5.4: Clocks

Also called timers.

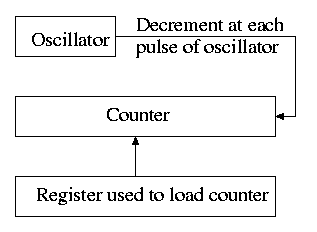

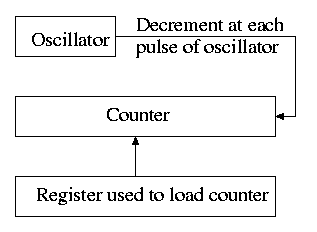

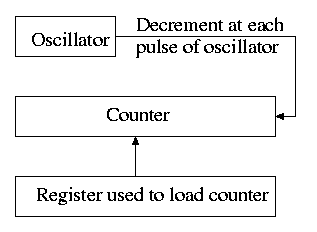

5.4.1: Clock Hardware

- Generates an interrupt when timer goes to zero

- Counter reload can be automatic or under software (OS) control.

- If done automatically, the interrupt occurs periodically and thus

is perfect for generating a clock interrupt at a fixed period.

5.4.2: Clock Software

- TOD: Bump a counter each tick (clock interupt). If counter is

only 32 bits must worry about overflow so keep two counters: low order

and high order.

- Time quantum for RR: Decrement a counter at each tick. The quantum

expires when counter is zero. Load this counter when the scheduler

runs a process.

- Accounting: At each tick, bump a counter in the process table

entry for the currently running process.

- Alarm system call and system alarms:

- Users can request an alarm at some future time.

- The system also on occasion needs to schedule some of its own

activities to occur at specific times in the future (e.g. turn off

the floppy motor).

- The conceptually simplest solution is to have one timer for

each event.

- Instead, we simulate many timers with just one.

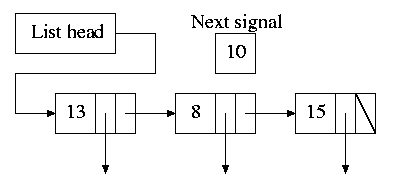

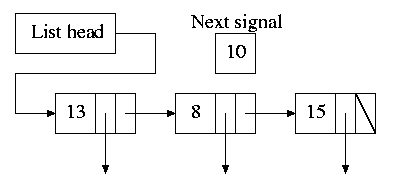

- The data structure on the right works well.

- The time in each list entry is the time after the

preceding entry that this entry's alarm is to ring.

- For example, if the time is zero, this event occurs at the

same time as the previous event.

- The other entry is a pointer to the action to perform.

- At each tick, decrement next-signal.

- When next-signal goes to zero,

process the first entry on the list and any others following

immediately after with a time of zero (which means they are to be

simultaneous with this alarm). Then set next-signal to the value

in the next alarm.

- Profiling

- Want a histogram giving how much time was spent in each 1KB

(say) block of code.

- At each tick check the PC and bump the appropriate counter.

- A user-mode program can determine the software module

associated with each 1K block.

- If we use finer granularity (say 10B instead of 1KB), we get

increased accuracy but more memory overhead.

Homework: 12

5.5: Terminals

5.5.1: Terminal Hardware

Quite dated. It is true that modern systems can communicate to a

hardwired ascii terminal, but most don't. Serial ports are used, but

they are normally connected to modems and then some protocol (SLIP,

PPP) is used not just a stream of ascii characters. So skip this

section.

5.5.2: Memory-Mapped Terminals

Not as dated as the previous section but it still discusses the

character not graphics interface.

- Today, software writes into video memory

the bits that are to be put on the screen and then the graphics

controller

converts these bits to analog signals for the monitor (actually laptop

displays and some modern monitors are digital).

- But it is much more complicated than this. The graphics

controllers can do a great deal of video themselves (like filling).

- This is a subject that would take many lectures to do well.

- I believe some of this is covered in 201.

Keyboards

Tanenbaum description of keyboards is correct.

- At each key press and key release a code is written into the

keyboard controller and the computer is interrupted.

- By remembering which keys have been depressed and not released

the software can determine Cntl-A, Shift-B, etc.

5.5.3: Input Software

- We are just looking at keyboard input. Once again graphics is too

involved to be treated here.

- There are two fundamental modes of input, sometimes called

raw and cooked.

- In raw mode the application sees every ``character'' the user

types. Indeed, raw mode is character oriented.

- All the OS does is convert the keyboard ``scan codes'' to

``characters'' and and pass these characters to the application.

- Some examples

- down-cntl down-x up-x up-cntl is converted to cntl-x

- down-cntl up-cntl down-x up-x is converted to x

- down-cntl down-x up-cntl up-x is converted to cntl-x (I just

tried it to be sure).

- down-x down-cntl up-x up-cntl is converted to x

- Full screen editors use this mode.

- Cooked mode is line oriented. The OS delivers lines to the

application program.

- Special characters are interpreted as editing characters

(erase-previous-character, erase-previous-word, kill-line, etc).

- Erased characters are not seen by the application but are

erased by the keyboard driver.

- Need an escape character so that the editing characters can be

passed to the application if desired.

- The cooked characters must be echoed (what should one do if the

application is also generating output at this time?)

- The (possibly cooked) characters must be buffered until the

application issues a read (and an end-of-line EOL has been received

for cooked mode).

5.5.4: Output Software

Again too dated and the truth is too complicated to deal with in a

few minutes.

Homework: 16.