==== Start Lecture #13

====

5.5.3: Input Software

- We are just looking at keyboard input. Once again graphics is too

involved to be treated here.

- Two fundamental modes of input raw and cooked.

- In raw mode the application sees every ``character'' the user

types. Indeed, raw mode is character oriented.

- All the OS does is convert the keyboard ``scan codes'' to

``characters'' and and pass these characters to the application.

to w

- Some examples

- down-cntl down-x up-x up-cntl is converted to cntl-x

- down-cntl up-cntl down-x up-x is converted to nothing

- down-cntl down-x up-cntl up-x is converted to cntl-x (I just

tried it to be sure).

- down-x down-cntl up-x up-cntl is converted to x

- Full screen editors use this mode.

- Cooked mode is line oriented. The OS delivers lines to the

application program.

- Erased characters are not seen by the application but are

erased by the keyboard driver.

- Special characters are interpreted as editing characters

(erase-previous-character, erase-previous-word, kill-line, etc).

- Need an escape character so that the editing characters can be

passed to the application if desired.

- The cooked characters must be echoed (what should one do if the

application is also generating output at this time?)

- The (possibly cooked) characters must be buffered until the

application issues a read (and an end-of-line EOL has been received

for cooked mode).

5.5.4: Output Software

Again too dated and the truth is too complicated to deal with in a

few minutes.

Homework: 16.

Chapter 6: Deadlocks

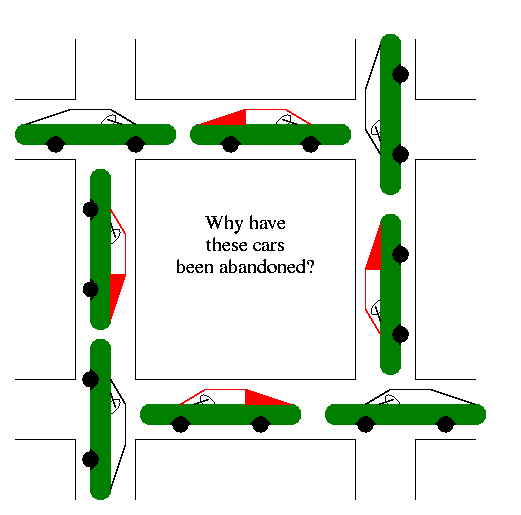

A deadlock occurs when a every member of a set of

processes is waiting for an event that can only be caused

by a member of the set. Often the event waited for is the release of

a resource.

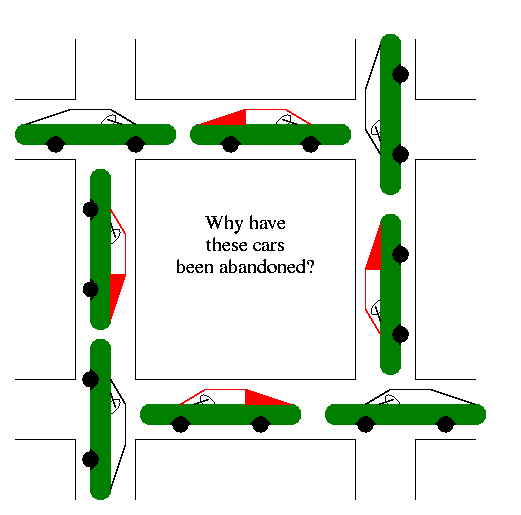

In the automotive world deadlocks are called gridlocks.

- The processes are the cars.

- The resources are the spaces occupied by the cars

Reward: One point extra credit on the final exam

for anyone who brings a real (e.g., newspaper) picture of an

automotive deadlock. You must bring the clipping to the final and it

must be in good condition. Hand it in with your exam paper.

For a computer science example consider two processes A and B that

each want to print a file currently on tape.

- A has obtained ownership of the printer (but will release it when it

finished printing).

- B has obtained ownership of the tape drive (but will release when

it has finished reading the tape).

- A tries to get ownership of the tape drive, but is told to wait

for B to release it.

- B reads a block from the tape and then tries to get ownership of

the printer to print the block; naturally B is told to wait for A to

release the printer.

Bingo: deadlock!

6.1: Resources:

The resource is the object granted to a process.

- Resources come in two types

- Preemptable, meaning that the resource can be

taken away from its current owner. An example is memory.

- Non-preemptable, meaning that the resource

cannot be taken away. An example is a printer.

- The interesting issues arise with non-preemptable resources so

those are the ones we study.

- Life history of a resource is a sequence of

- Request

- Allocate

- Use

- Release

- Processes make requests, use the resourse, and release the

resourse. The allocate decisions are made by the system and we will

study some policies used to make these deci

6.2: Deadlocks

To repeat: A deadlock occurs when a every member of a set of

processes is waiting for an event that can only be caused

by a member of the set. Often the event waited for is the release of

a resource.

6.3: Necessary conditions for deadlock

The following four conditions (Coffman; Havender) are

necessary but not sufficient for deadlock. Repeat:

They are not sufficient.

- Mutual exclusion: A resource can be assigned to at most one

process at a time (no sharing).

- Hold and wait: A processing holding a resource is permitted to

request another.

- No preemption: A process must release its resources; they cannot

be taken away.

- Circular wait: There must be a chain of processes such that each

member of the chain is waiting for a resource held by the next member

of the chain.

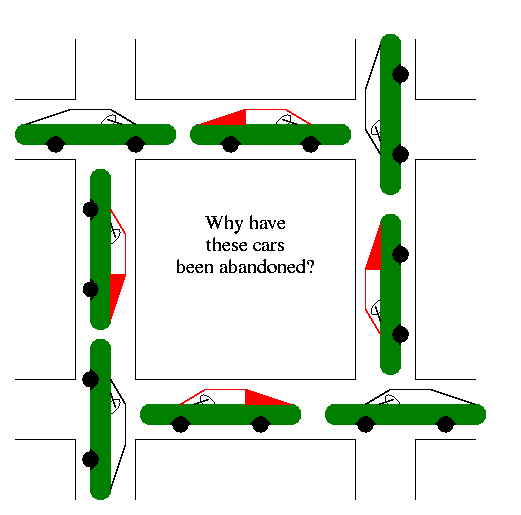

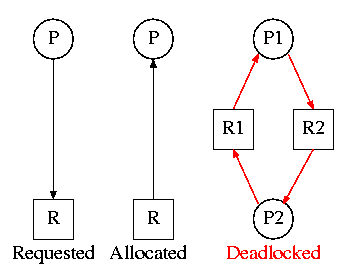

6.2.2: Deadlock Modeling

On the right is the Resource Allocation Graph,

also called the Resourse Graph.

- The processes are circles.

- The resourses are squares.

- An arc (directed line) from a process P to a resourse R signifies

that process P has requested (but not yet been allocated) resourse R.

- An arc from a resourse R to a process P indicates that process P

has been allocated resource R.

Homework: 1.

Consider two concurrent processes P1 and P2 whose programs are.

P1: request R1 P2: request R2

request R2 request R1

release R2 release R1

release R1 release R2

On the board draw the resource allocation graph for various possible

executions of the processes, indicating when deadlock occurs and when

deadlock is no longer avoidable.

There are four strategies used for dealing with deadlocks.

- Ignore the problem

- Detect deadlocks and recover from them

- Avoid deadlocks by carefully deciding when to allocate resources.

- Prevent deadlocks by violating one of the 4 necessary conditions.

6.3: Ignoring the problem--The Ostrich Algorithm

The ``put your head in the sand approach''.

- If the likelihood of a deadlock is sufficiently small and the cost

of avoiding a deadlock is sufficiently high it might be better to

ignore the problem. For example if each PC deadlocks once per 100

years, the one reboot may be less painful that the restrictions needed

to prevent it.

- Clearly not a good philosophy for nuclear missile launchers.

- For embedded systems (e.g., missile launchers) the programs run

are fixed in advance so many of the questions tannenbaum raises (such

as many processes wanting to fork at the same time) don't occur.

6.4: Detecting Deadlocks and Recovering from them

6.4.1: Detecting Deadlocks with single unit resources

Consider the case in which there is only one instance of each

resource.

- So a request can be satisfied by only one specific resourse.

- In this case the 4 necessary conditions for deadlock are also

sufficient.

- Remember we are making an assumption (single unit resources) that

is often invalid. For example, many systems have several printers and

a request is given for ``a printer'' not a specific printer.

Similarly, one can have many tape drives.

- So the problem comes down to finding a directed cycle in the resource

allocation graph. Why?

Ans: Because the other three conditions are either satisfied by the

system we are studying or are not in which case deadlock is not a

question. That is, conditions 1,2,3 are contitions on the system in

general not on what is happening right now.

To find a directed in a directed graph is not hard. The algorithm

is in the book. The idea is simple.

- For each node in the graph do a depth first traversal (hoping the

graph is a DAG (directed acyclic graph), building a list as you go

down the DAG.

- If you ever find the same node twice on your list, you have found

a directed cycle and the graph is not a DAG and deadlock exists among

the processes in your current list.

- If you never find the same node twice, the graph is a DAG and no

deadlock occurs.

- The searches are finite since the list size is bounded by the

number of nodes.

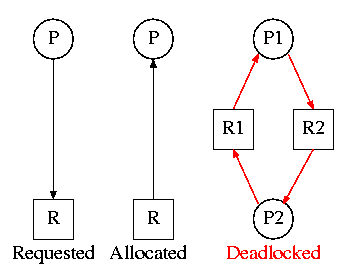

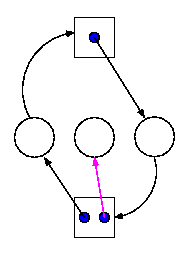

6.4.2: Detecting Deadlocks with multiple unit resources

This is more difficult.

- The figure on the right shows a resource allocation graph with

multiple unit resources.

- Each unit is represented by a dot in the box.

- Request edges are drawn to the box since they represent a request

for any dot in the box.

- Allocation edges are drawn from the dot to represent that this

unit of the resource has been assigned (but all units of a resource

are equivalent and the choice of which one to assign is arbitrary).

- Note that there is a directed cycle in black, but there is no

deadlock. Indeed the middle process might finish, erasing the magenta

arc and satisfying the process on the right.

- The book gives an algorithm for detecting deadlocks in this more

general setting. The idea is as follows.

- look for process that might be able to terminate (i.e. all its

request arcs can be satisfied).

- If one is found pretend that it does terminate (erase all its

arcs) and repeat step 1.

- If any processes remain, they are deadlocked.

- We will really do an algorithm later (the Banker's algorithm) that

has some of this flavor.

6.4.3: Recovery from deadlock

Preemption

Perhaps you can temporarily preempt a process. Not likely.

Rollback

Database (and other) systems take periodic checkpoints. If the

system does take checkpoints, one could roll back to one.

Kill processes

Can always be done but might be painful. For example some

processes have had effects that can't be simply undone. Print, launch

a missle, etc.

6.5: Deadlock Avoidance

Let's see if we can tiptoe through the tulips and avoid deadlock

states even though our system does permit all four of the necessary

conditions for deadlock.

An optimistic resource manager is one that grants every

request as soon as it can. To avoid deadlocks with all four

conditions present, the manager must be smart not optimistic.

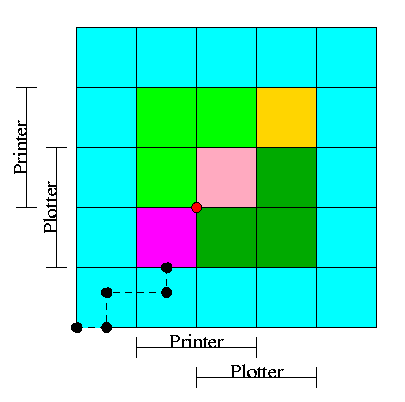

6.5.1 Resource Trajectories

I believe this is a tannenbaumism. I have never tried to teach it

before but the possibility of color might make this understandable.

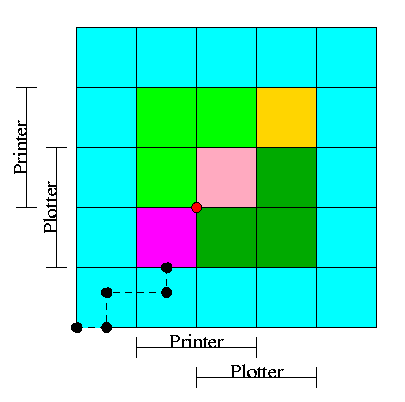

- We have two processes H (horizontal) and V.

- The origin represents them both starting.

- Their combined state is a point on the graph.

- The parts where the printer and plotter are needed by each process

are indicated.

- The dark green is where both processes have the plotter and hence

execution cannot reach this point.

- Light green represents both having the printer; also impossible.

- Pink is both having both printer and plotter; impossible.

- Gold is possible (H has plotter, V has printer), but you can't get

there.

- The upper right corner is the goal both processes finished.

- The red dot is ... (cymbals) deadlock. We don't want to go there.

- The cyan is safe. From anywhere in the cyan we have horizontal

and vertical moves to the finish line without hitting any impossible

area.

- The magenta interior is very interesting. It is

- Possible: each processor has a different resource

- Not deadlocked: each processor can move within the magenta

- Deadly: deadlock is unavoidable. You will hit a magenta-green

boundrary and then will no choice but to turn and go to the red dot.

- The cyan-magenta border is the danger zone

- The dashed line represents a possible execution pattern.

- With a uniprocessor no diagonals are possible. We either move to

the right meaning H is executing or move up indicating V.

- The trajectory shown represents.

- H excuting a little

- V excuting a little

- H executes; requests the printer; gets it; executes some more

- V executes; requests the plotter

- The crisis is at hand!

- If the resource manager gives V the plotter, the magenta has been

entered and all is lost. ``Abandon all hope yee who enter here''

--dante.

- The right thing to do is to deny the request, let H execute moving

horizontally under the magenta and dark green. At the end of the dark

green, no danger remains, both processes will terminate.