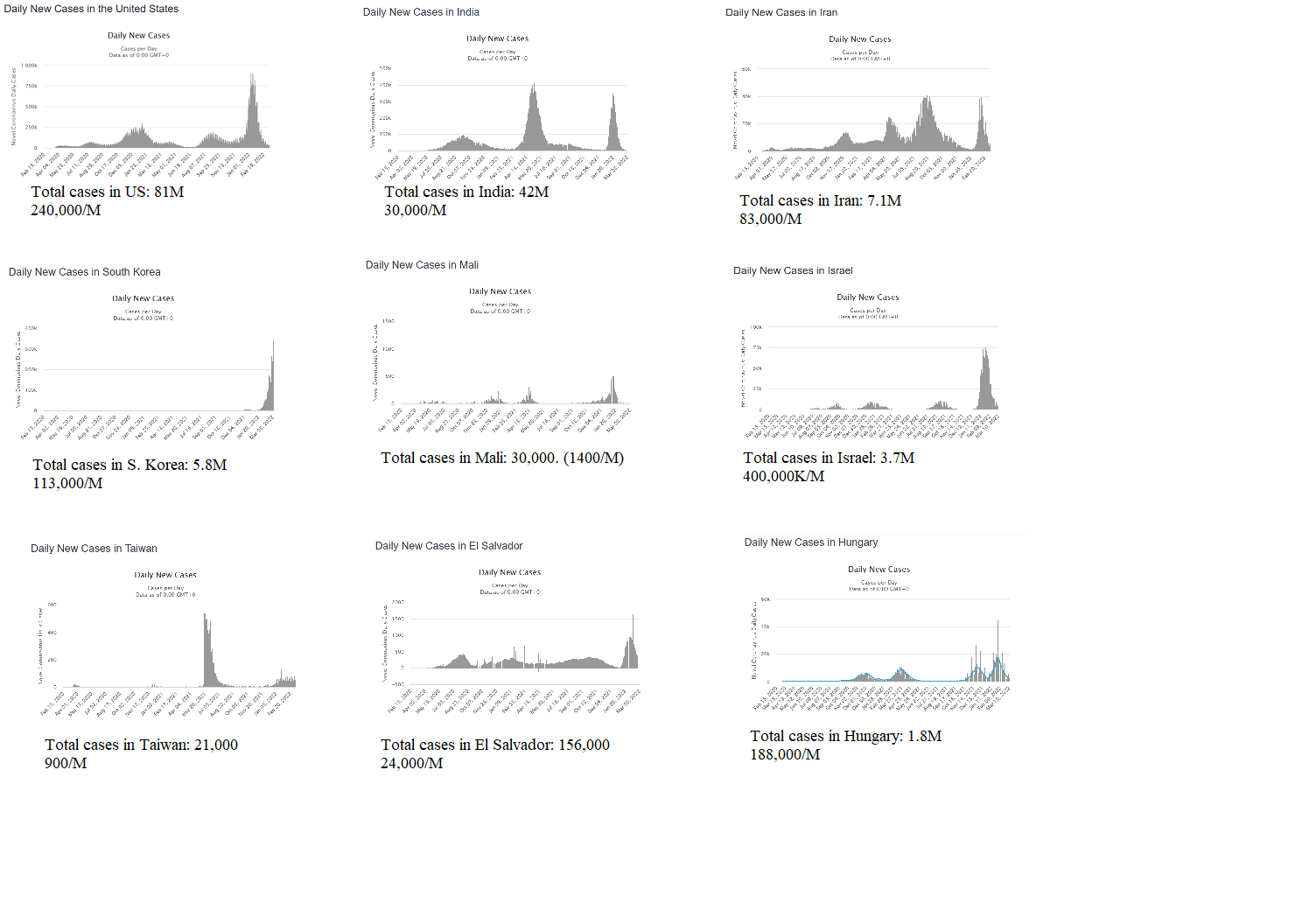

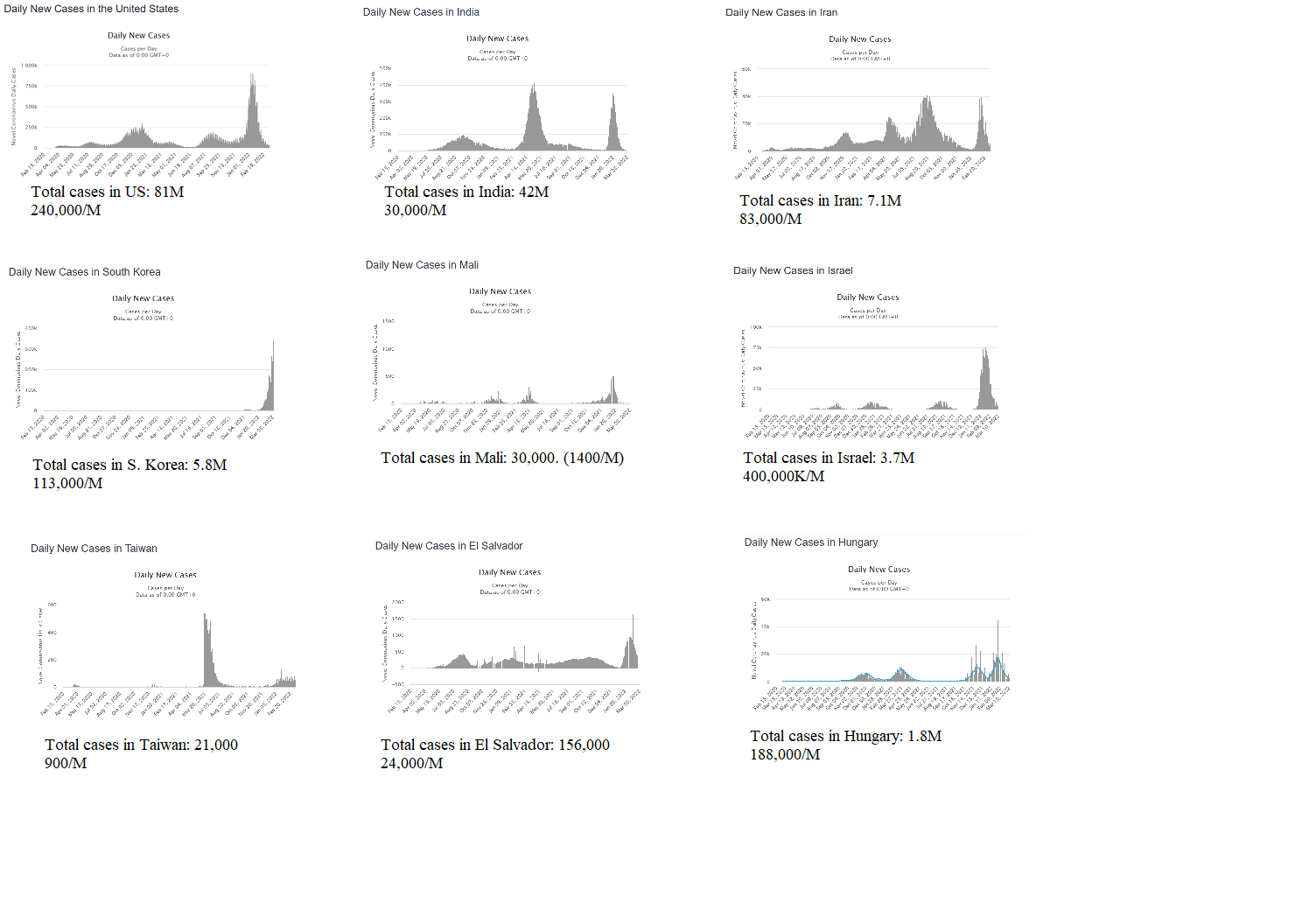

The diagram below shows "New Cases per Day" for nine different countries. (The data is taken from http://worldometers.info/covid. Please note that the scales of the y-axes are all different.)

Of course, this data is not nearly of the quality that one would want; the collection methods vary widely, both across countries and across time. No doubt all of these numbers are underestimates, and some are probably much worse than others. Still, I think that one can safely conclude that these are different, even without doing a statistical analysis (and I have to admit I have no idea what kind of statistical measure would be the right one.) They are also very different from the bell curves that were predicted in March 2020.

The question is, why are they so different? I presume that epidemiologists have been working hard on that question, and one might suppose that, two years into the pandemic, they would by this time have some pretty clear answers. But if the answers are known, I certainly haven't seen them.

I can imagine an answer along any of the following lines:

It may well be that cross-country comparisons is too coarse a scale, but that one can give an explanation of this kind if you do a more fine-grained comparison. The US and India are merely sums of significantly different curves in different areas or subpopulations.

What I'm looking for, in short, is a history of the pandemic, that uses perfect 20/20 hindsight to explain the broad aspects of its spread over time. Either that, or an explanation of why no such history is feasible.

If indeed no such history is feasible, for reason (2) or (3), then what does that imply for epidemiological modeling, prediction, and control? Do epidemiologists find this kind of variance surprising, or is it pretty much to be expected from a global pandemic?

I think most people would agree that, as argued by Zeynep Tufekci, the actions by governments and by the public were often unwise, and that wiser policy and behavior could have reduced the number of cases significantly and the number of deaths even more significantly. But I am doubtful that one can quantify that hypothetical impact with any kind of precision, perhaps not even within an order of magnitude.

Particularly discouraging in that regard are cases like South Korea, Japan, and New Zealand, which had great success from early in the pandemic for almost two years, until January 2022 when whatever had been working suddenly stopped working, and the number of cases exploded (though the number of deaths remains much smaller than the US or Europe). Presumably at this point these governments and societies knew much more than anyone could possibly have known in March 2020 and had tools (particularly vaccination) that did not exist in March 2020, and presumably the number of cases in those countries on January 1, 2022 was tiny, but still they could not prevent the disease from taking off. At this point the only large countries that have really been successful from near the start to finish have been China, which imposed truly Draconian measures, Taiwan, and some of the African countries (again, for reasons largely unexplained).