Remembrances of Jack

Michael Schwartzman

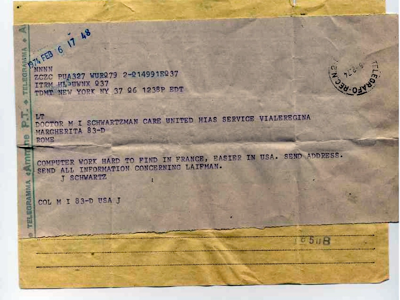

“Computer work hard to find in France, easier in USA STOP Send address STOP Send all information concerning Laifman STOP Jack Schwartz”

Thus begun a journey of deep friendship that was more flawless that any friendship I ever had.

I received this telegram in Rome, in a refugee dormitory on February 6, 1974, I was 28 and Jack was 45. I have the original telegram with me, here (attached).

I am Michael Schwartzman. I am the Managing Partner of ValueSearch Capital Management in Massachusetts. I was a computer scientist for 20 years and an investments manager for the last 20 years.

Dr. Laifman, a scientist who worked with me and who was stuck in the Soviet Union harassed by the authorities, is also mentioned in this telegram. He later arrived to the United States, probably with Jack’s help -- Laifman died many years ago -- we will never know.

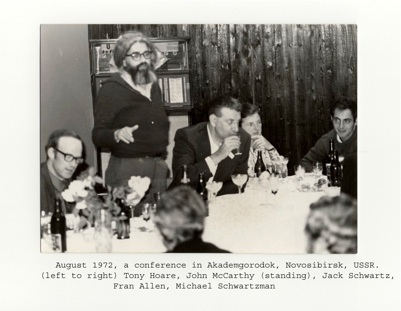

There were many things that hardly anyone knew about Jack --I kept it a tight secret until well after the perestroika: Jack helping me, our secret rendezvous in my Siberian apartment with Ukrainian songs blasting loudly from a record player to fool the possible surveillance by KGB (Ukrainian, because my physicists friends thought the frequencies were the best to defeat the wiretapping), and our coded signals half of which Jack forgot by the time he got back to the United States and yet by luck and by my quick thinking, they worked -- better than expected. I can tell you about this more during the reception.

There is no single person in the United States to whom I owe more than to Jack. Three years ago, when I became more and more aware of my and Jack’s mortality, I sent him my just finished essay about Academician Ershov, my mentor in the Soviet Union and Jack’s colleague, with this inscription:

“You graced me with your help, support, friendship, forgiveness of my occasional mistakes, and tolerance of my faults. I am eternally in debt to you. I am glad that writing about Ershov’s legacy also turned into a chance to tell you how grateful I am for the help you gave me long time ago”.

I did get a response, “ Dear Michael, Thank you for your very kind words about the modest help I provided”, followed by a page of discussion related to proof verification, visual psycho-physics, middle school mathematics -- and a bit about Jack’s cancer…

I can tell you more about Jack and me fooling KGB later, if the time allows, or at the reception. Now I want to tell you about a phenomenon that puzzled me my entire life and if I learned anything about it, it’s only because I have lived long enough, it is not something we know when we are young.

Keeping a friendship with a former benefactor is fraught with risk of failure, failure of friendship, failure of warmth, failure of hope. Jack and I kept the friendship.

The continuation of friendship between a benefactor and a beneficiary requires utmost skill and talent from both. Jack had it all, and I brought to this relationship my not yet perfect skill. I know, I am a benefactor to many, I have helped many as significantly as Jack helped me: to escape the Soviet Union, or to come to the US from Israel, or from refugee camps in Italy -- and have a job and apartment waiting. Not all of my charity resulted in enduring friendships -- it even wrecked a friendship or two. Jack had it right; he had a perfect intuition and a good mind about handling these often treacherous waters.

When my wife and our 5 year old son arrived 35 years ago we were perfect greenhorns from a distant and different world. We lived for the first month in the Riverside Drive apartment, where Jack, Fran Allen and the girls lived. I still think that we provided Abby and Rachel, teenagers then, with a lifetime of chuckles at our greenhorns’ mistakes, for example, not knowing how to eat a grapefruit, a fruit we have never seen in Russia. I think, in exchange, when I asked them how to spell my son’s name in the about to be issued Social Security card, the girls have chosen the spelling that was, to say the least, unusual, and he is still stuck with it.

Jack always made me feel equal in all respects and would break the tension of a misunderstanding by, as it once happened, discussing with me at length the infinite possibilities that would have arisen had he married Svetlana Allilueva, Stalin’s daughter, to whom Jack was introduced several years earlier when she was making rounds among the New York glitterati – the possibilities were mind boggling to both of us: Jack could have become a son-in-law to the world’s worst butcher…

The strong and quiet friendship we enjoyed was a friendship born of understanding and hope that the other one knows -- it took me 30 years to write Jack the letter I quoted above (well, minus 15 years because of the secrecy I was preserving to keep KGB in dark and not invite its interference with Jack’s travel to the USSR). Jack never told me that he was proud of the achievements of the compiler development company that I had founded, and that he thought I was a very good money manager – he told this to Diana, and she told me about this only recently. And yet I knew how welcome I was, and I rarely skipped a visit to Jack whenever I was on business in New York.

It was indeed a friendship of little advice from Jack, in fact I remember no unsolicited advice ever given – and if one was given, it would have been, probably, to write shorter speeches…

Our friendship was one of little small talk, thus Jack never knew that my computer science friends in Massachusetts have compiled a tree of connections starting with me and those who I helped to move to the United States, and those who they helped, and on and on – the tree apparently contains several hundred people of whom I know only the top level.

Because of the secrecy that I maintained, hardly anyone knows that Jack is at the very top of that tree, and that several hundred people are eternally in debt to him, as I am.

Thank you, Jack.

Friday, March 27, 2009